Trade, Ships, and Whiskey:

Gooderham and Worts' Operations and Effect on The Port of Toronto

Samuel McDonald

Toronto - 2023

The culture of the Great Lakes is inextricably interlinked with the practice of maritime trade, due to the fact that a large percentage of the region is composed of water and coastal cities. As a consequence of this, the manner in which society surrounding the Great Lakes has developed throughout time cannot be separated from the influence of trade and shipping. The materials imported to and exported from the area and the employment opportunities that the industry provided for the region’s citizens are just a few of the major ways in which shipping and trade have impacted the Great Lakes region’s development, and more specifically that of the Port of Toronto.

In order to contextualize the importance of maritime trade within the Great Lakes region, this essay will examine the water-based operations of an alcohol distillery, Gooderham and Worts (G&W), which operated out of Toronto through the 19th and 20th centuries after its foundation in 1831.1 Through the analysis of the day-to-day operations and shipping practices of the company, their management of various shipping risks, and the employment of their various ships, the rise of Gooderham and Worts as a titan in the alcohol industry will be explored. This will serve as a lens through which one can assess the importance of shipping and trade and G&W’s impact on the development of the Great Lakes and the Port of Toronto.

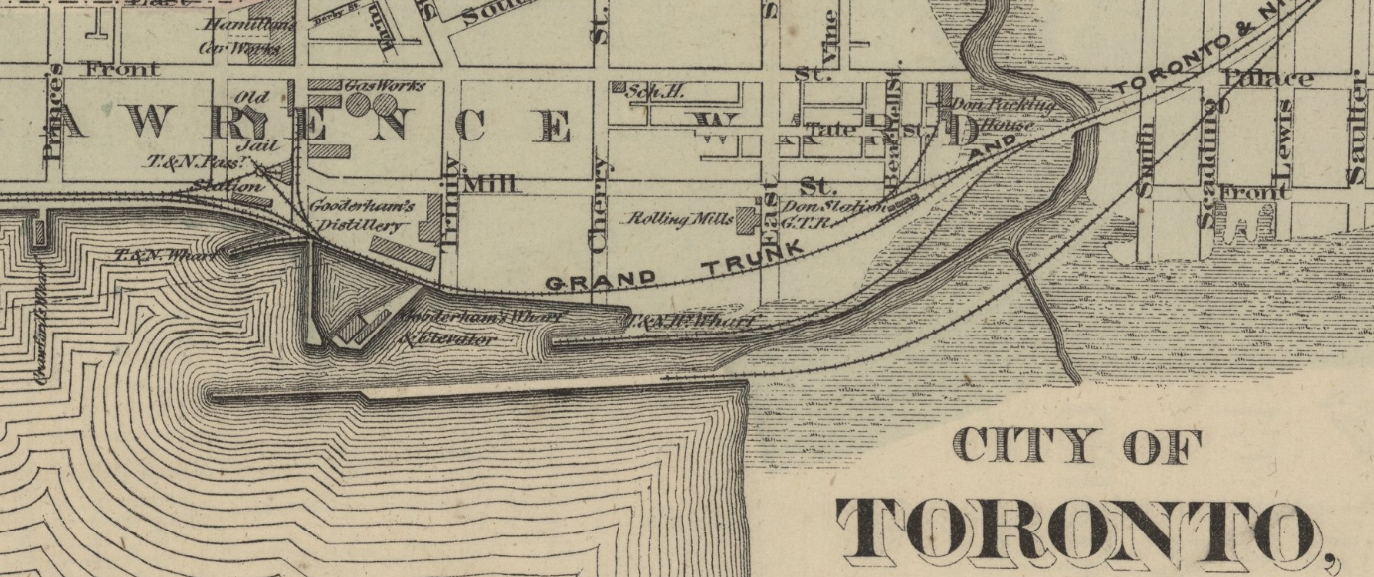

One of the most significant factors of G&W’s shipping operations is the company’s facilities. This study will focus on the facilities located on the Toronto harbour, although there were many other buildings that contributed to the company’s operations as well, such as the mill seen in Figure 1.2 Toronto’s distillery district was composed of dozens of buildings used for the purpose of distilling alcohol, all built by Gooderham and Worts.3 For example, one of the most significant buildings in this district was the grain elevator owned by G&W, which was perhaps the first of its kind in the Toronto area.4 This structure was one of the foremost factors contributing to Gooderham and Worts’ rise to success: it allowed them to store a great deal more grain than they could have otherwise, supporting the massive amounts of imports, both terrestrial and marine, necessary to run a large alcohol distillery. Figure 2 illustrates the Gooderham and Worts district.5 That G&W owned and used an entire district highlights Gooderham and Worts’ profound influence on the city of Toronto, but there are many additional details that further strengthen this idea. Margaret Kohn states that the distillery district, and specifically G&W, provided many jobs to the people of Toronto,6 which further supports the idea that Gooderham and Worts had a significant influence on the city not only through the capital it brought in via trade, but also through its industrial and urban development, as well as the

employment that it provided for many of the area’s citizens.

In fact, not only did G&W help to shape the Port of Toronto through its construction and usage of various facilities on the Port, but it was also the biggest industrial enterprise in Ontario by 1862, showcasing the large economic impact that the company had made by that point. According to contemporary sources, G&W’s facilities and goods in 1861 amounted to approximately \$200,000, which would equate to nearly 7 million Canadian dollars in modern currency.7 Here, one can see that Gooderham and Worts would have been significantly influential economically due to the amount of capital that they possessed. This capital and the resulting influence were due primarily to the fact that alcohol was such an important part of the lives of blue collar workers, who comprised the majority of the population.8 Additionally, according to certain studies, whiskey was often utilized as a sort of currency during cash shortages, and some scholars have stated that the market economy, which is built on trade of commodities such as alcohol, is what promotes the most growth in a society.9 Thus G&W, being one of the largest alcohol producers in North America, would have certainly had a very large impact on the economy. All of this works together to showcase the fact that Gooderham and Worts has influenced the economy and development of Toronto and the surrounding areas, as well as the lives of the population, in a number of ways.

Another crucial aspect of Gooderham and Worts’ trade and shipping operations, and perhaps the one that would have had the largest effects on the surrounding areas, is the company’s imports and exports. As an alcohol distillery, G&W would have required great amounts of different types of grain, namely corn, wheat, barley, and rye, of which hundreds of thousands of bushels were traded within Canada each year.10 G&W would often have imported all these materials to their Toronto port to facilitate the making of their principal product and export, whiskey. In fact, some sources imply that the whiskey from G&W, along with other goods, was exported internationally as far as Great Britain and Australia by ships such as the schooner James G. Worts.11 The widespread importation of G&W’s whisky shows that G&W was a well-trusted organization that had established clientele across the world, not only in the local Great Lakes region. This example illustrates how Gooderham and Worts would have shaped the economy of Toronto through its import and export of goods. This reputation would not have come easily or quickly, however. Having been founded in 1831, there is evidence that it took a considerable amount of time for G&W to acquire the aforementioned level of influence, as in the year 1850, only approximately 900 gallons of whiskey were exported from all of Canada, including all of the other sources of whiskey.12 This is a marked contrast to sources from a few years later in 1856, where it was stated that G&W alone produced 800 gallons of whiskey per day.13 This implies that the rise of G&W as a major economic player may have taken place in between these years, in the mid 1850s. Regardless of when the rapid growth occurred, however, it is clear that the company established themselves as trustworthy during a time where shipwrecks and other challenges were all too common.

There were several risks facing shipowners and traders in the 19th and 20th centuries, including insurance cost fluctuations, crop yields, and the potential for shipwrecks. In terms of the former, it was common for shipowners who allowed their vessels to deteriorate to be charged, resulting in a fine and likely a loss in reputation.14 For Gooderham and Worts to maintain a sterling reputation and grow their influence, they would have needed to comply with the insurance inspections in their rising years to create an appearance that their vessels were trustworthy. In regard to the challenge of crop yields, sometimes a season would produce an underwhelming amount of grain for import, as was the case in 1904.15 G&W would have been able to work around this issue as well: their aforementioned grain elevator would have allowed them to store large amounts of grain from previous seasons in case of an underwhelming yield, as the crop can last 6 to 12 months in a grain elevator.16 Through both of these examples, one can see how Gooderham and Worts would have been able to circumvent many of the issues of the day that may have impeded their growth as a company. In regard to the final challenge, the potential of shipwrecks, there were several factors influencing the chance of a loss of ship or cargo, including human error, weather conditions, and faulty equipment.17 Gooderham and Worts, like any other shipowner, sometimes fell prey to shipwrecks, but managed to remain an influential company, nonetheless. To fully understand the operations of G&W, one would need to analyze specific examples of ships utilized by the company to contextualize the distillery’s usage of ships in the broader context of shipping and trade.

This paper will examine several of G&W’s ships in terms of their usage, their origins, and their eventual fates, and will analyze their cargo and its importance. See Figure 3 for the locations of the shipwrecks of the four ships that this piece will discuss.18 One such ship was the Minnie Proctor, which ran aground near Oakville in May of 1868 while carrying a cargo of coal for Gooderham and Worts. Luckily, the majority of the cargo and the ship itself were saved with minimal damage.19 This highlights that Gooderham and Worts, like many other large companies in the 19th century, was heavily reliant on coal to fuel their production, which showcases the importance of shipping to maritime culture, as large companies such as G&W would need copious amounts of coal that could be most efficiently delivered to them over the water. Not only does this provide these details regarding the day-to-day operations of the company, but the newspaper article in question also mentions that neither the vessel nor the cargo were insured. This raises some interesting questions regarding the business practices of Gooderham and Worts in the 19th century, particularly if examined in conjunction with the previous analysis of insurance practices. It suggests that large companies such as G&W were willing to cut corners in their day-to-day operations to save money. Despite this possible practice and the losses resulting from it, however, Gooderham and Worts still maintained their status as one of the largest alcohol producers in North America and continued to influence the society of the Great Lakes region and the Port of Toronto.

In addition to the Minnie Proctor, there were several other ships utilized by Gooderham and Worts that are worth examination. The Lottie Wolf, for example, wrecked on a reef near Hope Island while delivering a shipment of corn to Gooderham and Worts in 1891.20 In the same manner as the Minnie Proctor, this showcases how integral shipping and trade was to the operation of Gooderham and Worts, as it provided a way for resources to be quickly transported from the place of their harvest to the facilities where they would be distilled. In addition, this example showcases the connection between different production industries in the 19th century. Specifically, that alcohol production and agriculture were inextricably linked, and that shipping and trade between the two were vital for maintaining and advancing society. Corn was not the only cargo that showcases this connection, however. Other vessels often carried wheat, barley, rye, and flour to and from G&W, and of course the alcohol produced at the company’s facilities was traded as well. For example, the schooner Jacques Cartier was lost near Colborne in 1853 while carrying a large load of flour owned by Gooderham and Worts.21 This again showcases how Gooderham and Worts, and by extension the alcohol distillery industry, was dependant on agriculture, which in turn provides context regarding the importance of shipping and trade for the functioning of society. However, this example also raises an interesting point in contrast to that raised by the case of the Minnie Proctor. In the case of the Jacques Cartier, both ship and cargo were insured, unlike the Minnie Proctor. Since the former wrecked several years earlier than the latter, it raises an interesting idea regarding the growth of Gooderham and Worts and how that may have affected their business practices. As previously mentioned, evidence suggests that the exponential growth of G&W occurred in the mid 1850s, after the wreck of the Minnie Proctor but before that of the Jacques Cartier. Perhaps as the company grew, it became better able to survive financial losses through shipwrecks, and thus its executives may have decided that it would make more financial sense to save money on insurance rather than spending a sum of money up front on the small risk that a ship would wreck. While this is speculation drawn from two case studies, it is an interesting idea that may provide insight into the possible workings of Gooderham and Worts as a company.

The final ship that will be examined in this piece is the James G. Worts (See Figure 4).22 This ship was carrying a large cargo of wheat when it wrecked in 1947 on the Devil’s Shoals in Georgian Bay. However, while the ship was originally owned by Gooderham and Worts, it was no longer under their ownership when it was wrecked.23 Another aspect of the day-to-day workings of Gooderham and Worts was the sale of some of their vessels as they grew, perhaps due to advancements in ship-making rendering them less than optimally efficient, or perhaps because it would make more financial sense to sell certain ships for a large sum of capital rather than to use them for trading purposes. All of the aforementioned examples of trading and shipping vessels, while providing multiple different insights and possibilities, do work together towards a common goal of this examination: they aid with producing a complete understanding of the day-to-day operations of Gooderham and Worts, including the types of vessels used and their fates, the types and amounts of resources needed on a regular basis, and certain financial practices (See Figure 5).24 These understandings are essential for analyzing how G&W contributed to the development of the Great Lakes region and the Port of Toronto.

| Ship | Cargo | Year of Shipwreck | Place of Shipwreck |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minnie Proctor | Unknown amount of coal | 1868 | Oakville |

| Lottie Wolf | Unknown amount of corn | 1891 | Hope Island |

| Jacques Cartier | 1900 barrels of flour | 1853 | Colborne |

| James G. Worts | 20,000 bushels of wheat | 1895 | Devil’s Shoals in Georgian Bay |

Figure 5: Various vessels used by G&W, their cargo, and the place and year of their shipwrecks.

Gooderham and Worts utilized trading vessels to deliver and receive the necessary resources to run their distilling process, and to export the alcohol that they produced. The fact that the company was able to build an entire district around their distillery clearly indicates that their methods were successful. For example, it seems as though their financial choices such as choosing to save money on the insurance of some ships and cargo paid off in the long run despite their losses such as the Minnie Proctor. In fact, G&W were so successful that the area around their distilleries and mills was considered the ideal base in Toronto for harbour development, and they were heralded as the ‘core’ of eastern development in the Great Lakes region.25

In conclusion, after examining various facets of Gooderham and Worts, including its day-to-day operations and its impact on the Port of Toronto, it becomes clear that the company was vastly influential to the development of the Port and the surrounding areas. Through this influence, G&W becomes an example of just how important the shipping and trade business was to the development of maritime societies. The company was found to have had dramatic influences on the urban development and economy of Toronto (including the Port) after building an empire through its shipping practices, operations and its risk management strategies, which were examined in detail to provide context using case studies of specific ships. In addition, it was found to have influenced the lives of the people of Toronto through its providing of job opportunities. Overall, through all of these examples, the importance of shipping and trade to maritime societies, specifically the Great Lakes region and the city and Port of Toronto, was demonstrated through the case study of Gooderham and Worts.

-

Author Unknown, The Globe [Toronto], 13 Dec. 1856. http://distilleryheritage.com/PDFs/report4/part1.pdf. ↩

-

Figure 1: A Gooderham and Worts-owned grain mill. Artist Unknown, The Old Gooderham and Worts Mill at the Beginning of the Windmill Line, Crayon Drawing, Maritime History of the Great Lakes, 1835. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/125698/image/169373?n=1. ↩

-

Margaret Kohn, “Toronto's Distillery District: Consumption and Nostalgia in a Post-Industrial Landscape,” Globalizations 7, no. 3 (2010): 360. ↩

-

Sally Gibson, “Ghost Buildings: Grain Elevators,” Distillery Heritage Snippets, (2008): 2. http://www.distilleryheritage.com/snippets/62.pdf. ↩

-

Figure 2: A map showcasing the general area of the Gooderham and Worts distillery district, with the main wharf and distillery circled in red. G.N. Tackabury, City of Toronto, reduced by permission from Wadsworth & Unwin's Large Map for Tackabury's Atlas of the Dominion, Crayon Drawing, York University Digital Library, 1875. https://digital.library.yorku.ca/yul-1153579/city-toronto-reduced-permission-wadsworth-unwins-large-map-tackaburys-atlas-dominion. ↩

-

Margaret Kohn, “Toronto's Distillery District: Consumption and Nostalgia in a Post-Industrial Landscape,” Globalizations 7, no. 3 (2010): 366. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Annual Review of The Trade of Toronto, For 1861: Distillery of Messrs. Gooderham and Worts The Globe (1844-1936); Feb 7, 1862; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Globe and Mail. ↩

-

Jason Russell, “Finding Canada’s History of Capitalism in the Work of Craig Heron,” Left History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Historical Inquiry and Debate 21, no. 1 (2019): 45. https://doi.org/10.25071/1913-9632.39413. ↩

-

Douglas S. Harvey, “Connecting the Dots: The Foundation of American Empire,” Canadian Review of American Studies 49, no. 3 (2019): 396. https://doi.org/10.3138/cras.2017.033; Charles K. Harley, “Shipping, Maritime Trade and the Economic Development of Colonial North America by James F. Shepherd, Garry M. Walton (Review),” The Canadian Historical Review 55, no. 3 (September 1974): 342–43; P. Hincks, “Tables of the Trade and Navigation of the Province of Canada for the Year 1850.” https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/statcan/4-4/CS4-4-1850-eng.pdf. ↩

-

Author Unknown, British Whig (Kingston, ON), Oct. 23, 1882. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/13614/data?n=1; Hincks, “Tables of the Trade and Navigation.” ↩

-

Author Unknown, James G. Worts (Schooner), 1 Aug 1876. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/37735/data?n=1; Author Unknown, The Globe [Toronto], 13 Dec. 1856. http://distilleryheritage.com/PDFs/report4/part1.pdf. ↩

-

Hincks, “Tables of the Trade and Navigation.” ↩

-

Author Unknown. The Globe [Toronto], 13 Dec. 1856. ↩

-

Author Unknown, British Whig (Kingston, ON), 19 Dec 1877. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/73535/data?n=3. ↩

-

Author Unknown, British Whig (Kingston, ON), 10 Aug 1904. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/77165/data?n=1. ↩

-

Ken Wittwer, “Long Term Grain Storage: How Long Can Grains Be Stored? (Wheat, Corn & Quinoa).” Palmetto Industries, March 14, 2022. https://www.palmetto-industries.com/long-term-grain-storage/#:~:text=Typically%2C%20agricultural%20bulk%20grains%20will,monitoring%20and%20proper%20storage%20facilities. ↩

-

Pierre Camu, “Shipwrecks, Collisions and Accidents in St. Lawrence/Great Lakes Waterway, 1848-1900,” The Northern Mariner / Le marin du nord 6, no. 2 (1996): 57. https://doi.org/10.25071/2561-5467.699. ↩

-

Figure 3: Shipwreck locations for the Minnie Proctor (Oakville), the Lottie Wolf (Hope Island), the Jacques Cartier (Colborne), and the James G. Worts (Georgian Bay). Google (2023), Northeastern Great Lakes, Available at https://www.google.com/maps/search/google+maps+lake+ontario+and+erie/@44.0257547,-82.0765182,634192m/data=!3m2!1e3!4b1. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Minnie Proctor (Schooner), aground, 18 May 1868. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/53308/data?n=18. ↩

-

Author Unknown, British Whig (Kingston, ON), 13 Oct 1891. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/74015/data?n=20. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Daily News (Kingston, ON), Nov. 12, 1853. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/16255/data?n=3. ↩

-

Figure 4: The James G. Worts. C.I. Gibbons, The Jas. G. Worts of Toronto, Ont, Crayon Drawing, Maritime History of the Great Lakes, 1947. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/125700/image/169380?n=2. ↩

-

C. H. J. Snider, “End of a Friendship: Schooner Days DCCLXXIX (779),” Toronto Telegram (Toronto, ON), 18 Jan 1947. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/125700/data?n=2. ↩

-

Figure 5: Various vessels used by G&W, their cargo, and the place and year of their shipwrecks. Author Unknown, Minnie Proctor (Schooner), aground, 18 May 1868; Author Unknown, British Whig (Kingston, ON), 13 Oct 1891; Author Unknown, Daily News (Kingston, ON), Nov. 12, 1853; Snider, “End of a Friendship: Schooner Days DCCLXXIX (779).” ↩

-

C. H. J. Snider, “Old Times at the East End of the Bay: Schooner Days DCCLXXVII (777),” Toronto Telegram (Toronto, ON), 4 Jan 1947. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/125698/data?n=1. ↩