Port Towns and Prostitution:

The Social, Moral and Economic Landscape of Buffalo's Canal Street in the 19th Century

Kathryn Cairns

Buffalo - 2025

In the 19th century, Canal Street in Buffalo became known as a vice hotspot primarily for its robust prostitution business. Vice, which was established as activities such as gambling, illegal drinking, sex work, were defined as immoral or unlawful conduct. Canal Street attracted sailors, labourers, and travellers from the booming Port of Buffalo, resulting in a transitory and frequently volatile environment.1 Known for its brothels, saloons and lodging houses, Canal Street benefited from the adjacent Port of Buffalo commercial operations and social events. The Port of Buffalo, located near the western terminus of the Erie Canal, was a crucial hub for business and migration in the 19th century.2 As a Great Lakes port, it permitted shipping key staples such as grain, lumber, and other items vital to regional and national markets. Due to its advantageous location as a hub for economic activity it attracted a temporary, primarily male community of traders, sailors, and dockworkers. This flow of workers and tourists allowed Canal Street's vice businesses such as brothels, saloons and lodgings to gain a stable customer base as they prospered along the waterfront.3 These circumstances, along with the restricted prospects for women in industrializing cities, drove many to prostitution as a way of survival. Reformist groups, such as the Christian Homestead Association, attempted to solve these issues through campaigning, but their attempts were met with established economic interest and systemic injustice.4 Public health worries, notably about the spread of venereal illness, drove municipal officials to set up their regulating efforts, further moulding the legal and moral discourses around the vice on Canal Street.5This essay argues that the 19th century prostitution industry on Buffalo's Canal Street was formed by the port's labour, industrialization, and moral reform attempts, mirroring more considerable contradictions in urban growth and social control. Investigating the economic factors that underlie the vice economy, they move on to the social and gender dynamics that keep it going. The essay will also explore public health problems before delving into legal and moral reform initiatives aimed at changing Canal Street's reputation.

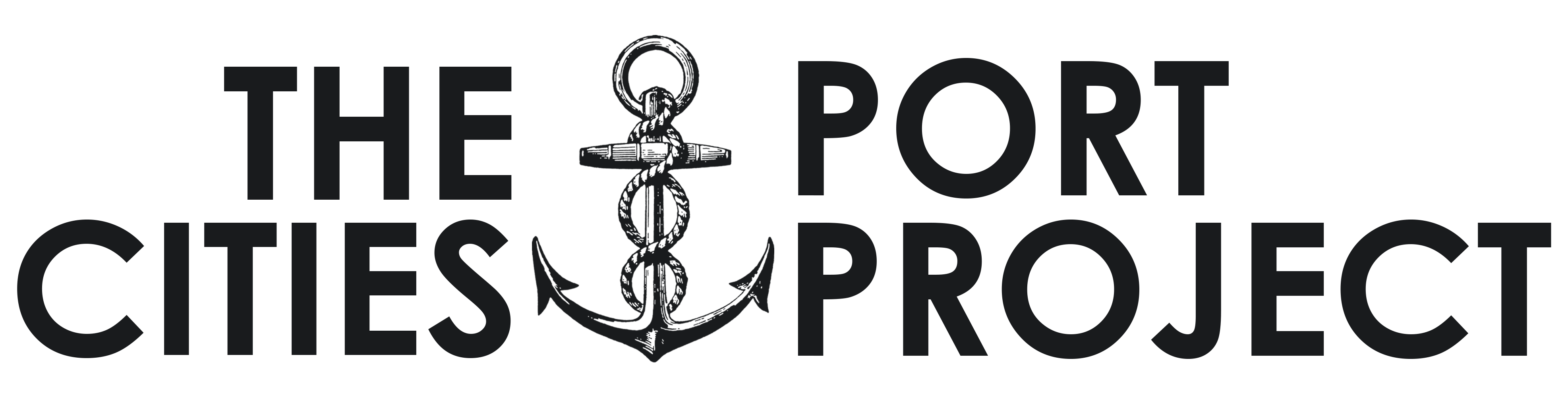

Figure 1: Map of the Retail Places of Business in the District.

Economic Foundation of Vice

Canal Street in Buffalo throughout the 19th century was a prime instance of how industry and urbanization transformed social and economic landscapes; the prostitution industry, was strongly related to the activities of the Port of Buffalo and the intranet workforce it attracted.6 The location of establishments in the port city, including the many saloons and lodging houses, is depicted in Figure 1.7 The port is close to the Erie Canal's western end, serving as a hub for migration and trade, drawing sailors, dockworkers and other temporary workers to the town.8

The port's economic impact went above authorized trade; it fuelled a thriving network of auxiliary enterprises along Canal Street, including brothels, saloons and boarding houses. The map from the New York Heritage Digital Collection shows an abundance of businesses in Buffalo's working-class areas, highlighting how vice sectors were ingrained in the city's economic foundation.9 Industrialization also exacerbated economic inequalities, particularly among women, as there were limited work opportunities and strong societal norms that left women with limited possibilities to make a living. According to historian Marilynn Wood Hill, prostitution frequency became a survival tactic for women experiencing economic exclusion in fast-developing cities.10 The inflow of itinerant workers into the port of Buffalo heightened this dynamic since they had a desire for the prostitution that was established in the town, but the women were afflicted with stigma and risk.11 The vice industry and the port's labour forces had a relationship that worked together; the businesses on Canal Street relied on the support of the dockworkers and sailors that made the neighbourhood economically prosperous. The Port of Buffalo operations and the revolutionary impacts of industrialization were the main economic pillars of the vice on Canal Street.

Figure 2: The Port of Buffalo, the Canal Harbour.

The port workers and the vice industry benefited from each other's labor. Dockworkers and sailors were essential to Canal Street businesses, and their presence boosted the local economy. 12 As seen in Figure 2, the ports served as a nexus for the movement of people and products, supporting the local economy and increasing demand for vice industries. The steady stream of ships brought workers who frequently participated in the events on Canal Street.13 Since many incoming labourers spent their time and money at the town's saloons and brothels, the constant influx of ships into the harbour maintained the thriving vice economy on Canal Street. The public health experts and the moral reformers who advocate for change criticized this reliance, denouncing the vice's negative social and physical effects on working-class people.14

Social and Moral Implications

In addition, through the 19th century, social and moral ramifications of prostitution on Canal Street in Buffalo demonstrated how ethnicity, gender and class interacted to influence the lives of women involved in contentious professions. For economically disadvantaged women, prostitution was essential to their survival but was a more significant social injustice they encountered.15 Economic pressure was the prominent factor that pushed women into prostitution, as the economic changes brought about by industrialization typically excluded women from working-class job opportunities. Many women could not sustain themselves or their families to meet these strict societal standards, so they were restricted to low-paying domestic jobs or positions within factories.16 Marilynn Wood Hill contends that the stigmatization of prostitutes that evolved for women, shut out other acceptable career paths. Many women had to resort to prostitution in cities like Buffalo to escape poverty or lack of social support because of financial limitations.17 A well-known figure in Buffalo Canal District, Mary Remington, was renowned for her strong dedication to social welfare and for supporting women who could not support themselves, operating out of Remington Hall.18 Remington Hall was a place of support for many women as it had support meetings for mothers and nurses, Sunday school, house-keeping lessons, education, recreational programs, etc. Mary Remington demonstrated a better, moral lifestyle to over 100 women who previously ran brothels and was respected for her commitment to helping families overcome adversity.19

The prostitution in the community led to public health issues as well as ethical concerns; many Buffalo reformist initiatives were part of a more significant movement in which groups utilized moral and political campaigning for the suppression of vice.20 In addition to weakening society's moral foundation, reforms contended that prostitution posed serious health hazards to the public, especially concerning the spread of venereal disease. Reformers attempted to diminish the actions of sex workers; it made this stigma worse as they advocated for harsh punishment rather than structural assistance.21

For many women during this time, their experience of engaging in prostitution was further compounded by their ethnicity and financial difficulties; many of the sex workers were German or Irish women. These women experienced discrimination due to the cycle of marginalization that was sustained by public contempt for women employed in the vice industries.22 Organizations like the Christian Homestead Association worked within the district to attempt to diminish the vice but in many cases, blamed women who were prostitutes for their moral shortcomings rather than looking deeper into the structural injustice that led many of the women to prostitution.23

Public Health and Disease

In the 19th century, public health issues, particularly venereal disease, played a significant role in shaping societal and governmental responses to prostitution on Canal Street. Figure 3, "The Genius of Advertising," shows how prostitution was promoted in the 19th century, where men could see the appearance of the women working inside the brothel.24 The image portrayal of women is consistent with the ways brothels are marketed to men, emphasizing the physical attributes of sex workers as part of the attraction.25 This demonstrates how, despite growing public health concerns, prostitutes were still accepted by society or tolerated by individuals because of their profitable endeavours. Many people openly encouraged the prostitution but the public held the women responsible for the rapid spread of venereal diseases among the dockworkers, sailors and the public.26 The increasing prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases led authorities to increasingly associate these medical problems with Buffalo's expanding vice economy.27 Due to the intranet labourers like the sailors and dockworkers who spent time at the brothels and saloons on Canal Street, venereal illnesses spread rapidly. Members of the community were worried by these health concerns; due to this, many individuals advocated for stricter regulation of the prostitution industry as the rates of infections continued to rise.28 This worry around the community led authorities to enact laws to control sex work in the area.29

Figure 3: Comic labelled "The Genius of Advertising."

Despite the goal of preventing the disease and its spread, this strategy led to prejudiced behaviours that marginalized women, and did not consider the role male consumers played in the spread of the diseases.30 Rebecca Yamin detailed that health programs in vice districts were moral crusades: any reformers used the danger of illness to defend more prominent attempts to regulate urban areas and impose middle-class norms.31 Moral and legal measures aimed to combat the prostitution on Canal Street primarily due to public health concerns. Instead of addressing the social and economic issues that supported prostitution or vice in general, these initiatives intended to stigmatize women.32 There was an emphasis on trying to manage and control women and their bodies rather than tackling structural problems. This would draw attention to the systemic issues that focused on the importance and complexity of American public health concerns through the 19th century.

Legal and Moral Reform Movement

Within the 19th century, moral and legal change campaigns against prostitution on Canal Street, reflected more significant conflicts between the need for change and the economy's reliance on the vice sectors. As the public outcry over the perceived immorality of Canal Street rose, authorities and advocacy groups attempted to address these problems through moral campaigns and regulations.33 In Buffalo, the legal struggles were documented in court documents such as those published in the Country Court Journal, where judges often tried women accused of sex work and imposed fines, jail sentences or forced examinations upon them.34

Though it's difficult to ignore how the vice industry provided jobs and income for working-class communities in Buffalo, authorities felt pressured to act due to growing moral objections and concerns for public safety. This approach was flawed and demonstrates how this failed to address deeper issues like poverty and gender inequality within the community. It is unfair to punish women for performing sex work when, in many cases, they had no other economic opportunities and were forced into it by society's limitations.35 Lizzie Lake was a 38-year-old woman who was involved in Buffalo's vice industry; she was involved in a violent altercation at Paddy Moran's saloon while working as a prostitute in the Canal Street neighbourhood.36 Her partner, a boilerman, intervened when a customer attempted to abuse Lizzie and, ultimately he killed the man with his bare hands.37 This demonstrates how dangerous the situation was for women and how murder and vice was normalized within the port. The sailors and dockworkers supplied a constant flow of clients, but they produced a dangerous atmosphere. Many reformers would use stories like Lizzie Lake to call support to combat vice, instead of addressing why women turned to prostitution as they would be criticized and blamed for it.38

These instances demonstrated the judicial system's concentration on penalizing women while mostly neglecting the males who were involved and sustained the industry. Frances Willard, who was the Women's Christian Temperance Union President, stated how she "abhors regulated vice" and felt that any prostitution regulated by laws is unjust.39 Despite their good intentions, these campaigns frequently ignored the structural injustices that led women into sex work, portraying prostitution as a moral failing that could be fixed by personal change.40 Prostitution flourished due to the constant customer base that dock and ship employment offered, many Buffalo working- class residents, especially those living close to the port, were crucial in maintaining the vice industry.41 However, authorities were compelled to act against these practices due to moral and ethical objections and public safety concerns. The intricacy of reform initiatives, which were frequently influenced by conflicting interests and goals, is highlighted by this duality.42 Rebecca Yamin details how reformers-imposed control over public areas and upheld social standards using moral discourse.43 In the end, overlapping social, economic, and political considerations influenced the moral and legal reform movements that targeted prostitution on Canal Street.

Conclusion

The intricate interactions of moral, social and economic factors that influenced Buffalo's Canal Street's transformation into a vice center is revealed by the city's history during the 19th century. Prostitution developed due to the city's economic dependence on the Port of Buffalo's migrant labour force, which introduced vice industries into the city's working-class areas.44 The social injustice of the era, which left many women with few means of subsistence, further exacerbated this economic base.

Broader societal issues were brought to light by attempts to combat the vice economy through legislative and public health reforms. Public health initiatives aimed at preventing venereal diseases often disproportionately targeted women while neglecting structural problems thereby exacerbating prejudice and stigma.45 The Canal Street narrative highlights the difficulties of balancing social reality, moral principles, and economic necessities in urban development. Vice neighbourhoods like Canal Street reflected the conflicts and tensions that come with industrial cultures and functioned as miniatures of significant urban changes.46 Besides shedding light on the past, port history offers insight into the current social reforms and urban growth challenges.47 Port history demonstrates how the movement of people and goods influenced the social structure and economic environment of coastal towns, bridging the gap between urban and maritime history. The Canal Street narrative highlights the difficulties of balancing social reality, moral principles, and economic necessities in urban development.

-

Rachel V. Nicolosi, "Love for Sale: Prostitution and the Building of Buffalo, New York, 1820-1910,"The Exposition 2, no.1 (2014) ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 1-3. ↩

-

Samuel Wilkson, and Marvin Rapp, The Erie Canal's Western Terminus: Commercial Slip, Harbor Development, and Canal District. Buffalo Architecture and History Guidebook, Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, n.d. ↩

-

Rebecca Yamin, "Wealthy, Free, and Female: Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century New York," Historical Archaeology 39, no. 1 (2016), 4--18. ↩

-

Yamin, "Wealthy, Free and Female," 10-18. ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale", 1-4. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Map of Retail Places of Business in the District Covered by the Christian Homestead Ass'n of Buffalo], map, New York Heritage Digital Collection (2012). https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/VHB001/id/9132/rec/43 ↩

-

Figure 1: [Map of Retail Places], map. ↩

-

Unknown Author, "Map of Retail Places of Business." ↩

-

Marilynn Wood Hill, Their Sisters' Keepers: Prostitution in New York City, 1830-1870, University of California Press, Berkeley (1993). ↩

-

Joyce Fraser, Prostitution and the Nineteenth Century: In Search of the 'Great Social Evil, Reinvention: A Journal of Undergraduate Research 1, no. 1 (University of Warwick, 2008). ↩

-

Jeff Z. Klein, "Buffalo's Vanished Maritime Past" Belt Magazine, Jul. 9, 2020 ↩

-

Figure 2: [The Canal Harbor, Buffalo, N.Y], photograph, Detroit Publishing Co. (n.d). ↩

-

Mark, Goldman, High Hopes: The Rise and Decline of Buffalo, New York, State University of New York Press (1983). ↩

-

Hill, "Their Sisters' Keepers." ↩

-

Yamin, "Wealthy, Free and Female," 4-8. ↩

-

Hill, "Their Sisters' Keepers." ↩

-

Angela Keppel, Buffalo's Canal District, Part 2: Dante Place --Buffalo's Little Italy Discovering Buffalo, One Street at a Time, April 4, 2014. ↩

-

Keppel, "Buffalo's Canal District." ↩

-

Fraser, "Prostitution and the Nineteenth Century." ↩

-

Scott W. Stern, "The Venereal Doctrine: Compulsory Examinations, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and the Rape/Prostitution Divide," Berkely Journal of Gender, Law & Justice 34, no. 1 (2019). ↩

-

Unknown Author, "Map of Retail Places of Business." ↩

-

Steve Cichon, The Buffalo You Should Know: Before There Was Canalside, Buffalo Stories Archives & Blog, Mar. 12, 2016. ↩

-

Figure 3. [Comic labelled "The Genius of Advertising"], illustration, Prostitution (1880). ↩

-

Donati, "Prostitution." ↩

-

Donati, "Prostitution." ↩

-

Stern, "The Venereal Doctrine," 160-170. ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 6-7. ↩

-

Stern, "The Venereal Doctrine," 168-170. ↩

-

Unknown Author., "Map of Retail Places of Business." ↩

-

Hill, "Their Sisters' Keepers." ↩

-

Yamin, "Wealthy, Free and Female," 12-18. ↩

-

Yamin, "Wealthy, Free and Female," 10-18. ↩

-

Albert Haight, Country Court Journal January 31, 1875, through April 27, 1876, Erie County (New York) Court Judge Haight, Vol. IV Transcript, Courtesy of the Western New York Genealogical Society, New York Heritage Digital Collections, Jan. 31, 1876. ↩

-

Stern, "The Venereal Doctrine," 162-170. ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 7. ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 7-8. ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 7-8. ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 10-11. ↩

-

Hill, "Their Sisters' Keepers." ↩

-

Nicolosi, "Love for Sale," 1-4. ↩

-

Alex Smolak, "White Slavery, Whorehouse Riots, Venereal Disease, and Saving Women: Historical Context of Prostitution Interventions and Harm Reduction in New York City during the Progressive Era," Social Work in Public Health 28, no. 5 (2013), 496--508. ↩

-

Yamin, "Wealthy, Free and Female," 4-8. ↩

-

Yamin, "Wealthy, Free and Female," 10-18. ↩

-

John C Burnham, "Medical Inspection of Prostitutes in America in the Nineteenth Century: The St. Louis Experiment and Its Sequel," Volume 9 Prostitution (Berlin, Boston: K. G. Saur, 1993). ↩

-

Smolak, "White Slavery, Whorehouse Riots," 496-508. ↩

-

Wilkson and Marvin, "The Erie Canal's Western Terminus." ↩