Indigenous Settlement

The Early Indigenous Settlements of Cootes Paradise and the Ecological Importance of the Wetlands Surrounding Burlington Bay

Jody Brown Nolan

Hamilton - 2022

When we look at and explore large bodies of water, such as the Great Lakes, it is hard to see past its grandeur, and often, historians, researchers, and the general population tend to focus on the bigger picture. As a result, small factors become overlooked even though they may have significant impacts and consequences. Cootes Paradise was an integral ecosystem shaped by human intervention over thousands of years, allowing early Indigenous cultures in and around Burlington Bay to thrive and evolve to permanent settlers before European occupation. This essay will examine how Cootes Paradise and its lands were productive, maintained, and enhanced by early Indigenous cultures through exploring the importance of the Princess Point culture and how the introduction of agriculture changed the wetlands and consequently changed the way Indigenous peoples settled within the area. Finally, to understand how its original settlers enhanced the wetlands, one must also consider how quickly the arrival of Euro-Canadians impacted them. Environmental influences on Cootes Paradise by Euro-Canadians came through landscape changes and their cultural views of wetlands being seen as dangerous obstacles which hindered development, restricted travel, and impeded commerce.

Wetlands, swamps, ponds, and marshes are not grand; they are often seen as being “grotesque” and “monstrous” in some present-day cultures.1 Many people, past and present, have presented a narrative of these areas being “backward and stagnant.”2 However, not all cultures have seen these marshy areas in this way. As the environment continues to change, there is a greater understanding of the ecological significance of wetlands and how they aid large water systems by filtering out the impurities caused by society. As highlighted by Nelson, the Great Lakes is not one bioregion, but many environments interconnected through a natural balance between water and land and humans and nature. To master this balance, Indigenous populations of all eras were constantly evolving and learning how to strategically control flora and fauna in and around the wetlands.3 Indigenous cultures have long known the importance of wetlands to their survival, evident by the earliest people to pass through the area of Cootes Paradise during the Early Archaic period (10,000–8,000 B.P.) to the Woodland, Princes Point, and Iroquoian cultures.4 Human alteration of the watershed around the Great Lakes did not only happen in the modern era; it began thousands of years ago and long before the arrival of any European.5

Figure 1: Bone harpoon recovered from the East Midden on the Princess Point promontory

Figure 2: Princess Point vessel, found near the lower levels of the midden on the promontory

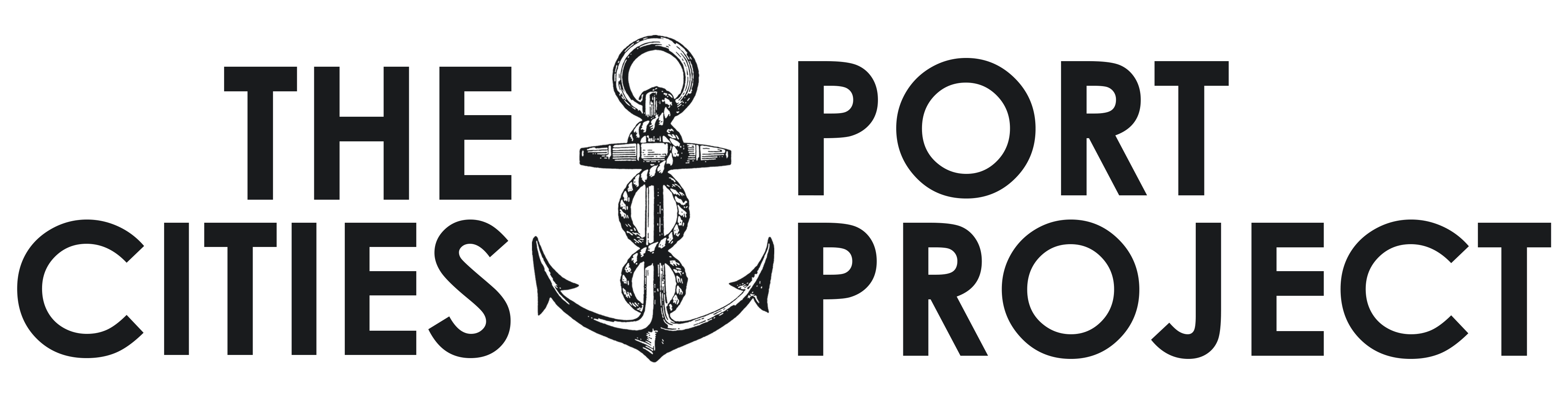

There is a promontory located within Cootes Paradise called Princess Point. Archaeological research at Princess Point has uncovered abundant artifacts showing an extensive history of human development, growth, and transformation.6 Over 169,000 artifacts have been recovered from this area with a majority of these artifacts being faunal and other food remains. However, finds such as pottery from multiple different eras (Figure 1), lithic fragments, net sinkers, beads, maize kernel fragments, and a bone harpoon (Figure 2) have also been recovered.7 This promontory confirms human activity through multiple stages of pre- and post-European contact. Cultural evidence found at this site ranges from an intact notched point identified as belonging to the Early Archaic period of the Paleo-Indians (10,000–8000 B.P.) to proof of activity during the Middle Woodland (400 B.C.–A.D. 500), the Early Late Woodland (A.D. 500–1000), and the entire span of the Ontario Iroquoian tradition (A.D. 1000–1650). Cultural excavations end with the post-contact period (A.D. 1650 to the present day), where a clay pipe and modern-day refuse have been found.8

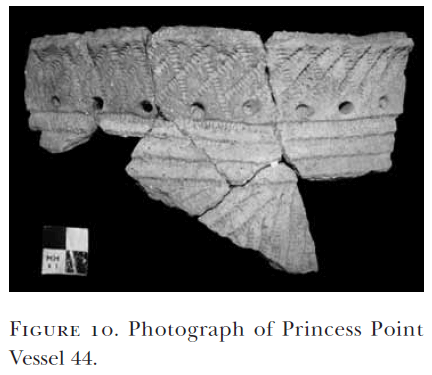

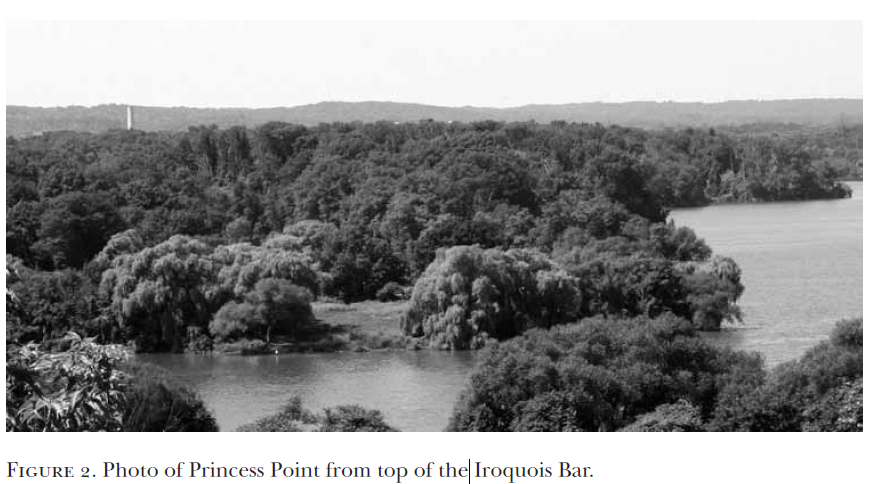

The promontory was named after the Princess Point Complex, which occupied the space during the Early Late Woodland period.9 Along with the abundance of artifacts found on the promontory of Princess Point, there are also small sites along the water’s edge at the bottom of the ravine (Figure 3).10 These sites have been described as being “unique to Cootes Paradise.” 11 Typically, access to locations

Figure 3: View of Princess Point as seen from the Iroquois Bar

along the water’s edge is from higher grounds, but access to these sites is through the lower basin. Smith notes that these camps were short-term seasonal locations, and their exact purpose is currently unknown. However, he postulates that these sites were chosen because of how they were accessed, but more research will have to be completed to conclude why the lower level posed a more favourable access point.12 Other than European settlers, the people of the Princess Point Complex had some of the most influential practices that modified and impacted the marshy area and landscape of Cootes Paradise.

Wild rice was a continuous staple for many Indigenous cultures prior to and during the introduction of corn. Cootes Paradise has not always been full of the cattails that engulf the area today. The abundance of wild rice could date back as early as the last ice age. Since this area was not permanently settled during the Early Archaic period of the Paleo-Indians, it would have been seasonally visited to harvest in the western marsh of Cootes Paradise and Burlington Bay.13 Wild rice dominated the marsh between 1 CE to 1200 CE,14 and as cultural transportation, innovation, and knowledge evolved, so did the ability to collect and manage this valuable resource. Through a series of core samples taken from the shorelines in Cootes Paradise, there is an indication that wild rice was predominated in the marsh until approximately A.D. 1100, which coincides with the occupation of the Princess Point culture.15 After this time, wild rice production began to fall and was replaced by cattails and other domesticated and non-domesticated plants within the marsh. Occupation patterns had not changed, so what was the reason behind this significant environmental shift? Due to the increased knowledge of maize agriculture in Indigenous cultures and its benefits over wild rice, could this change in the marshland’s flora be due to increased production of maize within this area? Human activities affected the environment, and this shift in the cultivation of a food source gives evidentiary support on how early Indigenous cultures impacted the wetlands and surrounding areas.

Early Indigenous peoples at Princess Point have been referred to as “Canada’s first crop cultivators,” and by “A.D. 500 they were growing maize as a supplement to their existing regime of foraged resources.”16 Maize was experimented with and altered in different ways and modified into the corn that is grown in Canada today. In the beginning, most maize was not grown in farmer’s fields but rather near the marsh’s shorelines.17 Saunders argues that plants were not selected at random, as florae were experimented with and chosen when they fit “within the cultural context of each society” either as food, medicine, or for spiritual value.18 The wetland area where the Princess Point culture preferred to live was the perfect environment to introduce maize agriculture since moisture retaining, well-drained, and sandy loams were ideal soil conditions needed for cultivating maize.19 However, the move from harvesting wild rice to growing maize as the main carbohydrate in the Middle Woodland diet was not instant. Its evolutionary process began with floodplain agriculture20 followed by learning how to transplant, store, disperse, and manipulate the seeds.21 Domesticating plants and engineering them to fit the desired environment is indisputable proof of control over the ecosystem.22

There were many advantages to the switch from a wild rice to a maize-based carbohydrate diet. Wild rice was more nutritious, but sensitivity to water levels and difficulties in harvesting this stock made the ease of growing maize more appealing. Maize was easily harvested because it grew next to settlements and did not require watercraft to gather it. The crop was also more reliable when storing it for extended periods of time23 and it could be kept for up to 2 years which allowed it to be consumable over the winter months and available for a longer period of time in general which was especially beneficial if the following year produced a poor harvest.24 Wetlands that attracted a wide range of animals, year-round fishing, and a carbohydrate source that could be stored for an extended time were all essential components in converting a nomadic or semi-nomadic culture into one that would establish a permanent, year-round settlement.

Warrick argues that because Princess Point and later Iroquois sites overlap, there is a strong possibility that the Early Iroquoian are descendants of the Princess Point culture.25 There is also strong evidence supporting the pattern usage of wetlands within these two cultures since this usage is identical to each other.26 The original settlers of these areas not only cultivated wild plants but used their knowledge to their own benefit to control a wide array of animal species as well.27 From generation to generation and tribe to tribe, sharing essential environmental knowledge to manipulate wetlands was imperative to the survival of early Indigenous cultures.

The Neutrals were an Iroquoian group who, before the arrival of French explorers, approximately 1600 – 1650 A.D., occupied the space at Cootes Paradise year-round. The Neutrals were some of the first permanent settlement sites around Cootes Paradise. This settlement location is consistent with their culture as Neutral sites were frequently found near wetlands.28 Availability of multiple resources would have been necessary when choosing this site for permanent settlement. The Neutrals needed large amounts of wood to build their villages successfully and because white cedar grows abundantly within low-lying wetland areas, this would have been a significant component when choosing Cootes Paradise. Besides housing materials, wetlands never faltered in providing the perfect environmental habitat for wildlife. Advances continued in maize agriculture and cornfields also aided in attracting deer, which offered another resource that aided in the permanent settlement of the Neutrals.29

Today we are more knowledgeable about the importance of wetlands and how the water-plant-human interrelationship strongly depends on one another.30 Indigenous cultures viewed wetlands as life, as wetlands provided food, shelter, medicine, transport, tools, and even weapons. Wetlands also held spiritual and cultural significance evident through ceremonial, social, political, and economic activities, and served as natural boundary markers for tribes. However, not every culture saw the beauty and significance of wetlands and dominant societies viewed them as a symbol of backwards and stagnant civilizations, particularly unproductive lands producing people and cultures just as wild and savage as their murky waters.31

Altering wetlands was not a new practice to early Euro-Canadians.32 O’Sullivan argues that altering wetlands was a cultural norm practiced in central and northwest Europe since the Middle Ages when wetlands were believed to be dangerous; these views spilled over to the New World.33 The task of Europeanizing these surroundings by taming nature’s wildness fell upon the local government and its newest residents.34 Waterways were a means for commerce and used to ship products efficiently for the most profits. The Euro-Canadians had to civilize the lands and create a working space where commerce and trade could occur.35 The sandbar (the Iroquois Bar) that separated the marshy area of Cootes Paradise was an obstacle standing in the way of progress. By physically changing the landscapes, the space became easier to manage and exploit as needed. Government authorization in 1823 for construction of the Desjardins Canal would see a channel cut through the Iroquois Bar. The construction started in 1826, and by 1837 the canal was open.36 The Desjardin Canal was promoted by Peter Desjardin, who resided in the village of Cootes Paradise and was aware of the trans-shipment difficulties through the shallow marsh.

Along with cutting through the Iroquois Bar, a channel was also dredged through the marshland. Two years after the canals opening, complaints were made by commercial shippers who attempted to use the canal. The channel was challenging to navigate, and by 1854, a railway bridge was built across it, rendering the canal useless for commercial shipping. Euro-Canadian settlers did not foresee issues when opening Cootes Paradise to the waters of Lake Ontario, but rather this change was seen as typical construction that was no different on the Bay than anywhere else in the colonizing world.37 The wetlands were often regarded as wastelands, and by taming the wildness, Euro-Canadians were maximizing the productiveness of an otherwise wasted area.38

Early Europeans’ unromanticized views of wetlands and their lack of environmental knowledge led to changes in the landscapes to suit their commerce and cultural needs. The Iroquois Bar was an obstacle that needed to be removed. The sandbar prevented the lake waters from entering and cleaning the swamp’s waters and to the early Europeans, it was because of the Iroquois Bar that the marshy wasteland existed.39 Seventy-eight years after Desjardins first petitioned for the canal to be built, opinions about the importance of the Iroquois Bar and Cootes Paradise wetlands did not change. Holden wrote in 1898 that Cootes Paradise and Burlington Bay were “evidently intended by nature to be part of the Lake,” that the Bar, made up of accumulated debris from a storm, inadvertently separated its waters from ultimately joining those of Lake Ontario.40 European settlers felt they were changing the landscape and altering it back to its original state and they did not understand the significance of keeping Cootes Paradise and Burlington Bay separated. However, Iroquois Bar was not a result of accumulated debris from a storm but an early post-glacial lake embankment.41 The decisions that were made to alter the landscape of Cootes Paradise still impact our current environment today.

Until European settlers arrived, Cootes Paradise was a true marshland of shallow water and cattails filled with flora and fauna, an environment that took thousands of years to establish.42 Nelson notes that the Desjardins Canal resulted in “cross-cultural exchange and environmental manipulation.”43 Ultimately, the wetlands were introduced to the fluctuating waters from Lake Ontario and were carelessly opened to invasive fish and plant species.44 The introduction of carp resulted in the utmost change regarding the ecological balance of the wetlands. Today an estimated loss of 85 percent of the plant coverage is caused by the carp which enters Cootes Paradise through the Desjardin Canal channel.45 Still, environmentally, the region of Cootes Paradise is one of Canada’s most biologically diverse areas.46 Today the City of Hamilton boasts it as being “one of the highest biodiversity of plants per hectare in Canada and the highest biodiversity of plants in the region.”47 Overall, there are a recorded 1,582 species of flora and fauna in the area with more than 50 species at risk and 35 endangered.48 The biodiversity found at Cootes Paradise did not happen by chance; through respect of the land and the environment for thousands of years and Indigenous ingenuity, flora and fauna flourished in this area. However, it only took two hundred years of European settlement and growth to reshape nature, making this area vastly different from the land and waters of original Indigenous settlers.49

Marshes, bogs, swamps, and wetlands were not the wastelands Euro-Canadians portrayed them to be. They were certainly not “unproductive or ruined or unsettled lands.”50 Cootes Paradise, surrounding areas, and beyond have been of the utmost importance to the survival and growth of Indigenous cultures. These waters and lands have been modified and productively used for thousands of years. We may never fully understand how the Paleo-Indians, Late Woodland, Princess Point, and Iroquois cultures impacted the wetlands but what we do know is that early Indigenous cultures did not choose this area at random. It was carefully selected and exploited accordingly, ideally suited for the growth of food and the development of human habitation. Over time, increased horticulture through utilization and knowledge of the wetlands and their vast resources turned this once nomadic culture to the first permanent settlers of Cootes Paradise and the surrounding area of Burlington Bay.

-

Rod Giblett, Canadian Wetlands: Places and People vol. 7 (Bristol: Intellect Books Ltd, vol.7 2014), 15. ↩

-

Giblett, Canadian Wetlands, 15. ↩

-

John William Nelson, “The Ecology of Travel on the Great Lakes Frontier: Native Knowledge, European Dependence, and the Environmental Specifics of Contact,” The Michigan Historical Review 45, no.1 (2019): 6-8. ↩

-

Helen R. Haines, David G. Smith, David Galbraith, and Tys Theysmeyer, “The Point of Popularity: A Summary of 10,000 Years of Human Activity at the Princess Point Promontory, Cootes Paradise Marsh, Hamilton, Ontario,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 35, no.2 (2011): 233 ↩

-

Nelson, “Ecology of Travel,” 4. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 232. ↩

-

Figures 1 and 2: Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 244-245. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 233, 245. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 232. ↩

-

Figure 3: Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 236. ↩

-

David G. Smith, “Recent Investigation of Late Woodland Occupations at Cootes Paradise, Ontario,” Ontario Archaeology, no. 63 (1997): 4. ↩

-

Smith, "Late Woodland Occupations," 13 ↩

-

Nancy Barbara Bouchier, Ken Cruikshank, and Graeme Wynn, The People and the Bay : a Social and Environmental History of Hamilton Harbour (Vancouver, British Columbia: UBC Press, 2015), 7. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 235. ↩

-

Smith, "Late Woodland Occupations," 12. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 232. ↩

-

Bouchier, Cruikshank, and Wynn, The People and the Bay, 7. ↩

-

Della N. Saunders, “Princess Point Palaeoethnobotany,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto (2002), 3. ↩

-

Krahn, Thomas Herman, “A Location Analysis of Early Seventeenth-Century Neutral Settlements, Southern Ontario,” Master of Arts thesis, Trent University (2007), 13. ↩

-

Gary Warrick, “The Precontact Iroquoian Occupation of Southern Ontario,” Journal of World Prehistory 14, no.4 (2000): 432. ↩

-

Saunders, “Princess Point Palaeoethnobotany,” 164. ↩

-

Saunders, “Princess Point Palaeoethnobotany,” 176. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 249. ↩

-

Warrick, “Precontact Iroquoian Occupation,” 432. ↩

-

Warrick, “Precontact Iroquoian Occupation,” 434. ↩

-

Warrick, “Precontact Iroquoian Occupation,” 434. ↩

-

Nelson, “Ecology of Travel,” 3. ↩

-

Kran, “Neutral Settlements," 18. ↩

-

Kran, "Neutral Settlements," 19. ↩

-

Saunders, “Princess Point Palaeoethnobotany,” 3. ↩

-

Giblett, Canadian Wetlands, 15. ↩

-

Aidan O’Sullivan, “Europe’s Wetlands from the Migration Period to the Middle Ages: Settlement, Exploitation, and Transformation,” in The Oxford Handbook of Wetland Archaeology (Oxford University Press, 2012), 2. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, “Europe’s Wetlands,” 1-2. ↩

-

Bouchier et al., The People and the Bay, 8. ↩

-

Bouchier et al., The People and the Bay, 8. ↩

-

“The Desjardins Canal,” Ontario Heritage Trust, accessed March 2022, https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/plaques/desjardins-canal. ↩

-

Giblet, Canadian Wetlands, 79. ↩

-

Giblet, Canadian Wetlands, 124. ↩

-

Mary Rose Holden, Burlington Bay, Beach, and Heights, in History (Hamilton, ON: William T. Lancefield, 1898), 10. ↩

-

Holden, Burlington Bay, 10. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 234. ↩

-

Smith, "Late Woodland Occupations," 5. ↩

-

Nelson, “Ecology of Travel,” 4. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 235. ↩

-

“Cootes Paradise Marsh,” City of Hamilton, accessed March 2022, https://www.hamilton.ca/city-initiatives/our-harbour/cootes-paradise-marsh. ↩

-

Haines et al., “Point of Popularity,” 235. ↩

-

“Cootes Paradise Marsh.” ↩

-

“Cultural Heritage,” Cootes to Escarpment EcoPark System, https://www.cootestoescarpmentpark.ca/cultural-heritage ; “Cootes Paradise Marsh.” ↩

-

Bouchier et al., The People and the Bay, xv. ↩

-

Giblet, Canadian Wetlands, 79. ↩