All Hands-on Deck

The Transformation of Hamilton Harbour and its Workers During World War II

Hayden Miller

Hamilton - 2022

By all accounts, the Canadian war effort during World War II was a remarkable achievement both abroad and at home. The Port of Hamilton was no exception, and it became instrumental in meeting the needs of the Canadian and British navies in refitting ship hulls, fabricating steel for ship construction and manufacturing essential machinery such as boilers, guns, and electrical systems. The Port of Hamilton was essential to producing naval equipment needed to outfit the navy, replace destroyed allied ships, and ensure that the Atlantic supply route between North America and Britain was not disrupted. The eruption of World War II shaped Hamilton’s maritime landscape into a major industrial centre and shipbuilding hub and, at the same time, transformed its workers into a diverse labour force such as relying on female labour during the war years. Despite the influx of unskilled and new workers in the shipbuilding industry causing tensions with more experienced workers, workers were still able to use the demand for labour and the large number of workers to their advantage through trade unions and maintaining a strong political voice.

During World War II, the Port of Hamilton experienced significant change to its maritime landscape. Its geography was altered and so was its function as an industrial manufacturing hub in the Great Lakes region. Before World War II, the shipbuilding industry in Canada was in a dismal state. Pritchard explains that Canada's shipyard industry was small, often idle and incapable of building large, military-grade vessels.1 At the time, there were only three working shipyards in Canada employing 4,000 men2 including Canada Steamship Lines based in Montreal, Collingwood Shipbuilding Company in the Great Lakes region, and Burrard Dry Dock Limited out of Vancouver.

Hamilton reflected this reality as a small city with a population of 155,000, with a limited shipbuilding industry that had never built a complete warship before. Despite the city's small size, inexperience in shipbuilding, and lack of proximity to the St. Lawrence Seaway, it was well-positioned to meet the industrial needs of the Canadian navy and its allies. A pool of skilled and semi-skilled labourers resided in the city and available factories, such as The Dominion Foundries and Steel Company and The Steel Company of Canada, could be retooled to meet shipbuilding needs and were close to transportation routes by water, rail, or road. The Great Lakes region, and in particular Hamilton, became front and center in the industrialization effort to support the needs of Canada’s war effort.

Hamilton's proximity to the St. Lawrence Seaway and its pool of labourers and manufacturing capabilities, aligned well with the Canadian government’s perspective to increase production. Canada's Minister of Munitions and Supply, C.D. Howe, was tasked with developing Canada’s industrial base. Howe led war procurement and worked alongside industrialists to fund plant expansion and retool facilities. Forbes argues that Howe favoured central Canada over the Maritimes because he wanted to establish a strong industrial base that would lead Canada into the postwar era. As noted by Forbes, C.D. Howe and his controller’s “vision of a centralized manufacturing complex closely integrated with the United States apparently did not include the Maritimes in any significant role."3 This national objective favoured Hamilton because of its location in central Canada, proximity to the American border, and access to transportation routes, which were all viewed as essential factors to transition to peacetime production.4

One of Hamilton’s major players in wartime shipbuilding was the Steel Company of Canada (Stelco), founded in 1910, which played a significant role in shaping Hamilton Harbour and its workforce. Stelco was a microcosm of Hamilton Harbour’s industrialization and transformed workforce. In October 1939, The Hamilton Spectator reported the ramping up of industry in response to the war effort and the subsequent benefits for the city: "War orders are gearing Hamilton factories to activity reminiscent of the boom days. Already substantial purchases of war materials have been contracted for, and further business is expected…"5 Hamilton's manufacturers, such as Stelco, benefitted from government support and private enterprise as they sought to increase production quickly to meet the demand. By 1941, Stelco along with Algoma Steel received approximately four million dollars in federal funds6 to support the fabrication of steel and the equipment and artillery needed to support Canada’s war effort.

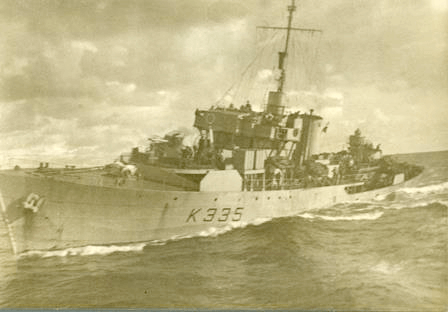

In response to Canada’s naval needs, the expansion of the shipbuilding industry was swift and financially supported by the government and industrialists. In 1939, The Hamilton Spectator reported unfinished ships would be transported from Toronto to Hamilton, and an outfitting yard would be established in Hamilton Harbour. An official from the Munitions Department explained that “the warehouse [would] provide ample space for a fitting-out slip, while tramway facilities [were] available for workers, and railway tracks for equipment [would run] to the docks.”7 This financial support continued in 1942 as reported by The Hamilton Spectator citing Controller A.H. Frame who explained that establishing a shipbuilding facility in Hamilton would make for efficient production because of its land-locked harbour, heavy industrial base, and proximity to natural resources. Likewise, in June 1943, The Hamilton Spectator reported that Hamilton Harbour would be charged with equipping hulls of Corvette and Algerine warships (see Figure 1) that floated in from other shipbuilding centres, noting that “several hundred men [would] be employed in the new war project and the large warehouses of the commission [would] be used as a fitting-out shop.”8 Once completed, the warships were transported down the St. Lawrence Seaway for escort duty in the Atlantic Ocean. By the end of the war, there had been 210 warships built in the Great Lakes region between 1940 to 1945 including 50 Corvettes, 96 minesweepers, 62 Algerines, and 59 Fairmiles.9

Figure 1: A Canadian Corvette: HMCS Frontenac at Sea

Hamilton Harbour's coastline was transformed to accommodate the newly established shipbuilding industry. According to the Hamilton Harbour Commission, the harbour experienced a building boom well into the 1940s. With the help of federal government grants, a new terminal dock was built, adding industrial sites and storage facilities, new rail sidings and roadways, and a new naval training base called the HMCS Star.10 Likewise, industrial warehouses were refitted to meet the needs of the shipbuilding industry, such as the Commissioners’ Wellington Street Warehouses that were taken over by the Naval Shipbuilding Branch to outfit submarine-chasers such as Fairmiles and minesweepers called Algerines.11 New facilities and production capacity allowed Ontario to receive a total of 15.1 percent of federal shipbuilding contracts12 which employed 580 workers in 1939 in the Great Lakes region compared to 10,158 by 1944. By 1944, the Great Lakes workforce in the shipbuilding industry accounted for 14.1 percent of the national workforce.13

Equally significant as these improvements was the contribution made to the war effort by Hamilton’s workers. Hamilton had a concentration of skilled and semi-skilled workers in steel and manufacturing sectors and factories who were capable of meeting the demands of wartime production; however, the most significant challenge was establishing a stable, adequate labour force to keep up with industrial expansion and supply needs. For most wartime workers, gains were made working in the war industry, and the shipbuilding industry was no exception. War industry work was welcomed following years of economic uncertainty during the Great Depression. Families enjoyed long-awaited financial security with sons in the army and others working in factories. Wartime work was attractive because overtime was available, and many people worked up to sixty hours a week.14 The average annual salary of a worker increased from $956 in 1938 to $1525 by 1943.15

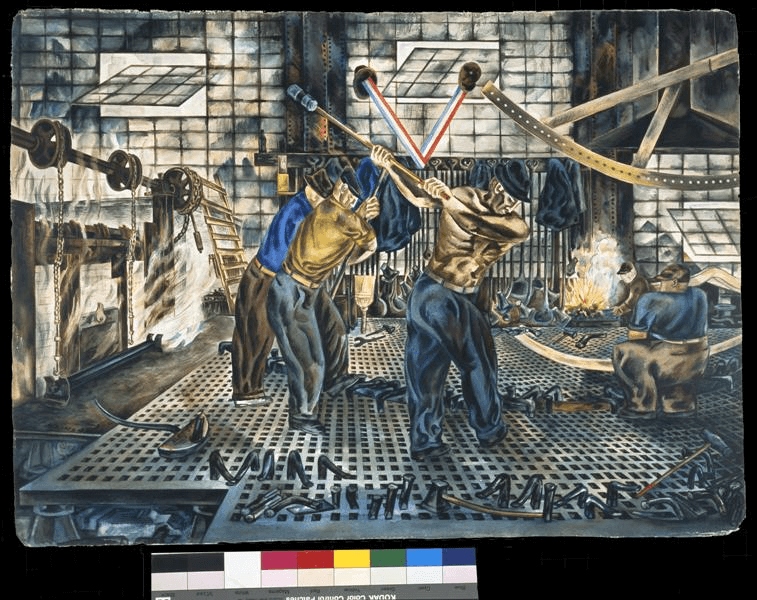

Canadians answered the call for wartime labour; however, it was challenging to establish a stable, cohesive workforce. Workers often moved to the city from the countryside looking for work but lacked experience in the shipbuilding industry and were thus unskilled for this specific type of work.16 Cavan Akins, for example, highlights the physical demands of being in the shipbuilding industry through his 1942 painting (see Figure 2).17 The new unskilled workers were seen as outsiders and looked down upon by more experienced shipbuilders.

Figure 2: A Shipshape Workforce

Tension between seasoned, urban workers and new, rural workers developed resulting in divisions in the workforce based on experience and geographic origin. To combat this divisiveness, Pritchard points to efforts made by the Toronto Shipbuilding Company to develop camaraderie between workers and minimalize loneliness with the launching of an in-house publication called The Compass. Published monthly, The Compass contained news, jokes, cartoons, and other helpful information. In-house publications, ship launchings, and war campaigns18 were all attempts to reduce the persistent division in the shipbuilding labour force such as promoting communication and friendships between the workers and increasing trust and communication between workers and management.

Many shipbuilders were lured out of retirement to assist the war effort alongside a sizeable workforce with industrial experience in the Great Lakes region; however, as Pritchard notes, training this amount of workers in the ship yards “became a never-ending task".19 The Department of Labour used several approaches to quickly train a large influx of inexperienced workers, such as tasking individual shipyards with building one type of ship to reduce the amount of training per ship yard.20 They also differentiated training by having some workers learning in school while others trained in the yards.21 In some instances, training requirements and programs implemented by the government were the root of tensions between skilled tradespeople and unskilled or semi-skilled workers. New hires were required to complete training programs to ensure their “future occupational adaptability”22 in preparation for the post war years. As Madsen explains, "whether male or female, training and on the job, practise leading to experience were imperative for the unskilled and semi-skilled workers brought into wartime factories and places of production."23 This training for new hires did not sit well with tradespeople who felt their four-year apprenticeship programs were not valued.24 The rapid increase of the workforce was not an easy transition, as the workforce multiplied from a relatively small, exclusive group of skilled tradesmen to a largely unskilled group needing training. Both groups took to the sidelines and cited differences in training and treatment as the result in the development of rifts between the worker groups.

The relentless demand for labour diversified the workforce, as women became involved with wartime production to fill the labour gap. In 1943, Ontario’s shipyard industry reached its highest number of female employees which was only 578 women or 6 percent of the workforce.25 Nevertheless, women bolstered the workforce and persevered through difficult working conditions such as heavy and dirty work that was often completed outdoors in all weather conditions. Tensions between female and male workers developed and were exacerbated by prejudices and unequal compensation for the same work. Pritchard explains, that “women also paid social and psychological costs to work in the shipyards” because prejudices “were more firmly rooted” in shipbuilding than in newer industries.26 Male workers took exception to females who were seen as taking traditional male jobs and viewed as incapable of the demanding work. The workforce again faced further division and ongoing tension brought on by a rapidly growing workforce that was needed to maintain wartime production.

The expansion of the shipbuilding industry shaped a diverse and divided workforce and at the same time, provided an opportunity for workers to organize in the face of government interference, wage freezes, and imposed conciliation between workers and employers. During World War II, the labour force was shaped and controlled by government policy, such as controlling the placement of factory workers and refusing to consider bargaining with organized labour. Wartime administrator H.R Howe proclaimed, “there can be no profits in this war to capitalists, labour or anyone else.”27 The government was unreceptive to organized labour and “rather than acknowledge the rights of trade unions to bargain collectively or to strike, the government continued to impose compulsory conciliation until late in the war.”28 Likewise, wages and prices were set by the Wartime Prices and Trade Board. Subsidies were paid out to companies to compensate for the cost of imports, and living bonuses were given out because of the lack of wage increases.29 The government's attempt to satisfy workers with salary bonuses only went so far in placating workers who were essential to the war effort. Despite worker diversity, a common government opponent served to unite workers in one single minded goal: to improve working conditions.

The volume of workers translated into strength in numbers and the production demands of World War II gave workers leverage in the shipbuilding industry. Workers were essential in maintaining high production levels necessary for the war effort, and this reality made way for trade unionists to carve out a role in wartime factories. Labour groups agreed to keep management aware of local issues that affected workers and subsequent production.30 The government’s refusal to recognize organized labour drove workers to organize locals with unions such as the United Steelworkers of America and use their position as essential workers to pressure for improved working conditions and compensation. Madsen argues, that “wartime was an opportunity for further organizing based on larger memberships as well as securing union recognition and bargaining rights in those plants and industries not already unionized.”31 The government may have controlled workers, but their sheer numbers gave them the impetus to organize and politicize themselves as a significant player in wartime industry.

Some factories, such as Stelco, quickly pushed their mills to near full capacity by changing operational procedures such as implementing "a third shift at their plate mill in October 1941.” This third shift allowed the mill to produce between 16,000 and 17,000 tons monthly which exceeded their average production numbers.32 Likewise, Stelco underwent technological advancements by introducing new machinery to increase its capacity and efficiency and decrease the number of workers needed. Heron notes that “a visitor to the plants would have been struck by the elaborate new machinery, which reduced or eliminated the firms’ reliance on both highly skilled craftsmen and unskilled labourers.”33 Stelco became a primary beneficiary in the industrialization of Hamilton Harbour and used the economic boom as an opportunity to expand and modernize its operations.

Despite trying to keep up with wartime demands, steel companies experienced a shortage of workers as a result of the war. Like many other mass-production industries, workers changed jobs frequently, partly because of economic instability in the manufacturing sector coupled with intolerable working conditions.34 The labour force shrank as more men enlisted in the war effort and years of restricted transatlantic immigration during the Great Depression continued. As a result of the war effort, manufacturing companies such as Stelco became more attractive to workers due to high demand, high wages, and newfound economic stability. The company managed to grow and train its workforce to keep up production levels; however, its labour force quickly diversified. Madsen explains, that "the skilled industrial workforce remained overwhelmingly male” and even though “women worked the same shifts as men, the pay was often less, and the provincial government required employers to have permits for overtime in the case of females." 35 Women were an attractive commodity for the company because they shored up the workforce and were cheaper to employ.

As the government demanded more steel production, steel producers introduced new technology to reduce the demand for both skilled and unskilled workers. New machinery increased production but did not improve the poor working conditions and long twelve-hour shifts that were “harsh [with] autocratic supervision, and high accident rates.”36 However, difficult working conditions led to dissatisfaction in the labour ranks. A larger workforce and the necessity to maintain steel production allowed workers to demand improved working conditions and forced Stelco to make labour concessions. Despite government control over wartime labour and reluctance to introduce legislation to permit collective bargaining, the government “eventually acknowledged industrial unionism and introduced provincially-mandated collective bargaining between employers and organized labour covering the Hamilton area.”37 Madsen notes that “the balance of forces at Stelco gradually shifted to the workers”38 and by December 1944, the Supreme Court of Ontario certified local 1005 of the United Steelworkers of America union.

The Stelco workforce was initially unorganized going into the war and highly regulated by the Canadian government. However, the more indispensable workers became to maintain wartime production, the more organized labour made strides in negotiating changes to working conditions in the steel mill. The Second World War politicized Stelco's labour force into a strong, organized body with a large union membership and political power. In 1944, The Globe and Mail reported a decision by the Ontario Regional War Labour Board ordering Stelco to increase the hourly wage of workers retroactively39 following a union application filed against the company when it refused to negotiate workers’ wages. Madsen argues that “wartime was an opportunity for further organizing based on larger memberships as well as securing union recognition and bargaining rights in those plants and industries not already unionized.”40 Labour in Hamilton transformed into highly organized unions capable of shaping working conditions and changing the nature of steel manufacturers such as Stelco.

In conclusion, Hamilton Harbour’s maritime landscape was shaped by industrialization brought on by the Second World War and the subsequent transformation of its labour force. The Port of Hamilton became a major industrial center that retooled its workforce into a diverse yet well-trained group with political power to negotiate with industry and government. Hamilton’s maritime location, perched on Lake Ontario, connected to the St. Lawrence Seaway, and being near transportation routes, paved the way for establishing a manufacturing industry with a strong labour foundation. Hamilton's shipbuilding industry quickly faded following World War II due to government disinterest in maintaining a strong naval power. Despite the lack of interest, the legacy of the labour movement remained an integral part of the maritime landscape in Hamilton.

-

James S. Pritchard, “Shipbuilding in Prewar Canada,” in A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilding during the Second World War (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011), 6. ↩

-

Pritchard, “Shipbuilding,” 6. ↩

-

Ernest R. Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity: The Maritimes and the Industrialization of Canada during the Second World War,” Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region 15, no. 2 (1986): 5, https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/12094. ↩

-

Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity,” 21. ↩

-

“Industry Here Feels Stimulus of War Orders,” The Hamilton Spectator, October 20, 1939, https://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/canadawar/hamilton_e.html. ↩

-

Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity,” 7. ↩

-

“Will Tow Unfinished Ships to Hamilton,” The Hamilton Spectator, July 27, 1943, accessed through the Canadian War Museum’s Newspaper Archives. ↩

-

Figure 1: Perry B. Wooster, “HMCS Frontenac at Sea,” Photograph, Halifax, Nova Scotia, accessed March 2022 through the Canadian War Museum Online Archives, https://www.warmuseum.ca/collections/archive/3157507.

“Corvette and Algerine Types to be Brought Here for Equipping of Hulls,” The Hamilton Spectator, June 25, 1943, https://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/canadawar/hamilton_e.html. ↩

-

James S. Pritchard, “Production and Productivity,” in A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilding during the Second World War, 300. ↩

-

Hamilton Port Authority, “Port of Hamilton Celebrates 100 Years, 1912-2012,” https://www.hopaports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Port-of-Hamilton-Celebrates-100-Years-_-book.pdf, 26. ↩

-

Hamilton Port Authority, “Port of Hamilton,” 26. ↩

-

Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity,” 20. ↩

-

James S. Pritchard, “Labour Recruitment, Stability and Morale,” in A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilding during the Second World War, 133. ↩

-

Jack Granatstein, Arming the Nation: Canada's Industrial War Effort 1939-1945 (Canadian Council of Chief Executives, 2005), 8. ↩

-

Granatstein, Industrial War Effort, 8. ↩

-

James S. Pritchard, “Fifty-Six Minesweepers and the Toronto Shipbuilding Company during the Second World War,” The Northern Mariner 16, no. 4 (October 2006): 43, https://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol16/tnm_16_4_29-48.pdf. ↩

-

Figure 2: Caven Ernest Atkins, “Forming Bulkhead Girders,” 1942 Painting, Toronto, accessed March 2022 through the Canadian War Museum Online Archives, https://www.warmuseum.ca/collections/artifact/1013555. ↩

-

Pritchard, “Toronto Shipbuilding Company,” 43. ↩

-

Pritchard,“Labour Recruitment,” 141. ↩

-

Pritchard,“Labour Recruitment,” 142. ↩

-

Pritchard,“Labour Recruitment,” 142. ↩

-

Pritchard, “Toronto Shipbuilding Company,” 41. ↩

-

Chris Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton’s Contribution to the Naval War,” The Northern Mariner 16, no. 1 (January 2006): 32, https://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol16/tnm_16_1-21-52.pdf. ↩

-

Madsen, “Hamilton’s Contribution,” 41. ↩

-

Madsen, “Hamilton’s Contribution,” 45. ↩

-

Pritchard,“Labour Recruitment,” 135. ↩

-

Pritchard,“Labour Recruitment,” 8. ↩

-

Pritchard, “Toronto Shipbuilding Company,” 40. ↩

-

Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity,” 4. ↩

-

Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity,” 32. ↩

-

Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity,” 30. ↩

-

James S. Pritchard, “The Struggle for Steel,” in A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilding during the Second World War, 219. ↩

-

Craig Heron and Robert Storey, “Work and Struggle in the Canadian Steel Industry, 1900-1950, in On the Job: Confronting the Labour Process in Canada, eds. Craig Heron and Robert Storey (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986), 235. ↩

-

Madsen, “Hamilton’s Contribution,” 25. ↩

-

Madsen, “Hamilton’s Contribution,” 31. ↩

-

Heron and Storey, “Work and Struggle,” 235. ↩

-

Madsen, “Hamilton’s Contribution,” 28. ↩

-

Heron and Storey, “Work and Struggle,” 231. ↩

-

“Ontario Board Orders Wage Boosts at Stelco,” The Globe and Mail, Dec 28, 1944. ↩

-

Madsen, “Hamilton’s Contribution,” 30. ↩