Building the Merchant Fleet

The Rise of Wooden Shipbuilding at the Port of Hamilton During the 19th Century

Asher Marcus

Hamilton - 2022

Introduction

Hamilton, ON- an area rich in flora and fauna with stunning beauty, and a gem of nature for Indigenous peoples of the area. The geography of the area made for a prime location for Indigenous peoples early on. The soil was rich and there was a harbour which allowed water and other resources to be easily accessible. Hamilton Harbour was valued by Indigenous peoples for centuries prior to the arrival of French explorer, Étienne Brûlé, in 1616.1 The harbour was officially dubbed Burlington Bay in 1792 and had already gained a reputation for its natural beauty.2 By 1815, the area had been established as a permanent European settlement.3 George Hamilton progressed the area by establishing a village in 1833 which was seven years after the Burlington Canal opened.4 This canal connected Hamilton Harbour to Lake Ontario. Canal workers congregated in the area, and many built themselves ramshackle houses near the bay front– now called the North End.5 These workers led the way for living by the harbour, and eventually had storehouses, barns, and boathouses built to house them and their families.6

These origins help to illustrate how Hamilton and its harbour came to be a permanent location for European settlement in the early 19th century. As the area developed, the demand for shipping increased and connected the harbour to the Great Lakes and later to the Atlantic Ocean which allowed for the Port of Hamilton to be a major part in the development of both the city and the harbour during the 19th century. Prior to the 19th century, there was little shipping in any of the Great Lakes and thus shipbuilding would never have succeeded in Hamilton. The Port of Hamilton was able to develop after the completion of the Burlington Canal, but the emergence of the Great Western Railway made Hamilton into an industrial powerhouse which led to a neglected natural environment in Hamilton Harbour. Larger steamship companies took over the smaller wharves and the port’s shipbuilding activities declined. New technologies and larger conglomerates were the new wave for the industrial powerhouse that the city became, resulting in the 19th century being the opportune time for success in the Port of Hamilton. This topic is vast, and so, this essay will cover the evolution of Hamilton Harbour and the Port of Hamilton through the eyes of shipbuilding in the port. By examining the history of the port, the harbour, and the city, this essay will determine what makes for a good location for shipbuilding, how the Port of Hamilton achieved this during the 19th century, and what changed as the world entered the 20th century.

Hamilton’s History and Port Suitability

The history of Hamilton has been primarily linked to its geographic footprint and key location as a transportation hub.7 The earliest residential and commercial settlements were located near transportation routes. Ancaster and Dundas grew swiftly due to locally built mills and their close proximity to important transportation routes that were established in the early years of Upper Canada.8 Hamilton, however, was significantly behind the region’s other settlements, in terms of development, until the opening of the canal connecting Lake Ontario and Hamilton Harbour.9 Completion of the Burlington Canal allowed for Hamilton to become a lake port, where the transhipment of goods required the building of wharves, warehouses and other dock facilities – all of which created what came to be known as Port Hamilton.10 Hamilton, with a deep harbour and good docking facilities, became the entranceway for goods, people heading west, and became an important location for the export of various products and resources.

At the northern end of James Street, before it became known as the North End, was the area known to all as Port Hamilton.11 In the early 19th century, this area of Hamilton was widely considered a town of its own, with James Street North and John Street providing the only connection to the smaller downtown core in the south. The distinction between the two was so prevalent that the Port of Hamilton pushed for its own bailiff and marketplace in the 1830s.12 It was merchants and landowners that built the first wharves in the area. At this time, incoming goods had to be transported from lake schooners to Durham boats that waited on the other side of the sandstrip that disconnected the area to Lake Ontario. By the mid-19th century, Port Hamilton was humming with activity. At the wharves between MacNab and John Streets, crates were hauled off sailing vessels and steamers into horse-drawn carts on the docks below.13 As time passed, more harbour-related industries emerged along the waterfront, including boatbuilders, sailmakers, and repair shops. Hamilton’s more affluent citizens did not dare to risk going down to these streets, as it was perceived as a rough and dangerous place – the realm of ship carpenters, sailors, chandlers, mechanics and dock workers.14

The focus of the harbour altered with the opening of the Great Western Railway docks and grain elevator in 1854.15 This new business on the eastern shore changed the face of the port entirely by the early 20th century. The freight sheds, coal yards and wharves of R.O. and A.B. MacKay, E. Browne, and Thomas McIllwraith could still be found to the west of James Street North.16 However, the Canada Steamship Lines took on the brunt of the transportation and the wharves left in Port Hamilton were reduced to servicing smaller vessels for families to take across the bay. By the 1940s, many of the original roles of the port had disappeared since wooden boatbuilding could not compete with new materials like fibreglass, and commercial wharves laid vacant.

Shipbuilding Throughout the 19th Century

Hamilton’s 19th century boat builders could produce all types of vessels– from dinghies to canoes to large lake steamers.17 Many of the men employed in this industry were skilled workers and had apprenticed as ship carpenters. At most shipyards, the men worked year-round constructing new boats, with part of the winter spent on repairing and refitting vessels.18 Production varied amongst the shipyards with the Port of Hamilton, as some boatbuilders primarily produced pleasure craft, such as the workers at Bastien’s Shipyard who turned out dinghies, rowboats, canoes, and sailboats.19 Due to smaller boats usually only being of seasonal use, these boatbuilders may have found themselves with less work to do during the winter months. In comparison, shipyards that worked on larger vessels would require lengthier refurbishment and would typically refurbish larger vessels year-round. For example, the Hamilton Bridge and Tool Company at Stuart Street and Caroline Street built numerous large steamers over the course of their existence.20 Large propeller or side-wheel driven steam craft were regularly docked at the Zealand, Robertson, or MacKay shipyards for their winter overhaul.21 These shipyards were quite notable in the Port of Hamilton during the 19th century.

There were many people who set up wharves and shipyards in the Port of Hamilton during the 19th century, some of which have already been identified. One of these individuals was Captain Edward Zealand who had many spectators lining the banks of Zealand’s Wharf when launching ships. One ship built and launched at Zealand’s Wharf was the schooner Hercules, which launched in August of 1863 according to the Hamilton Evening Times.22 Zealand was a prominent fellow within the Hamilton community. He owned several vessels hailing from the Port of Hamilton and was elected commodore of the Hamilton Yacht Club. Zealand’s funeral procession was one of the largest ever seen in Hamilton. Another prominent individual was Aeneas D. MacKay, who erected MacKay’s Wharf in 1864. On the morning of Thursday February 11th, 1864, the following news item appeared in the Daily Spectator:

MacKay's Wharf -Among the many improvements recently effected in this city, there is none likely to confer greater benefits, in proportion to its extent, than the new wharf built by Mr. Aeneas D. MacKay, at the foot of James St. The construction of railways proved highly injurious to the forwarding interests and almost ruined the business; but we are glad to see that the energy of one at least has not been entirely crushed out. His enterprise in erecting a new wharf and warehouses, by far the most extensive and costly in the Province is most commendable, and shows that there are true patriots amongst us still. Mr. MacKay has invested a large amount of money in his new wharf and warehouses; he has no such fears as some of our people have manifested and seems determined to risk his all in an enterprise which we hope will turn out a profitable one.23

Another individual who saw many successful ships built and launched from his shipyard between the 1860s and 1880s was A. M. Robertson. A successful launching took place on April 22, 1873, and the account of the launching appeared in The Hamilton Spectator the next day: “Yesterday afternoon, one of the most successful launches ever witnessed in Hamilton took place at Robertson’s Shipyard. The Columbia was christened yesterday, and the California is expected to be in the water within a month.”24

Prior to and throughout the 19th century, boatbuilding was done by hand with traditional tools, but after the turn of the century, some shipyards began to look like small factories.25 Thomas Jutten’s large workshop at the end of Wellington Street possessed modern woodworking machinery that was powered by electricity and had 35 men working there.26 There was also a fair amount of ship carpenters and machinists that worked for Bastien’s or Askew’s which was another large boatbuilding company in Hamilton.27 Although modern technology was becoming more available, it was still hard to come by for the majority of boatbuilders within the Port of Hamilton. These shipyards would continue to use hand tools all throughout the 19th century, largely due to the availability of timber in the area and the costs of commercial machinery. Although shipyards and their builders operated differently, many of the boatbuilders in Port Hamilton had similar beginnings. It was common for the head boatbuilders to begin their careers as workers such as Henry Bastien who started out as a ship carpenter for the Grand Trunk Railway and eventually became the city’s largest boatbuilder.28 Another example was Thomas Jutten who was an Englishman that began his career as a machine shop operative at the Burrow, Stewart and Milne Foundry on Cannon Street, but later became a boatbuilder and eventually rose to become the Mayor of Hamilton three times.29

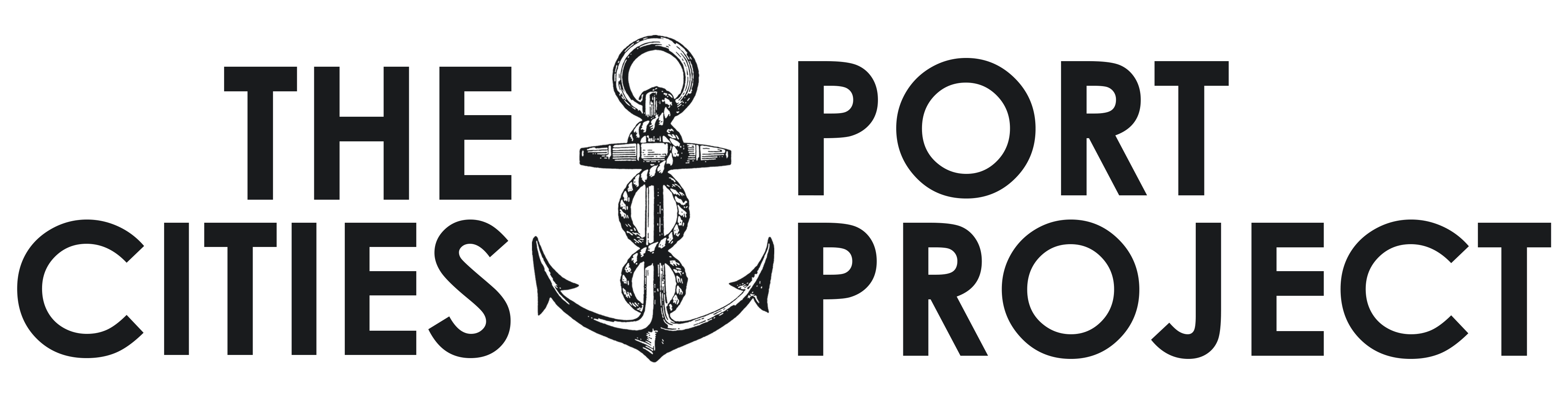

As the decades continued, Hamilton’s shipyards continued production and remained a major part of the city of Hamilton’s physical make-up which garnered documentation of the physical layout of the port. Ivan S. Brookes, who collected photographs and manuscripts of Hamilton Harbour, published a map of the City Docks in 1874. This map (Figure 1) outlines each street leading toward the port and each building located on the port.30

Figure 1

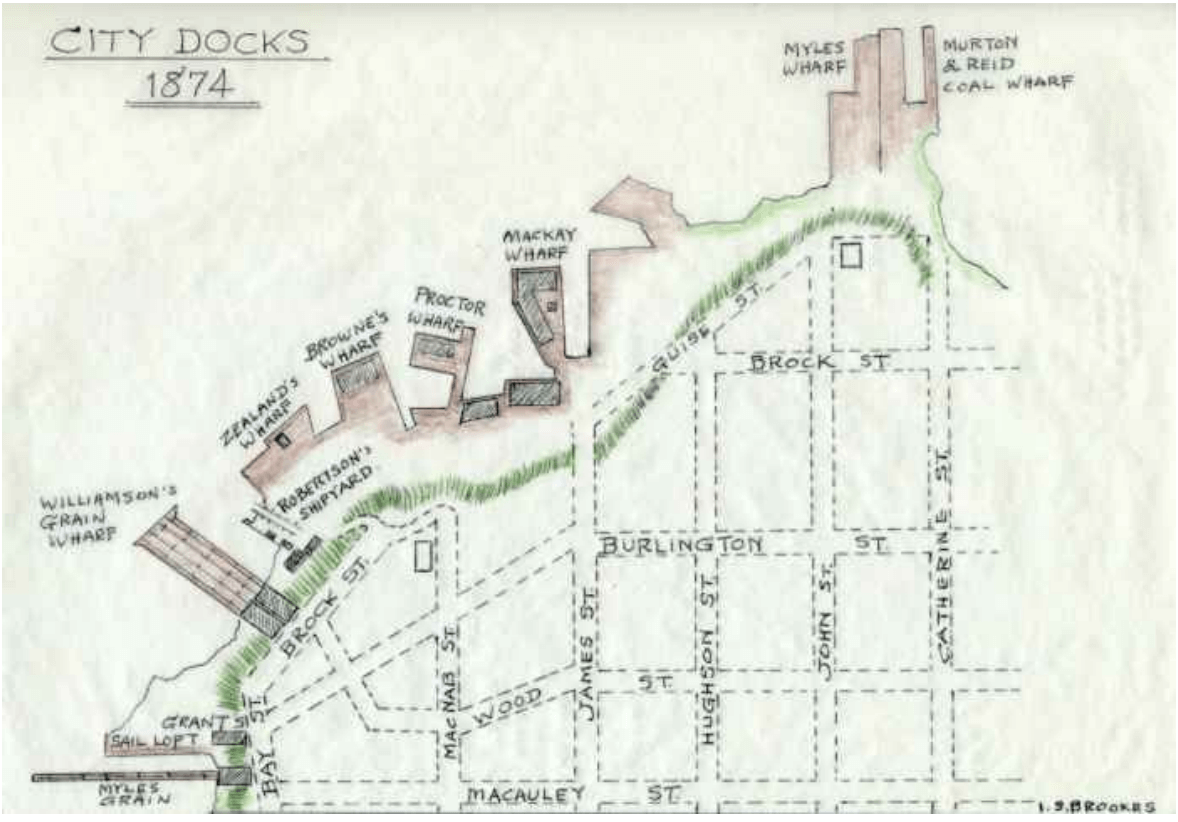

The map identifies Murton & Reid Coal Wharf, Myles Wharf, MacKay Wharf, Proctor Wharf, Browne’s Wharf, Zealand’s Wharf, Robertson’s Shipyard, and Williamson’s Grain Wharf.31 A bird’s eye view drawing of Hamilton from 1876 (Figure 2) features what one can assume to be these same buildings.32 The bottom left part of the map shows the northern side of the city where the Port of Hamilton is located. Along Brock St., Bay St., Nicholas St., Simcoe St., and

Figure 2: Bird's eye view of the City of Hamilton, 1876

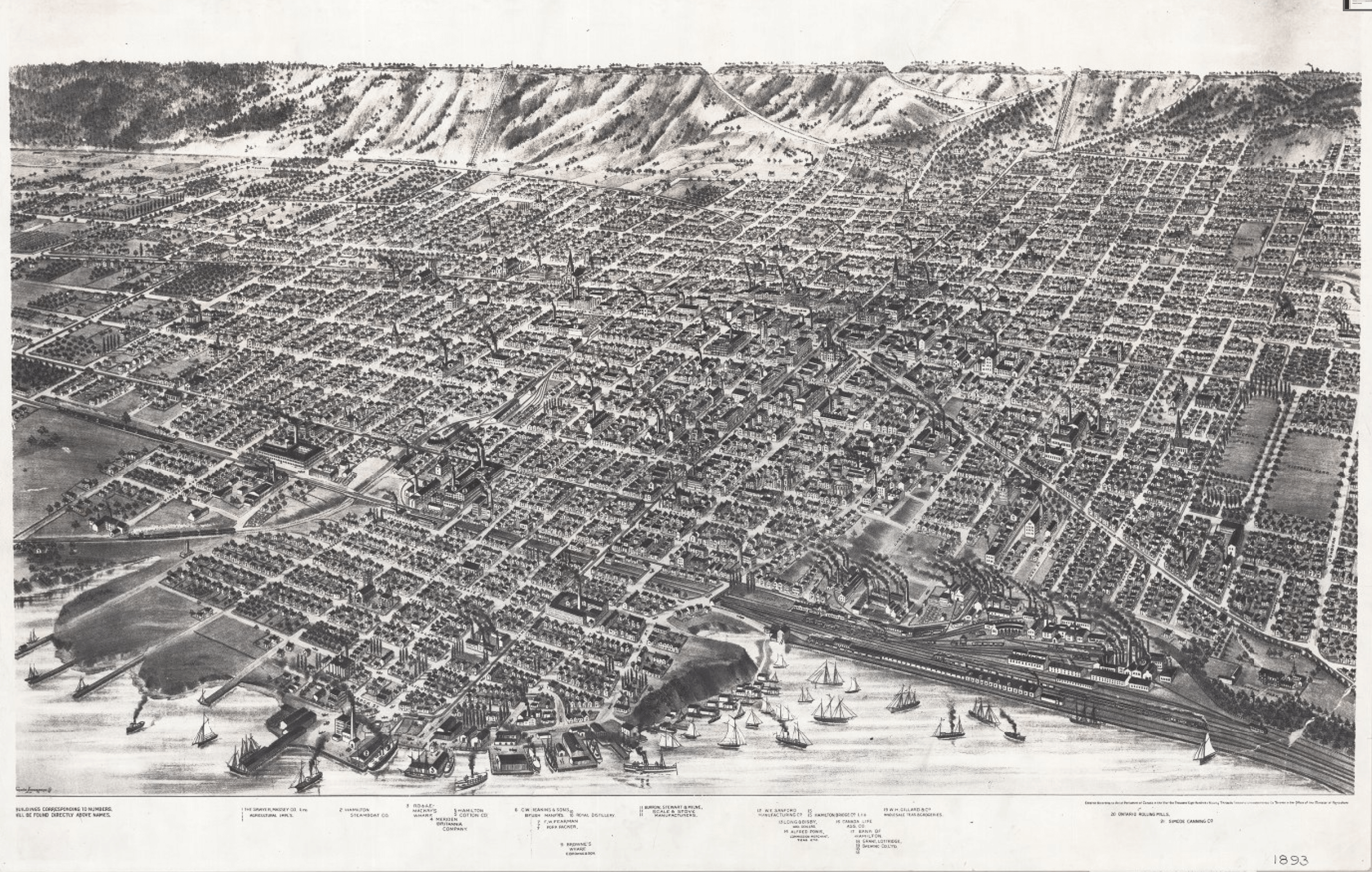

Strachan St. there are various wharves and shipyards that made up the port. This map fails to directly identify these shipyards. In the bottom right of the map, the Great Western Railway is labelled which indicates the significance that the railway had over the shipyards and how these transportation systems were linked. A later drawing of Hamilton from 1893 (see Figure 3) shows that there had been significant changes to the port such as newer steamboat companies taking over where the wharves used to be, reiterating that the Port of Hamilton’s shipbuilding prowess diminished around the late 19th century and into the 20th century, 33 This map does, however, specify some of the wharves and shipyards located at the port, including the Hamilton Steamboat Company, R.O & A.E. MacKay’s Wharf (identified in the bottom left part of the map), and Browne’s Wharf (identified to the right of these wharves). Both maps illustrate the changes done to the Port of Hamilton within twenty years and demonstrates that the Port of Hamilton was a key Great Lakes port with ships docked at the wharves and moving throughout the harbour.

Figure 3: Bird's eye view of the City of Hamilton, 1893

The Suitability of Port Hamilton for Shipbuilding

Understanding the history of Hamilton Harbour and the Port of Hamilton, allows for the identification of how shipbuilding in the port succeeded during the 19th century. For shipbuilding to occur during the 19th century, builders required a wharf and a shipyard. The size of the shipyard needed to accommodate the size of the ships that were being built or repaired there.34 Another key component for successful shipbuilding was the location of the shipyard, as the shipyard needed to be located on the water where vessels could easily move in and out.35 The shipyard also needed to be in a sheltered location to provide protection during the building process, required access to raw materials, like lumber, and have access to modes of transportation to move the goods.36

Hamilton Harbour was not only a suitable location for shipbuilding during the 19th century, but this location remained key to Hamilton’s later role in fitting naval ships during the Second World War. The present-day location remains key to modern ships for loading, unloading and the process of ship breaking as well.

Starting with the completion of the Burlington Canal, Hamilton became a lake port, where the transhipment of cargo required the building of dock facilities, such as wharves and warehouses. The canal opened Hamilton Harbour into Lake Ontario, making the port easily accessible for vessels load and unload. Since the port facilities were located at an inlet of Hamilton Harbour, the port was sheltered from severe weather which would allow for the boatbuilders to work year-round, especially for most shipyards in the Port of Hamilton. Lastly, Hamilton was located in an area with other settlements along creeks that produced lumber mills which allowed for the port to have relatively easy access to raw materials and a means of transporting these resources.

The Port of Hamilton was a suitable and beneficial location for shipbuilding in the 19th century. The completion of the Burlington Canal allowed for the Port to develop and prosper during the 19th century. The emergence of the Great Western Railway transformed Hamilton into an industrial powerhouse, but with larger steamship companies taking over and technological advancements, the city developed a new wave for the industrial powerhouse that it became. Although the business of shipbuilding at the Port of Hamilton would decline by the early 20th century, the development of Hamilton Harbour was enabled and supported by the success of 19th century shipbuilding there and by the early shipbuilders whose skills and abilities supported the trade.

-

City of Hamilton, “Our Harbour, Harbour History,” Hamilton.ca, accessed January 27, 2022, https://www.hamilton.ca/city-initiatives/our-harbour/harbour-history. ↩

-

City of Hamilton, “Harbour History.” ↩

-

City of Hamilton, “Harbour History.” ↩

-

City of Hamilton, “Harbour History.” ↩

-

Bay Area Restoration Council (BARC), “About the Bay,” accessed January 27, 2022, https://hamiltonharbour.ca/about_the_bay. ↩

-

BARC, “About the Bay.” ↩

-

Brian Henley, “Historical Hamilton,” Hamilton Public Library. accessed January 27, 2022, https://www.hpl.ca/articles/historical-hamilton. ↩

-

Henley, “Historical Hamilton.” ↩

-

Henley, “Historical Hamilton.” ↩

-

Henley, “Historical Hamilton.” ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton,” Workers’ City, accessed January 27, 2022, https://www.workerscity.ca/old-port-hamilton. ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

“The Boat Builders,” Workers’ City, accessed January 27, 2022, https://www.workerscity.ca/the-boat-builders. ↩

-

“The Boat Builders.” ↩

-

“The Boat Builders.” ↩

-

“The Boat Builders.” ↩

-

“The Boat Builders.” ↩

-

“The Boat Builders.” ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, MacKay’s Wharf: The story of a shipowning enterprise in Hamilton (1989), 2. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/images/MHGL0001147441T.PDF. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Prosperity for the Shipbuilders: 1873,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/Documents/Brookes/default.asp?id=Y1873&query=trains. ↩

-

Brookes, “Prosperity for the Shipbuilders.” ↩

-

Brookes, “Prosperity for the Shipbuilders.” ↩

-

Brookes, “Prosperity for the Shipbuilders.” ↩

-

Laura Edith Baldwin, The Boat Builders of Hamilton (New Liskeard, ON: White Mountain Publications, 1992), 2. ↩

-

Baldwin, The Boat Builders of Hamilton, 2. ↩

-

Figure 1: Ivan S. Brookes, MacKay’s Wharf: The story of a shipowning enterprise in Hamilton (1989), 7. https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/images/MHGL0001147441T.PDF. ↩

-

Brookes, MacKay’s Wharf, 7. ↩

-

Figure 2: “Bird’s eye view of the City of Hamilton: Province Ontario, Canada” McMaster University’s Digital Archives, J.J. Stoner, 1876, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A70026. ↩

-

Figure 3: “Bird’s eye view of the City of Hamilton: Province Ontario, Canada,” McMaster University’s Digital Archives, Toronto Lithographing Company, 1893, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A82243. ↩

-

“Shipyard Size and Location,” Solr.bccampus.ca, accessed January 27, 2022. ↩

-

“Shipyard Size and Location.” ↩

-

“Shipyard Size and Location.” ↩