The Custom House and Collectors Role at the Port of Buffalo:

The Path to Industrialization throughout the 19th Century

Stacie Morris

Buffalo - 2025

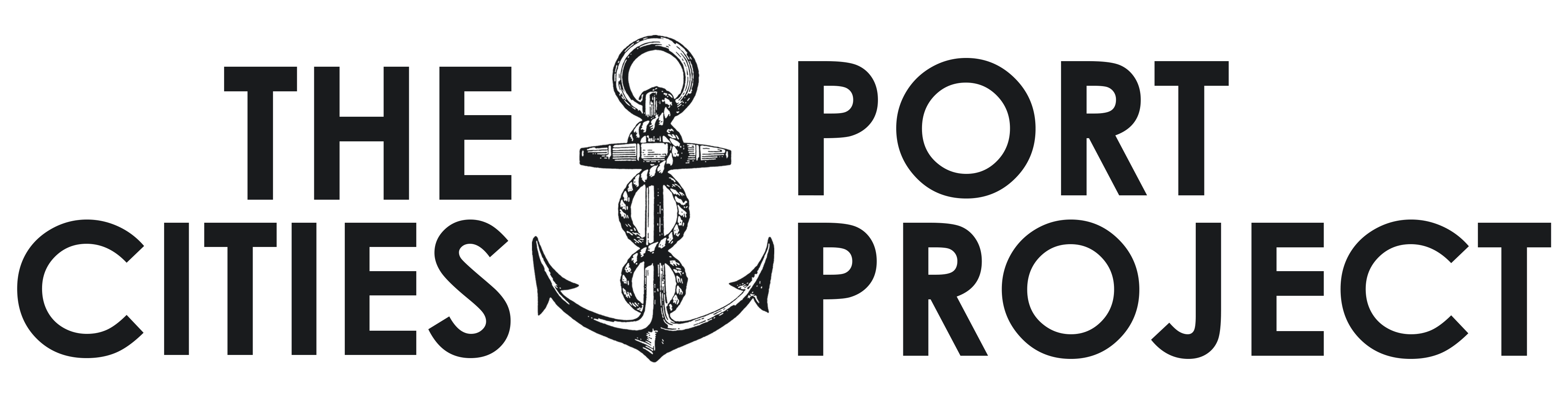

The Port of Buffalo remains a significant location when reflecting on the Great Lakes history of trading, shipping and managing commerce. Before Buffalo became one of the most industrialized ports in Great Lakes history, the port was once used as a ground for wars and battles. Buffalo's transformation into a successful ground for business to succeed on, can be dated back to the region's transformations that took place hundreds of years ago. However, the impact that the 1800s had on the area remains important in understanding the structural changes and advancements that took place to support the port's shipping duties. As the region transformed and evolved during the 19th century, Buffalo began to grow into an industrialized location where shipping and trade could flourish. While shipping duties took place at the Port of Buffalo, customs houses and collectors played a vital role in its function. They have helped bring success to the port through completing a wide range of tasks that helped aid in shipping tasks. To effectively draw attention to the impact of custom houses and collectors at the pit of buffalo, this essay will answer the following research questions: Why were custom houses and collectors so important, how has shipping and trading at the Port of Buffalo impacted Great Lakes history, and what resources and commodities were imported and exported at the Port of Buffalo. Figure 1 illustrates the environment of the Port of Buffalo, before further industrialization and advancements took over.1

Figure 1: 1827 Sketch of Buffalo Harbour.

One of the first major changes that shaped the Port of Buffalo and allowed for custom houses and collectors to aid in shipping duties, was the introduction of a harbour..2 Before development began at the Port, the region surrounding it was occupied with cabins and greenery, as the land was primarily a countryside before the 1800s and many structural changes were needed in order to transform the region into an industrialized location. Prior to the implementation of the new harbour, "no boat larger than a canoe could navigate Buffalo Creek."3 This meant that the creek could not fit any large ships and therefore, shipment and cargo would not be able to navigate its way through Buffalo Creek unless a change was made to the landscape. Creating a harbour allowed for larger ships to pass through the port which would open further opportunities for trade between other businesses along the Great Lakes4.

One of the historic changes that was mandatory to expand opportunities for Buffalo Creek, was the removal of a sandbar that blocked Lake Erie. To take care of this issue, the State of New York decided to grant a loan of $12,000 to complete the construction on the sandbar5. This was good news for the leaders of Buffalo Harbour as the new construction would put an end to many of the flooding and hazards that were persisting because of the sandbars6. The completion of this construction in the early 1820s allowed for the channel to be used by boats, leading to increased shipping activity and eventually, the need for custom houses and collectors to assist in the operations of shipping duties at the Port of Buffalo7.

Over time, as Buffalo began to quickly emerge into one of Great Lakes most successful shipping industries, in 1855, the construction of a Buffalo Custom House took place, taking a year to complete and costing a total of 45,000 dollars.8 This was a huge investment at the time; however, it was an essential building needed to perform various functions at the Port. The custom house was equipped with a basement, and post office packing room, which was useful for storing and preparing shipments efficiently.9

On the other hand, the important duties required of custom house collectors and workers included a floor designated for revenue officials, storage of records, and the courts.10 The revenue workers in the customs house would keep track of the federal taxes on goods and resources. This was a vital role because it ensured that the shipping business was running smoothly, and the government was receiving its share.11 Custom houses at the Port of Buffalo had a major role to play as they "accounted for 86% of federal government revenue from 1789 to 1816."12 Custom house officers kept track of federal taxes on goods and resources, so that the federal government received their share on commodities being exported out of Buffalo and other American states.13 "The custom house was the foundation from which the federal government grew," as custom house officers had to be equipped with financial and organizational skills because of their managerial position.14 They oversaw many vital duties that kept business up and running at the Port of Buffalo. The floors designated for storing paperwork were necessary in keeping track of important documents that would have included information regarding imports, exports, resources, government documents, and business information. Custom houses played a significant role in keeping the flow of business up and running in Buffalo.15

Shipping and trading at the Port of Buffalo impacted Great Lakes history because of its important role in trade and keeping resources flowing, leading to financial growth, and further improvements at the port. As a result of the hard work produced by custom house officers and collectors, the Port of Buffalo was a key player in the grain industry.16 During the 'great maritime grain movement,' Buffalo was the location in which more than 50% of grain stopped before being transported to the Seaboard.17 Buffalo played a crucial role in moving grain across the Great Lakes and to national markets.. Compared to other Great Lakes ports, its infrastructure allowed for grain to be efficiently transported during this major period of movement.18^]^ The Port of Buffalo is uniquely structured because of its fresh water landscape, equipped with connecting rivers that bring together the Buffalo region and East Coast. As a result of this connection, the Port of Buffalo advanced into an international shipping location for commodities such as grain.19 The structure of the lakes surrounding the Port of Buffalo created new opportunities for travel that would allow for resources to make their way to different ports faster and more efficiently.20 The international responsibilities at the port would have benefited the customs offices financially because of the revenue they would have made from ports across different regions.

Custom houses played a role in making sure different states received their grain, along with Canadian territories and other national ports. Grain is an extremely popular, used in items such as bread, pasta, cereal and many other food sources, it was a necessity for many shipping ports. For a total of 44 years receipts have shown that Buffalo has been a prominent factor in the grain train from 1836, having handled a total of 100,000 bushels of grains and this number has been gradually increasing to over one million bushels of grain over the span of 44 years.21 Collectors would have played a major role in producing the yearly reports on the amount of grain traded at the Port of Buffalo. Collectors had to perform various administrative duties, such as keeping records of how much grain was received at Buffalo as this would help track and manage Buffalo's trade during the grain movement.

Another notable factor that shows the importance of the Port of Buffalo in Great Lakes history, is the port's ability to stay successful when locations such as the Welland Canal brought competition. From as early as the 1820s to 1833, when the new Welland Canal was completed, historians have documented the competition that has existed between the Erie and Welland Canal.22 The competition arose because the Erie Canal is located in Buffalo while the Welland Canal is in the Niagara region of Canada and both canals offered shipping ports a great route for transporting goods and commodities. Both canals were prominent for increasing trade during the 1820s, however, competition was evident, as there was a "tendency of American merchants to use the Welland Canal when tolls got too high on the Erie."23 Although this could cause Buffalo to miss out on profit at times, with strategic planning, the Erie Canal continued to help the port with its shipping duties, financial growth and industrialization.24

Figure 2: 1854 Map of Buffalo Harbour.

Figure 2 presents the landscape of the Port of Buffalo, including its ship canal, Buffalo Creek, and large Erie Basin, which leads to the Erie Canal.25 There are five arrows on the map which indicate important features of the Port of Buffalo. The shipping canal was used by incoming ships at the port and upon their arrival, collectors would have to be ready to unload these ships and prepare for regular shipping duties. The Erie Basin, located on the right side of the map, shows a large body of water with two passages leading to the Erie Canal.26 With the convenience of the Erie Canal, trade and business thrived, necessitating the management of expenses and finances by custom houses.

Lastly, custom houses and collectors operated as a business therefore, many different imports and exports were handled and rules enforced by custom house officers. Some of the popular imports brought into the Port of Buffalo included, barely, corn, canned goods, flaxseed, lumber, oats, shingles, and wheat.27 Each import reached over a million in quantity due to their high demand within the region. Grain for example, was under a requirement to be inspected.28 Collectors would have conducted these inspections by organizing the grain materials monthly while exports were commonly done using elevators and railroads.29 Many of the different exports transported across the lake included coal, cement, salt, sugar, and other goods.30 Custom house collectors often recorded information on imports and exports to keep track of the commodities that were in demand. It is stated that these documents were often "collected from the clearances" and "issued during the season of navigation."31

Custom houses and collectors had to keep track of the costs of using the grain elevator as there was a fee of one cent per bushel, which was applied to bushels of grain that used the elevator and storage amenities for a 10 day period.32 While one cent per bushel may seem relatively low, when analysing this fee from a modern day perspective, the excessive amount of grain handling at the Port of Buffalo would have quickly accumulated charges that custom houses would have had to manage. When it came to running a business, custom house officers had a duty to not only manage profits but also the outflow of income, which was crucial to the success of the Port.33

Custom house collectors often had to abide by various rules when managing commodities. For example, during the early 1900s, historical evidence has shown that certain hours were set in which cargo could be cleared however, these rules differed for foreign shipments.34 For example, daytime hours at the Port of Buffalo were strictly set when handling cargo from foreign locations.35 It is stated that "foreign cargo may be loaded or discharged only between 8 a.m. and 5p.m., except by special permit."36 Domestic goods could be handled at any time however, foreign shipments had to be strictly regulated for security purposes, as it is coming from international locations.37 Along with managing imports and exports, watching out for smuggling activities was a mandatory duty. Newspapers in the early 19th century often reported smuggling attempts that would take place at the Port of Buffalo.38 People would attempt to smuggle different products across the Port of Buffalo and officers working at the custom house would have to seize these goods.39

Figure 3: Shipping on the Buffalo River.

Figure 3 depicts the environment of the Port of Buffalo around the 1890s. The location was quite industrialised at this time and equipped with amenities such as the grain elevator which is in the right circle. This building is called the 'Wheeler grain elevator,' which was used by

custom houses and collectors to sort grain.40

When reflecting on the importance of custom houses and collectors, the impact that shipping and trading at the Port of Buffalo has left on Great Lakes history, and the managing of imports and exports, it can be understood that custom houses and collectors at the Port of Buffalo remain a recognizable figure in Great Lakes history. Through their hard efforts and skills, the Port of Buffalo has had the opportunity to transform into an industrialised shipping port today, and shipping ports internationally, have all benefited from the work produced by custom houses and collectors at the Port of Buffalo. Without these vital roles, the port would not be where it is today.

-

Figure 1: [1827 Sketch of Buffalo Harbor], illustration, New York Heritage digital collections, 1829. ↩

-

Robert Holder, The Beginnings of Buffalo Industry, Buffalo, New York: Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society, 1960), 2. ↩

-

Holder, "The Beginnings," 2. ↩

-

Holder, "The Beginnings," 2. ↩

-

Holder, "The Beginnings," 2. ↩

-

Jennifer Walkowski, Historic Resources of the Black Rock Planning Neighbourhood (Buffalo, New York: Clinton Brown Company Architecture, 2010), 7. ↩

-

Walkowski, "Historic Resources," 8. ↩

-

Susan R. Slade, United States Customhouse (Buffalo, New York: National Park Service, 1973), 3. ↩

-

Slade, "United States Customhouse," 3. ↩

-

Slade, "United States Customhouse," 3. ↩

-

Matthew Lively, Historical Custom and the Custom House: How Custom House Governance from 1789 to the Early 1800s Contradicts a Strong Nondelegation Doctrine, The University of Chicago Business Law Review (2024). ↩

-

Lively, "Historical Custom and Custom House." ↩

-

Lively, "Historical Custom and Custom House." ↩

-

Lively, "Historical Custom and Custom House." ↩

-

Lively, "Historical Custom and Custom House." ↩

-

Robert W. Elmes, The Great Lakes Grain Movement Buffalo and the St. Lawrence Shipway (Buffalo New York: Buffalo Chamber of Commerce, 1929), 4. ↩

-

Elmes, "The Great Lakes Grain Movement," 4. ↩

-

Elmes, "The Great Lakes Grain Movement," 4. ↩

-

TJ Pignataro, "The Buffalo River's Comeback," New York State Conversationalist 76, no.4 (2022), 12. ↩

-

Pignataro, "The Buffalo River's Comeback," 12. ↩

-

W.H Howells, Commerce, Manufacturers and Resources of Buffalo and Environs (Buffalo, New York: Commercial Publishing Company Limited, 1880),19-20. ↩

-

Janet D. Larkin, "The Canal Era: A Study of the Original Erie and Welland Canals within the Niagara Borderland," American Review of Canadian Studies 24, no. 3 (1994), 1. ↩

-

Larkin, "The Canal Era," 1. ↩

-

Larkin, "The Canal Era," 1-2. ↩

-

Figure 2: [1854 Map of Buffalo Harbor], map, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, National Archives Catalog (1854). ↩

-

Author Unknown, Map of the Buffalo Harbor New York, Records of the Office of the Chief Engineers, National Archives Catalog (1854). ↩

-

Author Unknown, Statistics of the Trade and Commerce of Buffalo 1909-1910 (Buffalo, NY: Chamber of Commerce and Manufacturers Club, 1911), 5. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Statistics of the Trade and Commerce," 18. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Statistics of the Trade and Commerce," 18. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Statistics of the Trade and Commerce," 25. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Statistics of the Trade and Commerce," 25. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Statistics of the Trade and Commerce," 10. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Statistics of the Trade and Commerce," 10. ↩

-

Author Unknown, The Port of Buffalo, N.Y (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Press, 1931), 13. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "The Port of Buffalo," 13. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "The Port of Buffalo," 13. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "The Port of Buffalo," 13. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Buffalo, Jan. 19," The Evening Post (1812). ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Buffalo, Jan. 19." ↩

-

Figure 3: [Picture of Ships on the Buffalo River], photograph, New York Heritage digital collections, ca. 1890-1910. ↩