Immigration in 19th Century Buffalo:

Opportunities and Struggles

Skyler Solodiuk

Buffalo - 2025

In the 19th century, Buffalo, New York, emerged as a key destination for European immigrants in search of a better life and greater economic opportunity. Known today for its industrial legacy and proximity to the Canadian border, the city's history is deeply intertwined with waves of immigrants who passed through its port. This essay explores the impact of immigration on Buffalo's economic and social development, the role of the Erie Canal in shaping immigration, the experiences of different immigrant groups, and the challenges they faced in an evolving industrial city. Key questions addressed include: How did Buffalo's geographical location and the Erie Canal contribute to its role as an immigrant gateway? What were the main immigrant groups that settled in Buffalo, and what economic opportunities and hardships did they encounter? By examining these questions, this essay will highlight both the opportunities and struggles that defined the immigrant experience in Buffalo during the 19th century.

Historically, the city of Buffalo was once a vast bustling and flourishing Great Lakes port city and had an extensive maritime past. The city became constitutionally established in 1804, mainly emerging due to its distinct and unique geographical location, which would serve several advantages and purposes for building up the city. Located on the eastern shore of Lake Erie at the mouth of the Niagara River, the port of Buffalo provided direct access to both the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean through the St. Lawrence Seaway; it was an essential route for connecting the East Coast to the Midwest.1

Buffalo's strategic location at the western terminus of the Erie Canal earned it the title of "The Gateway to the West." It became a pivotal departure point for European immigrants heading toward the American heartland, particularly those travelling through the city on their way to settle in the Midwest.2 Once in Buffalo, many continued their journey westward via the Erie Canal or railroads, seeking opportunities to farm and build new lives. Others chose to stay in Buffalo, as the rise of industrial jobs began to attract workers to the city.

The Erie Canal, often called the "Mother of Cities," was instrumental in Buffalo's growth.3 Stretching 363 miles, it connected the Hudson River to Lake Erie, with boats ascending nearly 600 feet through 35 locks. Between 1834 and 1862, the canal was expanded and deepened through a series of improvement projects led by the New York State Canal Commissioners and overseen by the New York State government, transforming it into a vital trade route connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, the Midwest, and the Southern states. 4 This transformation spurred economic growth, industrial expansion, and agricultural development in Buffalo, drawing in immigrants from around the world, through the numerous job opportunities it provided in construction, manufacturing, grain milling, and steel production.5 After its completion in 1825, the canal played a central role in the surge of immigration throughout the 19th century.

Additionally, the establishment of railroads, starting with the New York Central along the Erie Canal route, was pivotal in Buffalo's industrial growth. The railroads connected the city to key markets, including Chicago and New York City, and created a network that fuelled significant developments of industry around these rail lines as well as along the Canal and the Buffalo River.6 This played a foundational role in providing jobs and fostering industrial growth, transforming Buffalo into a bustling manufacturing centre, and making it attractive to immigrants in search of employment opportunities.

New York state has long been a major hub of immigration activity and entry, particularly due to the largest port of Ellis Island. In the early days of immigration, immigrants arriving via the New York harbour, were able to travel to Buffalo, through the Erie Canal, arriving at the Buffalo port.7 Additionally, Buffalo's proximity to Canada made it an accessible entry point for many immigrants. In the late 18th century immigration began to boom in the state, with immigrants fleeing their homelands and making a route to America, after facing a variety of hardships. Many immigrants came fleeing crop failure, poverty, land and job shortages, political unrest and persecution. For many Irish immigrants they came fleeing famine, and for Jewish immigrants, religious persecution throughout Europe.8

America was seen as a land of opportunity, and Buffalo quickly became a prime destination for those looking to build new lives and achieve the American dream. The city's growing industrial and commercial sectors played a crucial role in this transformation. After the Erie Canal was completed, Buffalo's economy soared, solidifying its position as a vital transportation hub and its canal harbour becoming a vital entry point for immigrants arriving by ship, as illustrated below in figure 1.9

Figure 1: The Canal Harbour, Port of Buffalo.

Immigration in Buffalo began to soar in the 1840s, with the city's population growing from 29,773 in 1845 to 74,214 by 1855. By that year, more than 60% of Buffalo's residents were foreign-born.10 The first major wave of immigration was largely from Germany, with approximately 31,000 Germans settling in the city. Many were skilled workers who found jobs as masons, boilermakers, and blacksmiths.11Alongside them, approximately 18,000 Irish immigrants arrived, seeking employment in various industries, including shipping, construction, and, notably, in the grain elevators along the Buffalo River. The Irish settled in the First Ward, while Germans concentrated on the East Side, with each group forming their own communities, schools, and churches.12

In 1870, Buffalo saw a third major wave of immigration, this time from Polish and Italian immigrants, which caused the city's population to triple.13 Many Polish immigrants came seeking better opportunities, fleeing economic hardship, and poor living conditions in their homeland. Polish immigrants found jobs in railroad yards, foundries, construction sites, and tanneries.14 It is estimated that by the end of 1892, 26,000 Polish immigrants resided in Buffalo, primarily settling in East Side neighbourhoods.15 Similarly, Italians arrived in large numbers, fleeing drought, crop failure, heavy taxation, and political instability. They primarily settled on Buffalo's West Side and downtown, finding employment in heavy labour industries such as docks, construction, and factories, as well as seasonal work like canning and farming.16

Between 1870 and 1900, Buffalo experienced its fourth major wave of immigration, this time from Black families leaving the rural South during the Great Migration. The Great Migration was one of the largest mass movements in American history, in which African American families left the rural South, fleeing enslavement, and in search for freedom, work, and opportunity, in Northern states, attracted by the abundant industrial employment opportunities, which Buffalo had to offer.17 At the peak of the Great Migration, 4,000 Black migrants arrived in Buffalo. Over the next ten years, that number more than doubled, with many settling primarily on the East Side of the city.18 Figure 2 illustrates key wards like the First Ward and the West and East sides, historically home to large immigrant populations.19 This flow of migration highlights just how significantly Buffalo was viewed as a symbol of freedom, opportunity, and a better life.

Figure 2: Map of Buffalo, Highlighting Neighbourhood Wards, 1893.

By 1900, three-quarters of Buffalo's population was foreign-born. The city grew by roughly 38% between 1890 and 1900, becoming the 8th largest city in the U.S. and the 6th busiest port in the world, with a population of 352,387.20 While Buffalo presented numerous opportunities for those seeking a better life, the path was not without its struggles. Many immigrants faced significant hardships, including harsh working conditions, exploitation, educational disadvantages, child labour, discrimination and legal segregation, and the challenge of adapting to a society that was often unwelcoming and divided by race and religion.

Although many immigrants found work in Buffalo's booming factories and industries during America's industrialization, particularly in construction, manufacturing, shipping, transportation, and more, these opportunities came with harsh realities. Workers were regularly required to labour long hours, 10 to 12 hours a day, under unsafe conditions, exposed to toxic chemicals and the constant risk of accidents. Moreover, tasks were frequently divided into repetitive, monotonous duties aimed at maximizing efficiency, which made the work both physically exhausting and mentally draining, all for very low wages.21 While these jobs were essential for survival for these immigrants, it came at the cost of their health, safety, and well-being.

Child labour was a harsh reality for many immigrant families in Buffalo during the late 19th century. As the city's population grew, so did the demand for consumer goods, which in turn fuelled the need for labour. This rising demand led to a significant number of children, particularly from immigrant communities facing poverty and limited educational opportunities, entering the workforce. They found employment in various industries, including agriculture, canning factories, textile mills, plumbing, bricklaying, and glass working.22 Many of these children were forced to forgo free public education to contribute to their family's financial survival. By the 1880s, child labour in New York State was widespread, with estimates ranging from 60,000 to over 200,000 children employed in various sectors, and Buffalo emerging as a major hub for this.23

Due to Buffalo's growing immigrant population, by 1900, nearly three-quarters of the student body was made up of immigrants or their children. As a result, public schools became overcrowded, with up to 100 children per teacher. Conditions were poor, with inadequate lighting, ventilation, sanitation, seating, and a lack of proper textbooks.24 Despite efforts to reform the system, many policy makers believed immigrant children were better suited for manual labour than intellectual pursuits, leading to a curriculum focused on vocational training. Consequently, many immigrant children dropped out of school to work and never advanced beyond elementary education.25 This lack of quality education limited their economic mobility, contributing to poverty and social and economic disadvantages for immigrant families.

Employers frequently took advantage of immigrants, often referring to them as "greenhorns," knowing that many had fled difficult circumstances in their homelands, immigrants were easier to exploit.26 These immigrants were typically assigned the most menial and physically demanding jobs, earning lower wages than native-born workers. During off-peak seasons or times of economic slowdown, workers were often laid off without any compensation, leaving them vulnerable and without financial security. Additionally, if any worker raised concerns about their wages, long hours, or unsafe conditions, they risked being blacklisted and labelled as troublemakers, making it incredibly difficult to find work elsewhere.27 This exploitation not only perpetuated economic inequality but also highlighted the harsh realities many immigrants faced as they struggled to earn a living, in a city that took advantage of their vulnerability.

As Irish and Italian Catholics settled in Buffalo, their strong cultural and religious identities often clashed with the city's predominantly Protestant population. Tensions between Protestant nativists and Catholic immigrants led to conflict in Buffalo, with individuals like Reverend J.G. Lord spearheading attacks on Catholic institutions like the Sisters of Charity Hospital, accusing them of trying to convert Protestant children.28 The divide deepened with the visit of Allessandro Gavazzi, a former priest turned critic of the Catholic Church, whose lectures in Buffalo went against the pope and church, which fuelled further animosity throughout the city.29 Many attacks on Catholic individuals, like Catholic Bishop Timon, would be published by the Buffalo Gazette, further increasing hateful views toward Catholicism.30 Like many mid-19th century cities, Buffalo was deeply affected by nativist, anti-Catholic sentiment and religious-political struggles related to immigration.

Many Italian immigrants in Buffalo faced persistent discrimination due to their ethnicity, which deeply impacted their experiences in the city. By the mid-1880s, a distinct Italian community, known as "Little Italy," emerged on Buffalo's West Side. While this enclave fostered cultural solidarity, it also reinforced residential segregation, limiting Italians' integration into the broader social and economic spheres.31 This area was often referred to as a "slum,"32 with Italians stereotyped as violent, unkempt, and mobsters.33 Access to higher education was also scarce for Italian immigrants, further limiting their opportunities for professional advancement. Consequently, around 62% of Italian immigrants worked as seasonal labourers and had little representation in fields like law, medicine, and politics.34

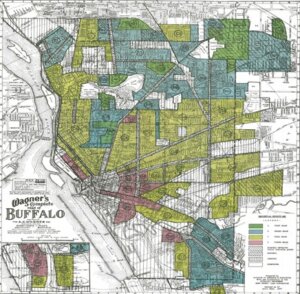

African American migrants in Buffalo faced significant challenges due to systemic racism, which severely limited their opportunities across various aspects of life. Discriminatory practices such as redlining, white flight, and blockbusting created significant barriers. As Black families began settling in predominantly white neighbourhoods like South Buffalo, racial tensions escalated, with many white residents fearing that their property values would "depreciate".35 White homeowners took advantage of this anxiety, selling properties to Black families at inflated prices, while redlining denied them access to mortgages. Figure 3 illustrates redlining in Buffalo, where the red blocks indicate Black neighbourhoods.36 These policies deepened the racial and economic divide, with the Black population in South Buffalo increasing as wealthier white residents moved North, segregating the city.37

Figure 3: Redlining Map of Buffalo, 1937.

In conclusion, Buffalo's history of immigration is a story of both opportunity and struggle. The city's geographical location, the construction of the Erie Canal, and the rise of industrialization made it a prime destination for immigrants seeking a better life. However, the harsh working conditions, educational barriers, and discrimination many immigrants faced underscore the challenges of building a new life in an industrializing America. Despite these hardships, immigrants contributed immeasurably to Buffalo's growth, shaping its economy, culture, and social fabric. The immigrant experience in Buffalo serves as a testament to the resilience of those who sought a better future in a land of opportunity, and it remains a powerful reminder of the ongoing struggles for equity and inclusion in urban America today.

-

Author Unknown, The History of Buffalo, NY, 2024. ↩

-

"Buffalo History", Visit Buffalo Niagara, n.d. ↩

-

Author Unknown, History and Culture, Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor, n.d. ↩

-

Thomas P. DiNapoli, The Erie Canal: Celebrating 200 Years of a National Landmark, Office of the New York State Comptroller, n.d. ↩

-

Unknown Author, The History of Buffalo, N.Y. ↩

-

John Henry Schlegel, Like Crabs in a Barrel: Economy, History and Redevelopment in Buffalo, University at Buffalo Center for Studies in American Culture (2005), 6. ↩

-

Dana L. Saylor, "A Timeline of Immigration in Buffalo," Buffalo Spree, (2020), Para. 18. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Immigration to the United States, 1851-1900, Library of Congress (n.d). Para. 1. ↩

-

Figure 1: Jeff Z. Klein, "Buffalo's Vanished Maritime Past," Belt Magazine, Jul. 9, 2020. ↩

-

Mark Goldman, High Hopes: The Rise and Decline of Buffalo, New York (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983), 72. ↩

-

Goldman, "High Hopes," 3. ↩

-

James Napora, Houses of Worship: A Guide to the Religious Architecture of Buffalo, New York. Buffalo Central Library (n.d), 415-416, 437; Anthony Cardinale, "Ethnic Heritage Enriches Buffalo," The Buffalo News, Oct.12 1980. ↩

-

Janet C. Fehskens, History of Buffalo Immigration and Southeast Asian Connection: March 7, The Daily Bulletin, Buffalo State University, Mar. 4, 2016. ↩

-

Eugene Obidinski, "Polish Americans in Buffalo: The Transformation of an Ethnic Subcommunity," The Polish Review 14, no. 1 (1969), 31. ↩

-

Obidinski, "Polish Americans in Buffalo," 30. ↩

-

Chuck LaChiusa, History of Italian-American's in Buffalo, NY, History of Buffalo (1985). ↩

-

Stewart E. Tolnay, "The African 'Great Migration' and Beyond," Annual Review of Sociology 29 (2003), 210. ↩

-

Anna Blatto, A City Divided: A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo, Open Buffalo (2018), 6. ↩

-

Figure 2: [Map of Buffalo, Highlighting Neighbourhood Wards, 1893] map, G.M Hopkins & Co, WardMaps LLC (1893). ↩

-

Author Unknown, Buffalo Timeline, National Park Service (2012). ↩

-

Author Unknown, "America at Work" America at Work, America at Leisure: Motion Pictures from 1894 to 1915, Library of Congress, n.d. ↩

-

Richard B. Bernstein, From Forge to Fast Food: A History of Child Labor in New York State. Volume II: Civil War to the Present, New York Labor Legacy Project (Albany: The University of New York, 1995, 3. ↩

-

Bernstein, "From Forge to Fast Food," 3. ↩

-

Maxine Seller, "The Education of Immigrant Children in Buffalo, New York 1890-1916," New York History 57, no. 2 (April 1976), 183--99. ↩

-

Seller, "The Education of Immigrant Children," 188. ↩

-

Unknown Author, Working Conditions, New York Heritage Digital Collections (n.d). ↩

-

Unknown Author, "Working Conditions." ↩

-

M. Felicity O'Driscoll, "Political Nativism in Buffalo, 1830-1860," Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 48, no.3 (September, 1937). 295. ↩

-

O'Driscoll, "Political Nativism in Buffalo," 299. ↩

-

O'Driscoll, "Political Nativism in Buffalo," 289. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Immigrant Communities of Buffalo and the Pan-American Exposition of 1901, State University of New York at Buffalo, University Libraries (2001),9. ↩

-

Giuseppe Piccoli, "Italian Immigration in the United States," Duquesne Scholarship Collection (2014), 29. ↩

-

Piccoli, "Italian Immigration in the United States," 31. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Immigrant Communities," 9. ↩

-

James Coughlin, "City of Redlined Neighbourhoods: Redlining in Past and Present Buffalo," Peace Chronicle (2024), 12. ↩

-

Figure 3: [Redlining Map of Buffalo, 1937], map, Denise Lynn, "Mapping Inequality, Redlining in New Deal America." ↩

-

Unknown Author, Redlining: How Racial Discrimination Hobbled Black Homeownership in Buffalo, WKBW (2021). ↩