Battle of Black Rock:

Warfare on the Niagara Frontier: The Battle of Black Rock

Nolan Whitworth

Buffalo - 2025

On the night of December 29th, 1813, a large detachment of British soldiers led by Major General Phineas Riall crossed the Niagara River and descended upon the town of Black Rock. Black Rock was among the many strategic towns dotted along the turbulent Niagara frontier. British forces sought to ravage this unassuming New York town and its surroundings as an act of revenge for recent American atrocities committed against Canadian civilians. The battle was a total victory for the British, and in the aftermath, both Black Rock and Buffalo were devastated by fires and looting. The British managed to take the field due to their tactical genius and use of unconventional tactics. This paper will examine the Battle of Black Rock in its entirety examining the prelude, the course of the battle, and the grizzly aftermath. By using the bloody attack on Black Rock as an exemplar, this essay will highlight key tactics, strategies, and realities of warfare along the Niagara frontier during the War of 1812.

Black Rock and the Niagara Frontier

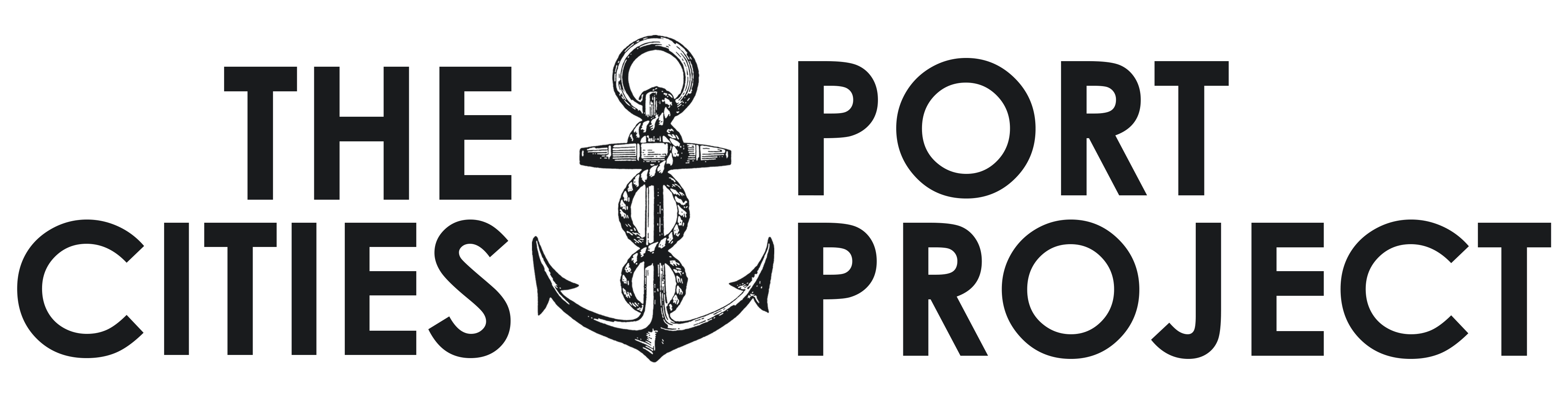

The Niagara Frontier is a 58km long chokepoint in the Great Lakes region that separates Canada and the USA with the natural border of the Niagara River. This strategic region stood (and still does) as an important point of movement and trade in North America as travelers could bypass Niagara Falls and portage between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. It is of no surprise that both sides of the conflict sought to control this valuable territory as by holding it they could easily supply and reinforce these two vastly different theatres of war.1 On both sides of the river, many fortresses such as the soon-to-be-mentioned Fort George were erected at the Northern and Southern entry points. Some were even built at portage depots such as Fort Chippewa. Built originally to oversee and aid in colonial trade activity, these forts were now strategic strongholds along this frontier. Though it was not a fort, the town of Black Rock was still an important site in the war due to its position and formidable shipyard. Figure 1 is a contemporary map of the southern mouth of the Niagara River. Note Black Rock's strategic harbour location on the Eastern shore.2 Some of the very ships commanded by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry at the decisive naval engagement of Lake Erie were prepared at this very port.3 It was noted by American Lieutenant Jesse Duncan Elliot that if it weren't for Black Rock's proximity to British artillery, this deepwater port would have been one of the principal ports in Lake Erie's ship-building operations.4

Figure 1: Map of the Upper Niagara River,1820.

Prelude to Battle

By the winter of 1813, land warfare operations in the Niagara region had been somewhat inconclusive. Both sides had inflicted considerable losses on each other at various engagements such as at the famed battle of Queenston Heights. However, few significant land gains were made. At the time the Americans did have the upper hand as they occupied the town of Newark (modern Niagara-on-the-Lake) along with its fortress, Fort George. Though the Americans currently held the land, the garrison was vastly undermanned with only about 100 troopers. British forces were also beginning to build up in the region. The fort's commander, Brigadier General George McClure was horrified by the very likely possibility of a British assault. On December 10th, 1813, McClure did the unthinkable and torched the entirety of Newark (along with the fort) then retreated across the river. McClure gave little warning to the around 400 citizens who were mostly women and children; many would die homeless in the cold Canadian weather.5 In the age of "gentlemanly" and honorable warfare a move such as this was shocking. This senseless act had to be repaid. Lt. Gen. Gordon Drummond, the newly appointed Lt. Governor of Upper Canada called upon Major General Phineas Riall to take revenge against McClure.6 A native-born Irishman, Riall received much acclaim for his brave deeds on the Niagara frontier and would be knighted in 1833. Figure 3 offers a contemporary portrait of the Major General.7 British vengeance was immediate, with Fort Niagara being taken just 8 days later by Colonel John Murray. Riall then commenced a fierce march south, burning the settlements of Youngstown, Manchester, Tuscarora, and Lewiston as well as the fortification at Schlosser's landing (an American portage entrance).8 His march was halted by a sabotaged bridge, but Riall would soon be back to finish his march south. One contemporary newspaper commented on the pillaging situation stating, "It was expected that Buffalo would momentarily share the same fate".9

Figure 2: A contemporary portrait of Major General Phineas Riall by an unknown artist, c. 1815.

The Battle of Black Rock

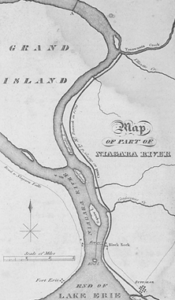

On the evening of December 29th, the Battle of Black Rock began. The operation would involve a two-pronged assault, beginning with a landing led by Riall , three kilometers north of the town at modern Amherst and Niagara Street (Buffalo). About an hour later a detachment led by Lieutenant Colonel John Gordon would cross the river and directly assault Black Rock to divert enemy attention away from the main force and create confusion.10 These two landing points are highlighted with red markers in Figure 4.11 This was a rather daring operation as Black Rock was a decently fortified location. It held strategic importance to the Americans, and they had no intention of giving it up even if the enemy outnumbered them. Small wooden boats were easy targets for artillery crews, and their only real protection was a thunderous counter barrage from the other side of the river. Striking at night was more optimal for the English as it gave them the element of surprise.12

Under Riall and Gordon's command was a mixed force of 965 British regulars and 50 Canadian militiamen. Attached to the regulars was a five-gun battery situated on the adjacent shore (for covering fire) and a force of around 400 Indigenous warriors.13 Having these warriors join the raiding force was a wise decision on Riall's part as not only were

Figure 3: 1813 map of Black Rock, note the landing points (red arrows) and numbered landmarks.

they skilled in unconventional forest warfare/navigation, but they also inflicted great psychological terror on the Americans. Longstanding colonial views toward Indigenous populations painted these warriors as horrifying, godless savages. These fears would only be accelerated by defamatory articles in newspapers that highlighted their fearful battlefield practices, such as scalping.14 In an address to American locals made on the day of the first British crossing, the disgraced general George McClure would play on the public's fear of the natives to rally the people to bear arms. In his address, he stated, "should they be suffered to penetrate into the interior with their savages, the scene will be horrid."15 This widespread fear of the Indigenous population would have no doubt given the British a psychological advantage over their enemy. When American forces did eventually retreat, many of these men likely did this as they feared what the Indigenous peoples would do to them and their defenseless families back home in Black Rock and Buffalo. Their loud war whoops and their guerilla style of combat (as opposed to the standard British line infantry formation) would have been a fearful sight indeed for an American militia man.

The first contact would take place near Scajaquada Creek where British regulars easily captured the sailor's battery (point 9 on the Black Rock map).16 After hearing the news of their landing, Major General Amos Hall, who was in command of some 2000 militia, attempted to reinforce this front. The fighting was violent and confusing. American forces were disoriented by the darkness that night brought and faced difficulty in pushing back their well-drilled enemy. After sending in two detachments of militia, British lines still hadn't budged, so Hall personally took command and led his remaining forces stationed in Buffalo to reinforce Black Rock.17 At the break of dawn, the second wave of the British raiding party led by Gordon began to trickle ashore near General Porter's House (point 17 on the Black Rock map). The riverside was filled with the sounds of cannon fire as both batteries let off unrelenting barrages at their foes. Gordon took considerable losses from the cannonade in this frontal assault with three of his boats grounding. In his post-battle report, Riall noted he was still satisfied with Gordon's leadership as the incident was an accident.18 The use of grapeshot, unleashed by the American batteries, was especially devastating to these small wooden ships. Figure 4 is a 24-pounder artillery piece that was used in the War of 1812.19 This size of cannon (used at Black Rock) was commonly used in defensive coastal batteries and onboard heavy vessels of war. Though Gordon's attack was less than satisfactory, it diverted American artillery away from Riall and the main body of troops. In the meantime, on the right flank, American numbers were slowly deteriorating, and Hall would eventually call for a full retreat to Buffalo. In Major General Amos Hall's after-action report, he states that "after standing their ground (American Militia) for half an hour, opposed by an overwhelming force, and nearly surrounded, a retreat became necessary to their safety and was accordingly ordered."20

Figure 4: A 24-pounder cannon used in the War of 1812, currently in a park in Hamilton Ontario.

The Burning of Black Rock and Buffalo

Whilst on the retreat to Buffalo, remnants of the American militia continued to resist their attackers and aimed to inflict as much damage as they could. On the road, British forces skirmished with a large body of infantry and cavalry whilst under fire from various artillery pieces situated in primitive earthworks. The defenders were eventually captured by the British, and the guns were seized. In his post-battle report, Riall commented on the situation saying "the enemy maintained his position with very considerable obstinacy for some time but such was the spirited and determined advance of our troops, that he was at length compelled to give way."21

Upon reaching Buffalo, which was in the process of evacuation, Riall ordered the entire town to be put to the torch. Important stockpiles of military supplies including foodstuffs and clothing were all destroyed. This would have been particularly devastating for the American war effort in this region as winter months put considerable strain on both armies and their supply chains. Figure 5 is a later 19th-century drawing of the devastating scene that followed the British arrival in Buffalo.22 When examining this image, one can only imagine the shock the innocent citizens of Buffalo felt after seeing their homes reduced to ashes in the dead of winter.

Figure 5: Sketch of the burning of Buffalo, 1876.

After the battle, Riall also ravaged the port for the second time that year and burned four ships. These being the schooners Ariel, Little Belt, and Chippeway, along with the sloop Trippe.23 In the end, only four buildings were left standing. Many civilians were also killed, scalped, and violated by Indigenous warriors.24 After Buffalo, Riall headed back to Black Rock and did the same thing, in the end only one building stood.25 With his objective complete and Black Rock in ruins, Riall and his men did some brief looting and crossed back to the Canadian side. Figure 6 is a contemporary drawing of the aftermath by Buffalo citizen Legrand St. John, who witnessed the battle firsthand. In this bleak sketch, only chimneys remain of what once was a bustling port town.26 When commenting on the state of the frontier one later historian commented "the whole frontier, for many miles, exhibited a scene of ruin and devastation. Here was indeed ample vengeance for the burning of Newark".27

Figure 6: 1814 Sketch of Buffalo after the fires by LeGrand St John.

Casualty reports on both sides are mixed. British losses are estimated to be 31 killed, 72 wounded and 9 missing. American sources claim their own losses to be 50 killed, 52 wounded, and 67 captured.28 Days after the battle Lt. Gen. Sir George Prevost, British Commander-In-Chief for North America, issued a letter to the Americans expressing his regrets stating "the miseries inflicted upon the inhabitants of Newark" had necessitated such appropriate retaliation and that he would only return to such extremes if "the enemy should compel him again to resort to it".29 Overall, the post-battle actions of the Battle of Black Rock were especially cruel when compared to others during the conflict. Its ferocity paired with the fact it was launched during winter (outside of campaigning season) demonstrates how displeased the British were with the American conduct at Newark.

Irregular Tactics on the Niagara Frontier and Beyond

As seen in the Battle of Black Rock, warfare in this theatre was quite daring and unconventional. Though the story of Black Rock is just one case, many operations within the Great Lakes theatre displayed similarities in the tactics deployed and the conduct of the combatants. The fighting was intimate and involved well-planned raids, not large-scale ship-on-ship confrontations commonly associated with the Lake Erie theatre.30 Both sides had objectives to capture or destroy, such as forts, ports, and batteries. By holding these key points and destroying vital enemy provisions, troops could amass safely, and further operations into the enemy's country were able to be launched.

In Niagara, the Americans were noted to be especially aggressive in their attempts to take land as they felt holding key strongholds would force the British into peace negotiations.31 Attacks on important settlements like Black Rock were also quite demoralizing to the enemy psyche. A more famous example of this style of retaliatory raiding can be seen with the American attack on York and the subsequent British retaliation on Washington. These attacks left lasting impressions on both civilians and soldiers and were long remembered for their horror and loss.32 Another common type of raid conducted on this frontier was cutting-out attacks. These daring operations involved raiders commandeering enemy ships and repurposing them for themselves. Both sides saw having a large pool of ships as the key to victory on the lakes as with them the nation could control naval supply routes, fire devastating bombardments on fortified positions, and launch smaller oar-powered landing craft.33 These heavy vessels were always in short supply due to time and resource constraints, therefore stealing was much more efficient and cost-effective. British forces likely chose to burn the ships at Black Rock due to time constraints and harsh winter weather. On a side note, one of the earliest naval operations on the lakes was a cutting-out raid on Fort Erie launched out of Black Rock. Moreover, the two vessels the Americans aimed to seize (Caledonia and Detroit) were originally "cut out" by the British after a successful battle.34

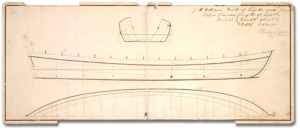

The capture of enemy territory in this theatre was no small feat. Hundreds of batteries lined the rugged riversides at commanding vantage points. Many crossings were made and attempted during the conflict with varying levels of success. An important tool employed by both sides to pull off these daring crossings was small wooden watercraft. The Niagara River created a natural border between the two powers. There was no bridge, so all crossings had to be done by boat. As seen at Black Rock, British forces led by Gordon used these small boats and sought to catch the Americans by surprise and overwhelm them with their landing force. Oar-powered vessels were the backbone of small-unit raids and siege operations.35 Though none were mentioned by name in any report on the battle, British forces likely used batteau watercraft in their landing attempts at Black Rock. First used by French explorers in the mid-1600s, the batteau (meaning "boat" in French) became widespread throughout the frontier as they were cheap to construct and easy to transport overland.36 These boats were designed to be simple transports for men and cargo on inland waterways. Batteau had a flat bottom with no keel, which allowed them to traverse shallow waters and easily beach on shore. The exact specifications vary but most batteau were around 30 feet long, 5 feet wide, and could carry two to three tons of cargo.37 Though none survive today, figure 7 offers a glimpse at these rugged vessels (specifically a Canadian variant) through a contemporary sketch.38

Throughout the War of 1812, batteau vessels were the backbone of the British logistic network and could bring provisions and heavy ordnance (i.e. cannons) to shipbuilding yards, forts, and depots normally inaccessible to other vessels. In the first year of the war, the British alone had

Figure 7: Drawing of a Canadian batteau,1814.

263 batteau deployed across various posts.39 Though there is no mention of batteau being used at Black Rock, batteau were specifically mentioned by name in British reports of the capture of Fort Niagara that took place just days prior.40 Because they were still intact after the battle, it is highly likely that the same boats used at Niagara were transported overland and used in the attack on Black Rock.

Conclusions

Though the Battle of Black Rock isn't as widely known as some other Niagara Region engagements such as Queenston Heights or Lundy's Lane, it stands as a great exemplar of more common day-to-day operations in the Niagara region. By closely examining the battle of Black Rock, the intricacies of irregular amphibious warfare in the Niagara Region are put on full display. From using feared and unconventional Indigenous warriors to devastating barrages, Black Rock was truly a complex operation with its success revolving around the cooperation of various assets working in unison. In the grand scheme of the conflict, the battle had little effect on the course of the war. Conflict continued and many more would fall until peace was finally achieved with the Treaty of Ghent in 1814.

-

Donald Skaggs, The Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812. (Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), ProQuest Ebook Central., 101. https://ebookcentral-proquestcom.proxy.library.brocku.ca/lib/brocku/detail.action?docID=4016086 ↩

-

Figure 1: [Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division,] map, the New York Public Library, "Map of part of Niagara River," New York Public Library Digital Collections (1820). https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-f14e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 ↩

-

Merton Wilner, Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History. (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Pub. Co., 1931), 662. https://archive.org/details/niagarafrontiern02wiln/page/666/mode/2up?q=black+rock ↩

-

Skaggs, The Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812, 106. ↩

-

George Prevost, “A Proclamation,” American and Daily Commercial Advertiser, February 1, 1814. https://mdhistory.msa.maryland.gov/msa_sc3392/msa_sc3392_3_58/pdf/msa_sc3392_3_58-0108.pdf ↩

-

Robert Quimby, The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study (Michigan State University Press, 1997), 356. https://archive.org/details/usarmyinwarof1810000quim/page/360/mode/2up ↩

-

Figure 3: [Sir Phineas Riall,] Painting, Unknown, World History Encyclopedia (1815). ↩

-

Quimby, The U.S Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study, 358. ↩

-

Author Unknown, “Frontier News,” The War, December 28, 1813. https://dr.library.brocku.ca/bitstream/handle/10464/5636/Dec28_1813.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y ↩

-

Phineas Riall, “After Action Report,” The London Gazette, February 26, (1814), 438. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/16862/page/438 ↩

-

Figure 4: [Black Rock in July 1813,] Drawing, Peter A Porter, Buffalo History Museum (1813). ↩

-

Ernest Cruikshank, The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in 1812-4, vol. 9, December 1813 to May 1814 (New York: Arno Press, 1971 [1908]), 74. https://archive.org/details/documentaryhisto09lund_1/page/70/mode/2up?q=400&view=theater ↩

-

Cruikshank, The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in 1812-4, 70. ↩

-

Author Unknown, “Frontier News,” The War, January 4, 1814. https://dr.library.brocku.ca/handle/10464/5734 ↩

-

Cruikshank, The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in 1812-4, 8. ↩

-

Wilner, Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History, 673. ↩

-

Wilner, Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History, 674. ↩

-

Riall, “After Action Report.” ↩

-

Figure 4: [24 Pounder Gun, Circa 1812], Photograph, James Yolkowski, War of 1812 Bicentennial (2012). https://www.warof1812-bicentennial.info/imagedesc/24_pounder_gun_circa_1812.php ↩

-

Wilner, Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History, 675. ↩

-

Riall, “After Action Report,” 438. ↩

-

Figure 5: [Buffalo, N.Y. Burned by the British, Dec 30th, 1813, 1876,] Drawing, C.B. Taylor, The Centennial History of the United States of America, Boston: Lee and Shepard, (1876). https://archive.org/details/centennialhistor00tayl/page/306/mode/2up?view=theater&q=black+rock ↩

-

Author Unknown, “Niagara Frontier,” The War, January 25, 1814. https://dr.library.brocku.ca/handle/10464/5735 ↩

-

Cruikshank, The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in 1812-4, 79-80. ↩

-

Quimby, The U.S Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study, 360. ↩

-

Figure 6: [Views of Main Street with Chimneys,] drawing, Legrand St. John, Buffalo History Museum (1861). https://buffalohistory.smugmug.com/Public-Collections/LeGrand-St-John-Drawings ↩

-

C.B. Taylor, Buffalo, Centennial History of the United States of America, Boston: Lee and Shepard (1880). https://archive.org/details/centennialhistor00tayl/page/306/mode/2up?view=theater&q=black+rock ↩

-

Cruikshank, Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History, 73-74. ↩

-

Prevost, “A Proclamation.” ↩

-

Skaggs, The Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812, 109. ↩

-

Benjamin Armstrong, “Raiding on the Lakes 1812-1814,” in Small Boats and Daring Men: Maritime Raiding, Irregular Warfare, and the Early American Navy (University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 74. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2582/battle-of-york/ ↩

-

Harrison W. Mark, “Battle of York,” World History Encyclopedia (2024). https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2582/battle-of-york/ ↩

-

Skaggs, The Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812, 105. ↩

-

Armstrong, Raiding on The Lakes, 90. ↩

-

Armstrong, Raiding on the Lakes, 73. ↩

-

Robert Malcomson, “Nothing More Uncomfortable than our Flat-Bottomed Boats: Batteaux in the British Service during the War of 1812,” The Northern Mariner / Le Marin du Nord (2003), 17. ↩

-

Malcomson, “Nothing More Uncomfortable than our Flat-Bottomed Boats,” 19. ↩

-

Figure 7: [Drawing of a Bateau, 1814,] drawing, Archives of Ontario (1814). https://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/1812/big/big_050_boat_plan.aspx ↩

-

Malcomson, Nothing More Uncomfortable than Our Flat-Bottomed Boats: Batteaux in the British Service during the War of 1812, 21. ↩

-

Cruikshank, Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History, 18. ↩