From Grain Terminals to Waterfront Condos:

An Examination of Buffalo and its Changing Industrial Landscape through the 19th and 20th Century

Mathew Wuhlar

Buffalo - 2025

Prior to the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, the Nineteenth and early Twentieth century saw the Port of Buffalo as a key force within trade on the Great Lakes that transported and stored tens of millions of bushels of grain and other materials. Many families of the wave of Buffalo settlers in the 1830s logged wood, primarily growing grain. By the start of the 1910s, former Professor M. Melina Svec writes, "Buffalo was a powerhouse of grain and raw element exportation."1 However, the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 brought decline in this volume, making Buffalo turn to other avenues of city development to keep income flowing in, such as real estate, journalism, and education. While Buffalo's port was declining, the twentieth century port was transformed by the steel industry. This paper will briefly outline the Port of Buffalo before, during, and after the twentieth century and note aspects of industry in Buffalo within these periods, analyzing articles and statistics from the St. Lawrence Seaway, Buffalo, and professionals elsewhere to compare the two routes and how the Seaway was much more desirable to companies than the Erie Canal. This paper will also uncover how the Port of Buffalo has been struck with change for many decades, and how the city initially succeeded in adapting to these changes, but overtime was unable to keep up with them.

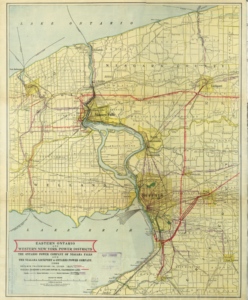

Figure 1: Map of Eastern Niagara (Ontario) and part of Western New York State, 1906.

Buffalo's port must be examined prior to the Seaway to provide context for its flourishing in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The city of Buffalo's geographical position as furthest east on Lake Erie made it the most direct route to the Erie Canal, a hotspot for ships to be, as routes bound west to east on the Great Lakes would end in Buffalo before heading for the Atlantic Ocean. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical condition of Buffalo in relation to the Niagara River and Erie Canal.2 It also shows shipping routes depicted as a black line (in the water), townships highlighted yellow and canals coloured red. Brian Hayden, a reporter for the Buffalo News, articulates Buffalo of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as the hub for all Great Lakes trading headed east.3 Canadian ships needing access to the Atlantic were forced to pass through Buffalo, the Erie Canal being the only canal in the region as of 1819, ten years before the original Welland Canal was complete. Not only is its geographical condition an influential factor in the success of Buffalo's port at this time, but the ability to industrialize at a rate matching the ever-increasing cargo shipments echoed that dominance. Professor and author of Port of Buffalo Henry H. Baxter, writes that Buffalo was moving nearly two million bushels of grain in 1841 to over fifty-eight million by 1942 and with the introduction of hydroelectric energy powered grain elevators in 1842, this allowed grain to be stored and not just passed through the port.4 Machines moving large quantities of materials increased efficiency and worker safety as the port did not require workers to handle large quantities of grain, instead needing to scoop grain into these elevators.5 Figure 2 illustrates the absence of workers from the docks, as they are likely inside the elevators sorting and storing grain.6 Baxter further reveals that during winters many boats docked in the harbour with grain still on board, extending port worker jobs later into the season, monitoring vessels to ensure no breakage of the boats or robbery occurred.7 The introduction of grain elevators contributed to a slightly safer work environment and opened new jobs, such as steel manufacturing, as Buffalo State College economics professor Curtis Haynes suggests.8 Moreover, the port's automation and concern for workers displayed in the nineteenth and early twentieth century demonstrates an ability to anticipate changes within the maritime industry and promote worker's longevity through less physically demanding jobs. As a result, this incentivizes its current workers to stay at the port while drawing potential laborers to the port with its modern appeal.

Figure 2: The Canal Harbor, Buffalo, N.Y., circa 1910-1920.

Baxter further indicates that at the turn of the twentieth century raw ores and other rock frequented ship cargoes, while the hydropower industry from Niagara Falls stimulated immigration to Buffalo, initiating cement manufacturing jobs to build structures where they would generate, receive, and maintain hydroelectric power.9 Canada and the U.S, benefiting from trends of immigration and the migratory nature of hydropower, strengthened their maritime relationship with production and exportation, driving Buffalo's maritime activity growth. Exacerbated by the Erie Canal being the exclusive access point to the Atlantic, they began concentrating on this production in the Niagara region. Several canals were built during the 19th century but as the 20th century progressed, many canals were rebuilt to accommodate the growing size of ships, to accommodate increased cargoes.10 Thus, the project of constructing the St. Lawrence Seaway came into fruition.

While constructing the Seaway, American workers and government officials expressed mixed feelings about the project. Marsh emphasizes that Canadian Seaway representatives sought to include the U.S. in building the Seaway in the early 1930s because of the need for more workers. However, American professionals from railroad companies, other port directors, and lobbyists saw no value for the United States in its construction.11 The Seaway would directly compete with the Erie Canal and divert economic prosperity away from the port. American maritime representatives rejected a 1932 plan to construct the Seaway following these concerns.12

However, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent succeeded in convincing United States President Harry S. Truman to support the Seaway project by threatening for Canada to independently construct it. This would cut the USA out of any profit potential which had previously been experienced with the exchange of hydropower, as crossing the United States border was no longer needed to have a busting waterway connected to the Atlantic.13 Americans built much of the Seaway, and the route was finished in five years.14 In addition, Buffalo newspapers recorded workers as being in favour of the endeavor. One such account comes from a column published on April 11, 1955, in "Pole to Pole" by the Polish Everybodies Daily, where the writer asserts morale is high amongst workers as they hoped to gain notoriety by working at the Port of Buffalo, thus being associated with the Seaway.15 A sense of pride from both workers and government is a key feature of the mid 1950s, which quickly changed after the Seaway's completion in 1959 during its first shipping season.

In the Seaway's first open season, America's economic benefit was not as promising as previously thought during construction. Journalist Marc Heller states that nearly 7,500 ships utilized the new waterway, tracing the original St. Lawrence River.16 This marked the start of Buffalo's decline as the path of the Seaway negated the Port of Buffalo entirely with its entry way further west on Lake Erie, and not traversing its entirety from west to east. The architecture of the Seaway had many commercial consequences on Buffalo too, with Hayden relaying a decrease of nearly fifty-eight million bushels of grain passing through the Port of Buffalo. The port's train connections were also impacted because the Seaway reached the Atlantic by directing ships north, not east as the Erie does, causing stagnation on eastbound tracks.17 Hayden further relays a statement from Nancy Alcalde, the St. Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation's spokeswoman, where she reminds listeners that the Seaway's route offers shipping cost reductions.18 Marc Heller confirms these claims, explaining $1.2 billion dollars were saved by Canadian and American shipping companies in 2000 by utilizing the Seaway instead of Buffalo's path to the Erie canal.19 Moreover, the direct path of the Seaway (and the minimization of stops and workers) lowered costs, making the waterway more appealing to companies, with the Seaway offering shorter travel periods to the Atlantic than the Erie Canal.

This dramatic drop in shipping activity in Buffalo affected the economy of the grain industry, but also its workers. Hayden recounts an interview with Bob Grande, a grain elevator worker who scooped grain into the storage units. Grande explains that work had been on a steady decline from the 1960s to the 1990s and found himself doing more work on houses as the 2000s approached.20 The presence of real estate opportunity and improvement became an area of redevelopment focus during this time, with Baxter ensuring much of Buffalo's port waterfront was to become housing.21 Thus, workers were conscious of the damage caused by the Seaway to their city's port, adapting their skillset to stay employed. Additionally, Heller summarizes a key point in Buffalo's stagnation of shipping: the Seaway was built to accommodate more than the largest ships of the 1950s, and experienced growth in the amount of cargo carried through its route for the first two decades of its operation.22 Conversely, Buffalo was not able to widen port infrastructure (suggested by the Seaway's seizure of potential traffic), limiting the capacity of ships that could pass through as watercraft dimension standards had changed, permitting only older ships to access the port. Thus, the desire to ship via the Seaway for companies (and likely ship captains) grew.

Other methods of Buffalo's redevelopment included tourism, education, and journalism. Heller articulates that Buffalo had seen an increase in cruise ship tourism23 alongside the development of waterfront estate as Baxter writes. Heller provides a small rationale for why waterfront estate seems to be trending, pointing out that similar projects are occurring in Canadian ports like Oswego.24 The relationship explored earlier, reliant on hydro production between Canada and the United States, continues even as Buffalo's maritime activity declines. Buffalo continues seeing the growth of Canadian ports, despite this inspiration being opposite hundred years prior, as Canada would have looked to Buffalo for ideas to stimulate its growth and infrastructure. In the 1970s, the grain elevators and their idle presence drew the attention of scholars. The 1979 edition of the UB Reporter published on June 7, details University at Buffalo Professor Reyner Banham's plans for a conference discussing the grain elevators and how they symbolize Buffalo's once dominant history through architectural design.25 Banham notes that the materials used and specific company ownership such as Cargill Grain company of the grain elevators, reveal who controlled much of the port, while the materials used to construct the elevators uncover industry within Buffalo such as concrete pouring.26 Grain elevators have continued to stand absent and empty, as the author of Abandoned article "The Plight of Buffalo's Elevators" writes. Elevators such as the "Electric Elevator" and "Cargill Superior Elevator" built between the 1910s-1920s, have stood empty since the completion of the Seaway.27 But, even in the early wake of the Seaway's effect on Buffalo's port, elevators were being converted into electric energy sources to maintain some of their economic capital, demonstrating Buffalo's persistence on adapting to new landscapes, demands, and technologies of industries.

In the last twenty years, the Port of Buffalo has not regained the level of commerce it once had, but new legislature and non-marine industry pose a partial comeback for the city. Heller reports as of 2005 that the Port has less shipping volume than Oswego, but is utilizing energy sources such as petroleum coke, exporting it through the rail system established decades prior.28 In addition, Hayden notes that sustainable energy legislation may cause taxes to be raised within automotive shipping.29 Increased rates may make the cost of shipping on the Great Lakes feasible again, allowing ports in the region to experience some resurgence of revenue.30 Hayden's article was published in 2009, prior to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the current date this paper is submitted, there is no data regarding how the Port of Buffalo has battled the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Canadian Press Reporter Christopher Reynolds' article "Cargo ticks up along St. Lawrence Seaway, despite grain decreases," provides figures for how the Seaway has battled restrictions and shutdowns during the pandemic. Reynolds relays that transportation of grain fell, but raw and processed materials as well as agriculture experienced growth in shipping on the Seaway31 Perhaps this is due to demand for grain storage, as explored in Heller's article, as the need to transport grain has halted in the aftermath of the pandemic as grain is less perishable than other produce or immediate as materials like metal or chemicals. Furthermore, because the Seaway has experienced a return of volume in cargo and statistics on Buffalo are absent, it is likely that Buffalo has not seen much growth as shipping companies seem to choose the Seaway over the Erie Canal. Reynolds further articulates a decrease in grain exportation of 20 per cent in the Great Lakes region in 2020.32 While the Seaway was able to draw in some activity during the pandemic, Heller's article points out that although the Seaway was built to accommodate the largest ships of the 1950s, the current standard size of many cargo ships has nearly outgrown the Seaway's parameters.33 Moreover, because the city of Buffalo has not renovated their port, the city is likely suffering similar circumstances to the Seaway's route, experiencing less activity due to the size of the port and narrow entrances to the Erie Canal.

In conclusion, during the nineteenth century Buffalo's position in the Great Lakes region as the most eastern access to the Atlantic led to frequent passage through the Port, resulting from unique infrastructure like the Erie Canal. The Erie Canal provided a route to the Atlantic from the Great Lakes region, while making Buffalo a key shipment port. When faced with industrialization, the port capitalized on other infrastructure such as grain elevators and the growing steel industry. Grain elevators stored massive quantities of grain requiring workers to monitor these and new machines coming to the port, and substitute port labour jobs such as stevedores with steel mill jobs, which would have intersected through the implementation of Buffalo's railway system. However, in 1959 the St. Lawrence Seaway was completed, offering ships an alternative route to the Atlantic through Montreal which was cheaper and easier to navigate than a route leading to the Erie Canal, as the Seaway was one direct route rather than separate ports lining the path. This caused the Port of Buffalo to suffer devastating inactivity, with millions of grain bushels ceasing to come through the port after 1959. This also impacted on workers who experienced layoffs. The city of Buffalo implemented waterfront residential buildings, held conferences supported by the University at Buffalo, and allowed companies to own grain elevators to secure funds. These efforts fell short however, resulting in further decline. What the future holds for Buffalo is unknown, however, like many Great Lakes cities that have been force to adapt, the Port of Buffalo may find its way through the renewal and restructuring of its waterfront landscape.

-

Melvina Svec, "The Port of Buffalo: Where the Water Routes and Trucking Routes of the Automobile Carriers Meet," The Journal of Geography 38, no.5 (May 1938), 173. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Eastern Ontario and Western New York Power Districts], map, Ontario Power Company (1906). ↩

-

Brian Hayden, "St. Lawrence Seaway at 50: A Bypass for Buffalo's Port: Seaway Allowed Ships to Avoid a Stop in Buffalo," Tribune Business News, (Jun. 21, 2009), Para 6. ↩

-

Henry H. Baxter, "Port of Buffalo," Encyclopedia of New York State, Syracuse University Press (2005), Para. 4. ↩

-

Baxter, "Port of Buffalo." ↩

-

Figure 2: [The Canal Harbor, Buffalo, N.Y., circa 1910-1920], photograph, Library of Congress. ↩

-

Jeff Z. Klein, "Buffalo's Vanished Maritime Past," Belt Magazine (2020), Para. 5. ↩

-

Curtis Haynes Jr., "Buffalo's story: African Americans deal with decline in the former city of steel," Dollars and Sense (1995), Para. 1. ↩

-

Haynes, "Buffalo's Story." ↩

-

Marsh, "The Construction." ↩

-

Marsh, "The Construction." ↩

-

Marsh, "The Construction." ↩

-

Marsh, "The Construction." ↩

-

Marsh, "The Construction." ↩

-

Author Unknown, "From Pole to Pole," Polish Everybody's Daily, Apr. 11, 1955. ↩

-

Marc Heller, Northern New York's seaway's place in world shipping shrinks every year (Washington: Tribune Content Agency LLC, 2005). ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawrence Seaway at 50." ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawrence Seaway at 50." ↩

-

Heller, "Northern New York's Seaway." ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawrence Seaway at 50." ↩

-

Baxter, "Port of Buffalo." ↩

-

Heller, "Northern New York's Seaway." ↩

-

Heller, "Northern New York's Seaway." ↩

-

Heller, "Northern New York's Seaway." ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Grain elevators nationally important," UB Reporter, Jun. 7, 1979. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Grain elevators." ↩

-

Author Unknown, The Plight of Buffalo's Elevators, Abandoned, Mar. 16, 2017. ↩

-

Heller, "Northern New York's Seaway." ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawrence Seaway at 50." ↩

-

Hayden, St Lawrence Seaway at 50." ↩

-

Christopher Reynolds, Cargo ticks up along St. Lawrence Seaway, despite grain decreases (Toronto: Canadian Press Enterprises Inc, 2022). ↩

-

Reynolds, "Cargo ticks up." ↩

-

Heller, "Northern New York's Seaway." ↩