The Erie and the Welland:

Competing 19th-Century Canals

Mark Frampton

Buffalo - 2025

The Erie Canal opened in 1825 and was the first all-American waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Great Lakes basin. With this new waterway in place, the St. Lawrence River would no longer be the preferred route for transporting valuable natural resources from the fertile lands of western North America to the Atlantic Ocean and then on to Europe. The growing population centres in the interior of New York State could now have agricultural goods shipped to them directly and in turn. would have improved access for their manufactured goods to the midwestern territories of Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois.

Upper Canada's response to the Erie Canal was to build a canal of its own to allow navigation across the Niagara peninsula and join Lakes Erie and Ontario. William H. Merritt was a St. Catharines businessman, future Member of Parliament, and the visionary behind the Welland Canal. Merritt owned various mills along the Twelve Mile Creek, which often ran low on water during the summer months. The inconsistent flow along Twelve Mile Creek inhibited his mills from functioning; a canal across Niagara would alleviate his low water concerns. As early as 1818, Merritt had envisioned a Canadian canal spanning the Niagara peninsula to join the Great Lakes.1 But by the time the Erie Canal had opened for business in 1825, the Welland Canal had yet to be started.2 The Welland Canal Company was officially incorporated by the Province of Upper Canada in 1824 and the first shovelful of sod was finally turned later that year.3 The competition for shipping superiority in the Great Lakes region had begun. This essay will examine the competitive relationship between the Erie and Welland canals from 1829 to the 1880s.

The Erie Canal

The Erie Canal opened to shipping traffic in 1825. The inaugural passage through the new canal was made by Governor DeWitt Clinton and selected dignitaries aboard the Seneca Chief, on October 26, 1825.4 Now, nearly 200 years since that first trip through the Erie Canal, a replica of the Seneca Chief is on display at the Buffalo Maritime Centre shown in Figure 1, to commemorate this anniversary.5

Figure 1: Replica of the Seneca Chief.

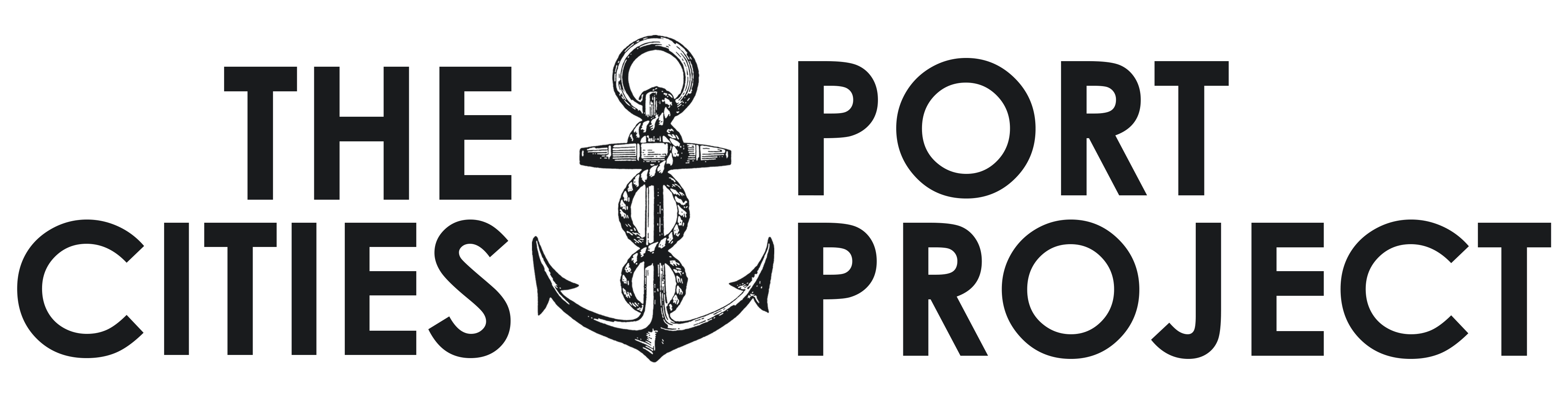

The construction of the Erie Canal was no small feat of engineering. In the early 19th-century there were few American engineers skilled in canal building and had to overcome the obstacles of distance and elevation.6 The completed Erie Canal spanned 363 miles and required 82 wooden locks to overcome the nearly 600-foot rise in elevation from the Hudson River valley to Buffalo, New York.7 Figure 2 shows the path of the Erie Canal and includes the dates that construction was completed for each section.8 The Erie Canal's route would rely on a combination of engineered and natural waterways. Beginning in Rome, New York, the canal would be built towards the east and west termini simultaneously.9

Figure 2: The route of the Erie Canal.

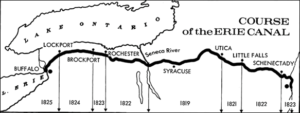

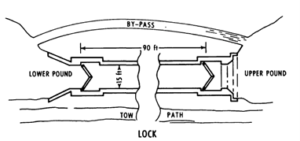

The original Erie Canal was 40-feet wide and 4-feet deep, just large enough to allow low-

draught barges to navigate the waterway. Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the dimensions

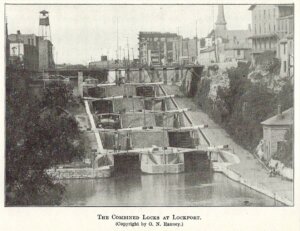

of the Erie Canal and a representative lock.10 The locks of the canal were 90-feet long and 15-feet wide and accommodated boats measuring 61-feet in length, 7-feet in width, and with 4-feet of draft.11 Despite the size limitations of the Erie Canal, it would be instrumental in transforming New York City into the major seaport on the east coast of the United States. The Erie Canal would reduce both shipping costs and transit times, stimulate economic growth in New York and the western territories, and be the catalyst for the rapid population growth in many small towns along its route; not the least of which was the Port of Buffalo. This can be seen in New York's population increase, which rose over 280% from 1825 to 1835!12 The growth and development of towns like Buffalo, Utica, Albany, Rochester, and Syracuse resulted in the canal acquiring the moniker "Mother of Cities."13 This moniker was especially true for the town of Lockport, which was home to the only twinned locks constructed for the canal. Figure 4 shows an early photograph of the combined flight locks at Lockport passing through the centre of town and were the only locks along the original canal that were constructed in pairs. 14

Figure 3: A schematic diagram of the Erie Canal (top) and from a typical lock (bottom).

Figure 4: Combined locks at Lockport, New York, 1906.

The Welland Canal

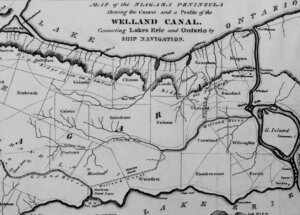

The First Welland Canal was built from Port Dalhousie on Lake Ontario to Port Maitland, and later Port Colborne, on Lake Erie in 1833. Figure 5 depicts the first canal route through the Niagara Peninsula.15 Originally a self-serving project of its visionary and founder William Hamilton Merritt who desired a reliable water supply for his mills, the Welland Canal made use of natural waterways such as Twelve Mile Creek, Dick's Creek, Broad Creek, and the Welland River, to cross the Niagara peninsula.16 The original plans for the Welland Canal featured a two-mile subterranean tunnel to be dug between Port Robinson and Allanburg, but these plans were changed and a deep channel was cut through the high elevation landscape.17 The canal engineers, many of whom had worked on the Erie Canal, had to manage the difficult terrain of the Niagara Escarpment while navigating multiple setbacks such as collapsing canal banks to get the canal operational.18

Figure 5: George Keefer's map of the First Welland Canal through the Niagara peninsula.

The Welland Canal was built with 40 wooden locks to overcome the 100 metre rise of the Niagara escarpment.19 Originally, the lock dimensions of the Welland Canal were to mirror those of the Erie Canal, however, American associates and investors of the Welland Canal Company insisted that the canal be built with larger dimensions to facilitate sloop navigation.20 Lock dimensions were finalized at 110-feet long by 22-feet wide with a depth of 8-feet to accommodate larger vessels that could carry a burden of 90-120 tons.21 More importantly, the Welland Canal did not require canal-bound vessels to unload at either end of the canal.22 The first ships through the canal, the Ann and Jane and R.H. Broughton, sailed from Port Dalhousie to the Niagara River via the Welland River in November of 1829.23

The prospect of a canal circumventing Niagara Falls was enticing to American investors, particularly those that were in favour of the proposed, but ultimately unchosen, Ontario route for the Erie Canal. The Welland Canal connected western producers on the upper Great Lakes with a growing consumer base on Lake Ontario. This enhanced trade was beneficial to both Upper Canada and New York State alike. Many residents of Buffalo owned stock in the Welland Canal Company and supported the Welland Canal as an alternative to the Erie Canal.24 The option for shipping goods through a cheaper route promoted competition between the Welland and Erie canals. Some in New York State thought that the Welland Canal would never truly affect the Erie Canal. Soon after the Welland Canal opened, Erie Canal toll revenues saw a decrease; it would seem that the Welland Canal was now a cause for concern.25

Competition between the Erie and the Welland

The cheaper cost of shipping and the amount of cargo transported through the Welland Canal weighed on the New York Canal Commission. By 1832, legislation was passed to begin improvements on the Erie Canal. After nearly a decade in service, the Erie Canal was showing its age. The locks and canal banks were in increasingly poor condition and required constant upgrades. By January of 1834, the decision had been made to improve the locks, widen the canal, and construct aqueducts.26 By the time improvements to the Erie Canal were completed in 1862, the canal would see its dimensions enlarged to 70-feet wide and 7-feet deep, and its locks enlarged to 110-feet by 18-feet.27 These enlargements would increase the capacity of the canal by nearly eighty percent.28 Throughout the course of improvements the canal would be straightened and in the end, would be shorter than the original canal by 13 miles.29

Improvements to the Erie Canal could not come soon enough for everyone, however. A report from the Select Committee on the petition of inhabitants of the county of Oswego to the legislature of the State of New York lamented that, "[t]he lethargy with which the Canadian people slumbered for the last century, has been thrown off, and they are now fully awake to the importance of internal improvements."30 It was becoming increasingly worrisome to legislators that the Welland Canal was diverting shipping traffic from the Erie Canal.31

The First and Second Welland Canals have been characterized as feeder canals for the Oswego Canal.32 The shorter distance through the Welland Canal allowed vessels to reach Oswego in less time and avoid approximately 155 miles of New York canals. More importantly, these ships avoided paying Erie Canal tolls.33 Once vessels reached Oswego they could sail through the Oswego Canal and reach New York City in less total travel time. By 1845, it was estimated that the loss of revenue from shipping traffic choosing the Welland and Oswego Canals was costing citizens of New York State nearly $100,000 in annual revenue; this estimate was predicted to continually increase once the Second Welland Canal, which would be able to accommodate ships of larger size, was completed.34

Most shipping traffic that sailed through the Welland Canal was of American origin. In 1845, nearly all American owned vessels that locked through the Second Welland Canal were destined for American ports along Lake Ontario.35 For example, during the 1854 shipping season there were 1162 downbound passages through the Welland Canal by American-owned vessels, and of those ships, 1027 (88%) were destined for the ports of Oswego, Ogdensburg, Port Vincent, and Clayton, New York, while only 118 (10%) American vessels were destined for Canadian cities.36 Furthermore, there were several Buffalo-based vessels that availed themselves of the shorter and cheaper Welland Canal to move between lakes Erie and Ontario despite the western terminus of the Erie Canal being much closer to home.

Data from the 1875 Welland Canal shipping season paints a similar story. American-owned vessels made 646 downbound trips through the Welland Canal with 529 (82%) ships destined for New York ports.37 Despite all attempts to encourage shipping through the Erie canal, American entrepreneurs were not so loyal and frequently chose the cheaper and shorter Welland Canal to move goods between the lakes.

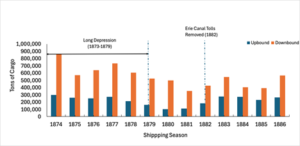

The decrease in shipped tonnage and the loss of tolls paid on the Erie, coupled with the Long Depression of the 1870s, ultimately resulted in the elimination of tolls to shipping traffic on the Erie Canal in 1882.38 This new favourable economic environment for American shippers was beneficial as American-owned vessels increased their use of the Erie Canal. An analysis of shipping data shown in Figure 6 for 1874 to 1886, suggests a decreasing reliance of American shipping companies on the Second and Third Welland Canals.39 The Erie Canal was returning to its position of prominence among American shipping fleets. The revitalization of the Erie Canal was short lived as shipping tonnage would peak in 1880 and then continually decline.40 American shipping traffic through the Welland Canal would begin

Figure 6: American shipping traffic through the Welland Canal for the years 1874 to 1886.

to return slowly to the Canadian route once the Third Welland Canal opened in 1881.

Improvements to the Erie Canal throughout the 19th century did not go unnoticed in the Niagara region. The Board of Trade for the city of St. Catharines encouraged the Canal Commission to deepen the Welland Canal to 14-feet to offset the improvements that had been made to the Erie Canal.41 The Board of Trade anticipated that a failure to deepen the Welland Canal would adversely affect Canadian business interests. In their view, the Welland Canal should "seek the control, as much as possible, of the Western traffic, and take it to tide water."42 They had envisioned the Welland Canal diverting shipping traffic from the Erie and other New York State canals. An improved Erie Canal was now becoming a concern to the Niagara shipbuilding industry as well as to other canal associated industries.

The Erie Canal saw an additional series of improvements toward the end of the 19th century to increase and modernize its locks. The Barge Canal Act incorporated the Erie, Oswego, Cayuga, and Seneca Canals into the Barge Canal System. When the new canal opened in 1909, the minimum depth was 12-feet, and it had only thirty-five locks.43 The beginning of the 20th century saw the Erie Canal's role as a shipping pipeline become greatly diminished and it is now primarily used as a recreational canal.

Conclusion

The Erie Canal opened up the North American interior and connected the Great Lakes to the Atlantic seaboard. The increase in the flow of goods between the midwestern territories and New York State would improve the economic situation for many. The arrival of the Welland Canal a few years would bring about a competition for shipping traffic. In the mid-nineteenth century, a twenty-year improvement project on the Erie Canal was undertaken to regain its superiority over its Canadian neighbour. During the competition for shipping traffic both canals experienced various highs and lows with each carrying out new rounds of improvements to better the other canal. The Welland Canal would edge out the Erie for dominance and secure much of the American shipping traffic in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

The success of the Erie and the Welland Canals diverged with the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the twentieth century. The Erie Canal assumed a role predominantly as a recreational waterway, where it would contribute largely to the tourism industry of New York State. The fourth iteration of the Welland Canal would strengthen and further the legacy of the canal as an important link within the St. Lawrence Seaway.

-

Roberta M. Styran, and Robert R. Taylor, This Great National Object: Building the Nineteenth-Century Welland Canals, (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2012), 4. ↩

-

Styran and Taylor, "This Great National Object," 8. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Welland Canal, An Act to Incorporate Certain Persons Therein Mentioned, Under the Style and Title of the Welland Canal Company," (York: John Carey, 1825). ↩

-

Janet Dorothy Larkin, Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (State University of New York Press, 2018), 72. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Replica of the Seneca Chief], photograph, Buffalo Maritime Center, n.d. ↩

-

Larkin, "Overcoming Niagara," 91. ↩

-

Ronald E. Shaw, Erie Water West (University of Kentucky Press, 1990), 84. ↩

-

Figure 2: [The route of the Erie Canal], map, Janet Dorothy Larkin, "Overcoming Niagara," 84. ↩

-

Larkin, "Overcoming Niagara," 69. ↩

-

Figure 3: [A schematic diagram of the Erie Canal (top) and from a typical lock (bottom)], diagram, Walter B. Langbein, "Hydrology and Environmental Aspects of Erie Canal (1877-99)," (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), 24. ↩

-

Wilfred H. Schoff, "The New York State Barge Canal," Bulletin of the American Geographical Society 47, no.5 (1915), 326. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Census of the State of New-York, for 1855; Taken in Pursuance of Article Third of the Constitution of the State and of Chapter Sixty-four of the Laws of 1855 (Albany, N.Y.: Printed by Charles Van Benthuysen, 1857). ↩

-

Blake McKelvey. "The Erie Canal: Mother of Cities," The New York Historical Society Quarterly 35, no.1 (1951), 55. ↩

-

Figure 4: [Combined Locks at Lockport, 1906], photograph, O.N Ranney (n.d.) ↩

-

Figure 5: [George Keefer's map of the First Welland Canal through the Niagara peninsula], map, George Keefer and A. Doolittle, Brock University Digital Archives (1828). ↩

-

Styran and Taylor, "This Great National Object," 54. ↩

-

Styran and Taylor, "This Great National Object," 122. ↩

-

Styran and Taylor, "This Great National Object," 22. ↩

-

Styran and Taylor, "This Great National Object," xiii. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Third Report from the Select Committee Appointed to Examine and Enquire into the Management of the Welland Canal (Toronto: William Lyon Mackenzie, 1836), 235. ↩

-

Larkin, "Overcoming Niagara," 93. ↩

-

Janet D. Larkin, "The Canal Era: A Study of the Original Erie and Welland Canals within the Niagara Borderland," American Review of Canadian Studies 24, no.3 (1994), 300. ↩

-

Larkin, "Overcoming Niagara," 102. ↩

-

Larkin, "Overcoming Niagara," 85. ↩

-

Author Unknown, A memorial to the legislature of the state of New York, upon the effects of the passage of the trade of the western states, through the Welland and Oswego canals, upon the income of the state and the interests of its citizens," (Rochester: Press of E. Shepard, 1845), 9. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Documents of the Assembly of the State of New-York, Fifty-Seventh Session (Albany: E. Croswell, printer to the state, 1834), ↩

-

Author Unknown, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, United States Department of the Interior, n.d. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Sixty-First Session (Albany: B. Croswell, printer to the state, 1838), 2. ↩

-

Langbein, "Hydrology and Environmental Aspects," 24. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Documents of the Assembly of the State of New-York, Fifty-Seventh Session (Albany: E. Croswell, printer to the state, 1834), 3-4. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Documents of the Assembly of the State of New-York, Fifty-Eighth Session (Albany: E. Croswell, printer to the state, 1835), 4. ↩

-

John N. Jackson, "The Construction and Operation of the First, Second, and Third Welland Canals," Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 18, no.1 (1991), 475. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "A memorial to the legislature," 3. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "A memorial to the legislature," 3-4. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "A memorial to the legislature," 11. ↩

-

Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1854-1858, RG 43 Vol. 2406). Funding towards the transcription of the Second Welland Canal Registers was provided to Dr. Kimberly Monk from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Research Grant # 430-2018-1113 Visualizing Past Landscapes: Toward Reengaging the Local Historic Environment (2018-2023). Students in Brock University's History 3M61: Local Historical Archeology, undertook the initial draft transcription work during 2020-2021 under the direction of Dr. Kimberly Monk. ↩

-

Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1875-1877, RG 43 Vol. 2406). ↩

-

Author Unknown, The Mighty Chain: A Guide to Canal Records in the New York State Archives, New York State Archives (1992), 7. ↩

-

Figure 6: [American shipping traffic through the Welland Canal for the years 1874 to 1886], chart, "Canal Statistics," (Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Transportation Division, 1874-1886). ↩

-

Author Unknown, "National Register," 7. ↩

-

Board of Trade of the City of St Catharines, Committee on Transportation, Paper on the subject of the enlargement of the Welland Canal (St. Catharines, Ont: Sylvester Neelon, 1875), 6. ↩

-

Board of Trade of the City of St. Catharines, "Paper on the subject of enlargement," 6. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet," 2. ↩