"The Road from Hand to Mouth":

Joseph Dart, and the First Steam-Powered Grain Elevator in America

Lydia Burke

Buffalo - 2025

The Great Buffalo Grain Elevators

In an 1865 speech discussing the history of grain processing, inventor of the grain elevator Joseph Dart said this about his creation: "when the hands of producers and the mouths of consumers are distant by the space of half a continent and even half a globe, the road from hand to mouth is a long one, and oftentimes 'a hard road to travel.' Whatever smooths the roughness of that road cheapens food, and benefits mankind."12 Over a century and a half later, his words still ring true - when it was established in 1843, on the growing port of Buffalo following the creation of the Erie Canal34, Dart's invention of the grain elevator dramatically changed the industrial landscape. It transformed the expanding city of Buffalo and its relationship with Lake Erie, the grain trade across the entire Great Lakes region, and the United States' outlook on colonial expansion and economic production. His dedication to the importance of food security in the developing U.S. led to the creation of machines that still stand as monoliths of post-colonial urbanization and national American identity today. In his own words, Dart carved out the 'road from hand to mouth' for many Americans today by solidifying a lifeline to accessible staple foods for the country. This paper will trace the steel-framed silhouette of Dart's legacy throughout the long lifetime of the grain elevators, analyzing their importance to the development of the Port of Buffalo, their impact to the U.S. agricultural industry, and cultivated consumption during the peak of American industrialization.

American Grain, Buffalo, and the Erie Canal

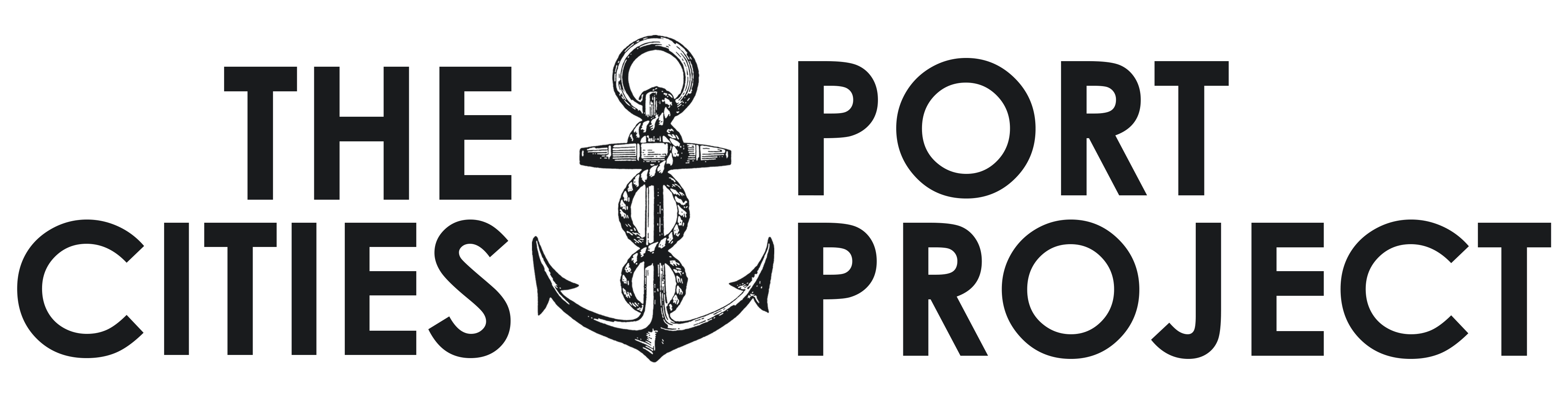

Understanding the creation of the Dart elevators must first start with acknowledging the major innovations that took place within the region which would transform Buffalo into a paramount port for grain handling. Namely, the creation of the Erie Canal would mark one of the most significant shifts for the region's development, as well as the foundation of the use of water transportation for U.S. grain on the Great Lakes. Opening in 1825, the Canal carved out a revolutionary industrial transport route between the Great Lakes and the American hub of commerce, New York City. This established the small village of Buffalo as a meeting point between the farms of Niagara and the expanding western frontiers of farmland growing U.S. wheat, and the international ports of New York.5 Water transportation along the Great Lakes revolutionized the efficiency, speed, and production costs for grain on American soil, with the Erie Canal stated by historian Francis R. Kowsky, to cut "what had been a 3,000 mile journey was now reduced to about 500 miles" for grain exports moving across the U.S now that it no longer required roads or foot travel.6 Furthermore, Buffalo was launched almost immediately into commercial success. The port held a strategic position on the route of the Canal as shown in figure 1, that was deeply important to the movement of people and goods.7 Subsequently, both the harbour and city of Buffalo would undergo a period of rapid settlement and industrialization to keep up with the influx of development that grain had brought into the region.

Figure 1: Map of the Erie Canal route, 1896

The need for the grain elevators can already be seen by the busy conditions of the supply and demand of grain along the shores of early 1800s Buffalo, as Dart himself highlights in his aforementioned speech the connection between the role of grain production and the population growth in the Great Lakes region.8 However, why Dart would have searched for an invention like the elevators is made clear when examining the details of how grain products were handled in the early days of the Erie Canal. Boats traversing Lake Erie could not fit into the canal, meaning that all grain products had to be unloaded and then reloaded by human labour onto canal vessels.9 Therefore, the massive amounts of grain that would be sailing into and out of Buffalo would be slowed by this transitional period. Consequently, the methods of grain transportation using human labour would be unable to keep up with the ever-growing demands for food production during the height of the American Industrial Revolution and U.S. expansion. Within these contexts, the invention of the Dart elevators seems almost a natural product of the period. Machines with steam-powered hearts kept the materializing body of the United States operating, their creation was an innovation, born out of what could be seen to a Buffalo man like Joseph Dart, as a necessity for his city and country's health.

Joseph Dart and the Creation of the Elevators

Joseph Dart, the titled inventor and namesake of the Dart grain elevators, was born on April 30th, 1799, in Connecticut. Known as a well-educated, motivated, and respected businessman, he was reported to have had a hand in multiple different ventures over the course of his life, including a hat factory, and the fur trade, and real estate.10 After settling in Buffalo in 1821, he would become heavily involved in the development of the city at multiple different points. Eventually, Dart would focus his attention on the grain trade as the industry quickly overtook Buffalo's economy and became its most valuable export - setting the stage for his involvement with the development of the grain elevators.

In his obituary, Dart was remembered as having "been identified with the city's growth and prosperity for over half a century, and few men did more to promote the material interests of Buffalo during this extended period of time."11 Both his life and his work reflect this sentiment, of his life being tied to a wider cultural identity; he may appear to be 19th century America's poster child for the Industrial Revolution, an Anglo-American educated man who relocated west from his birthplace in New England and found success in the birth of an undeniably Americanized industry like grain, where U.S. commercial and national interests intersect over the need for food security. However, something that set him apart for a man of his status was his dedication to bettering Buffalo for others. Instead of allowing his privileges to feed himself alone, he put immense effort into ensuring opportunities were more accessible to the larger population. This included helping establish Buffalo Girls' Academy (later renamed Buffalo Seminary), a private school for girls' education, along with establishing the Buffalo Water Works for the city to have a solidified water system.12

It is extremely telling that what Joseph Dart is remembered for almost 150 years after his death, are his efforts to develop an industry that is intrinsically human - food. When he began work on the first steam-powered grain elevator in 1842 and finished it only a year later, he stated that his motivation was rooted not just in the betterment of his beloved city of Buffalo, but for the American people. Dart goes into further detail about these motivations, explaining, "This subject has a bearing, not only on the citizens of this community, but also upon an immensely larger number of people, whose grain productions are sent, and whose bread supplies are received through our hands. In fact, whatever facilitates the movement of breadstuffs, directly affects one of the first interests of mankind."13 Dart's work even now, is a testament to the history of 19th century U.S.A., marked with postcolonial prosperity and industrial community as the country was settled by Western society. His creation of the grain elevators was meant to aid American expansion and continue to symbolize a changing period that allowed for such grand measures of invention and development. These massive structures that could house the physical substance that many Americans made their livings from, were also constructions stemming from values of independence and innovation, ones that promoted the country's increasing development.

Operation and Growth of the Elevators

Figure 2: Workmen using ropes to control marine legs, c. 1968

Though Dart had thought of the elevators, he could not make the idea a technological reality alone, leading him to seek out and partner with a Scottish-born engineer named Robert Dunbar.14 Together, the two formulated the very first steam-powered grain elevator, erecting a significant historical monument on Buffalo's shores. The original Dart elevator's most impressive feat was its elimination of human labour - instead of men having to carry the grain onto Buffalo's shores from vessels, the elevators employed a mechanized 'marine leg' as shown in figure 2,15 that was placed in the hold of the boat, moving the product through a conveyor system into massive, sealed storage bins.16 The ease and efficiency that the elevators introduced to the grain trade was an instant success for the industry in Buffalo, resulting in a race of intense development for the machines to become bigger, better, and faster at handling the exports. The original and only elevator in Buffalo in 1843 could move around 600 bushels per hour, and could store 55,000 bushels, which quickly beat out the amount that human workers could do by a wide scale.17 In comparison, by 1864, there were 27 grain elevators on Lake Erie and the Erie Canal that could store a combined total of 6 million bushels of wheat - just over 20 years of development had shown a complete reshaping of the shipping, trade, and grain industry within Buffalo.18

The invention of the elevators, their extremely prolific exports, and their reliance on steam power also meant a reshaping of the demand for labour in Buffalo and the surrounding Great Lakes cities during the mid to late 19th century. The machines' histories are intertwined with the history of the lives and workplaces of immigrants in Buffalo at the time. This was acknowledged by Dart himself, when he recounted a story to the Buffalo Historical Society in which a merchant said that he was sorry for him and his investment in reworking the grain elevators, as "Irishmen's backs are the cheapest elevators ever built."19 The work of these Irish immigrants played an important role in the operation of the elevators both before and after they were built, as decades of the grain trade were dependent on hard labour done largely by them. Many of these men, who initially were unloading the grain from the lake vessels themselves, would go on to take the role of grain shovellers within the elevators once their jobs were replaced by conveyors and steam power. Instead, they manually assisted the flow of wheat that was lifted from the boats by managing the grain and moving it onto the marine legs to be lifted into the storage bins.20 These physically demanding, often exploitative jobs that paid very little going into the 20th century, are the other side of the road from hand to mouth that Dart coined in his speech . Dart's recognition of Irish immigrants, despite being the end of a derogatory comment from one wealthy man to another, solidified their role in the American Industrial Revolution. The grain elevators represented every hand involved in the industry which had a hand in feeding the country, both physically and symbolically, as it gave people the opportunity to make something of themselves. . It cannot be ignored that the incredible supply and demand of the grain trade came with backbreaking work, memorialized in looming structures on the shores of Buffalo.

Evolution of the Grain Elevators & their Impacts

The practice of commercializing grain production by introducing steam-power (a feat which had never been done before) allowed for products made within the United States to be delivered across the world. The grain elevators would indeed boost Buffalo onto the world stage as a grain port, at their peak handling more products than London and Rotterdam while surpassing the longstanding and infamous European industrial hub cities.21 Dart's elevators brought the Great Lakes region incredible success and effectively became a pillar of constructing America towards the global sphere of influence still seen today. The 19th century Western industrialization of grain that the elevators helped bring about, changed how nations buy, trade, and consume food compared to centuries beforehand, where staple foods like grain were not easily accessible.

Just as the grain industry changed, the elevators themselves also went through multiple redesigns to keep up with the expectations made by the intense trade empires of the 19th and 20th centuries. This included searching for ways to adapt the elevators' capacities and speed of operations, as mentioned above, but also technological advancements in construction and safety measures. Namely, the materials of which the elevators were made of went through several cycles; the original elevators were constructed from wood, as it was an easily obtained and cheap material, but later changed to steel and concrete in order to better hold the weight of the grain and reduce fire risks, that claimed the lives of many structures and workers in the early days of operation.22

When Joseph Dart passed away in 1879 at the age of 80, he had lived long enough to see the expansion of his technological empire along the shores of Buffalo, with the city reaping the rewards through heavy urbanization, development, and the worldwide respect as a grain transporting capital.23 There is no one conversation that can be had about the 19th century and the Great Lakes' era of unparalleled development without mentioning Dart and his ingenious inventions of the grain elevators. The United States would not be the same country it is in the modern era if not for him and his rewriting of how the world consumed and handled grain. The impacts of this can be seen in some of the most remembered and written about periods in history - for example, during World War I and into World War II, the elevators in Buffalo would contain a total of 300,000,000 bushels of wheat as they pumped bread products into a devastated and war-torn Europe.24 Joseph Dart forever stamped a 'Made in U.S.A' label on the history of agriculture, with the road from hand to mouth crossing continents and sailing oceans in order to connect mankind to its most fundamental desire, food.

Contemporary Studies of the Dart Elevator

Figure 3: Grain Elevators along the Buffalo River, c. 2006

In the 21st century, Dart's elevators that once monopolized the port of Buffalo and the Great Lakes have fallen out of favour from their prime, and now exist mostly as memories of a busy, industrial past. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a decline in the use of grain elevators -- with multiple reasons for these changes, as the Great Lakes region continued to change over the decades and develop more efficient routes for the grain trade, as well as improved transportation systems such as highways, seaways and rail systems across Canada and the United States.25[^26] And yet, remnants of Dart's empire and the road from hand to mouth that he carved into American society still exist in Buffalo today. Pictured in figure 3 are grain elevators that have been left behind as towering silhouettes over the ports, too expensive and too dangerous to tear down. They remain as ghosts of a long-forgotten past now rusting and crumbling away.[^27] Many artists and historians alike have reflected on the structures of the grain elevators as embodying a beast-like presence on Buffalo's landscape. Additionally, and they have been the subject of many contemporary projects from heritage conservation efforts to the art and aesthetic of industrial historical buildings, photographed and memorialized as seen in SUNY graduate Ivonne Jaeger's The Grand Ladies of the Lake.[^28]

The beauty of the grain elevators cannot be equated just to their intriguing Gilded Age industrial architecture, or their profound importance to American and Canadian history. Their true legacy is based in the body: for every generation that has ever eaten U.S. grain products, and for every elevator that has held that grain inside its steel bodies, can trace their history from hand to mouth.

-

Joseph Dart, The Grain Elevators of Buffalo. Read before the Society, March 13, 1865, Cornell University Library (New York: Cornell University Library, 1865), 391-392. ↩

-

Henry H. Baxter, "Grain Elevators," Adventures in Western New York History 26, Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society (1980), 1-2. ↩

-

Lynda H. Schneekloth, Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis: Buffalo Grain Elevators (Buffalo, New York: University at Buffalo, State University of New York, 2006), 21. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 21. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Map of the Erie Canal route, 1896], map, Thomas Curtis Clarke, Scribner's Magazine 19, no. 15 (1896), 104. ↩

-

Dart, "The Grain Elevators of Buffalo," 404. ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 2. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Obituary -- Joseph Dart," The Buffalo Commercial (1879), 3. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Obituary," 3. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Obituary," 3. ↩

-

Dart, "The Grain Elevators," 391. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 25. ↩

-

Figure 2: [Workmen using ropes to control marine legs, c. 1968], photograph, Jet Lowe, Library of Congress (1968). ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 9-10. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 26. ↩

-

Dart, "The Grain Elevators," 403. ↩

-

Dart, "The Grain Elevators," 401. ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 9-10. ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 2. ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 13-15. ↩

-

Unknown Author, "Obituary," 3. ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 16-17. ↩

-

Baxter, "Grain Elevators," 17-18. ↩

-

Figure 3: [Grain Elevators along the Buffalo River, c. 2006], photograph, Lynda Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis: Buffalo Grain Elevators," (Buffalo, New York: University at Buffalo, State University of New York, 2006), 45. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 45-65. ↩