The White Hurricane of 1913:

A Storm's Wrath on Buffalo and Beyond

Lauren Jackson

Buffalo - 2025

The Great Lakes Storm of 1913, infamously known as the "White Hurricane," stands as one of the deadliest maritime disasters in North American history. This catastrophic storm not only disrupted shipping and trade operations at vital ports like Buffalo, but also claimed numerous vessels and lives, leaving a lasting imprint on Great Lakes maritime practices and community resilience. A devastating combination of hurricane-force winds, towering waves, and blizzard-like conditions wreaked havoc across the region, claiming over 250 lives and sinking at least 12 ships.1 These events catalyzed lasting changes in maritime safety regulations, navigation practices, and weather forecasting, permanently altering the future of shipping on the Great Lakes.

The Storm's Formation and Unparalleled Strength

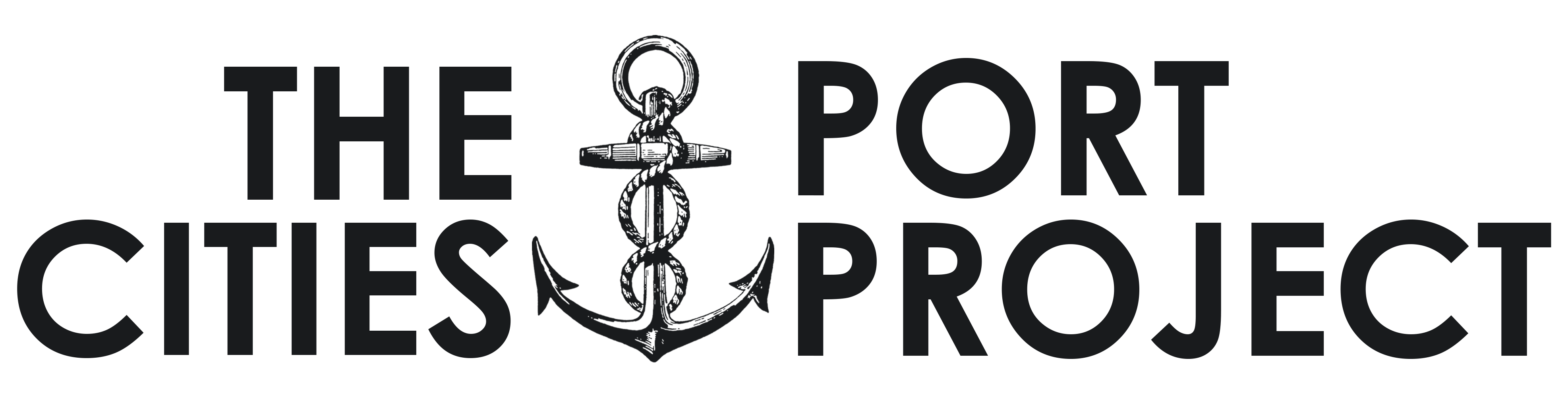

In 1913, meteorologists relied on basic instruments such as barometers and telegraphs to monitor weather patterns, but these tools provided limited insight into rapidly developing storms. Forecasts were communicated through telegraph lines and local newspapers, meaning many sailors received delayed or incomplete warnings. As a result, mariners set sail unaware of the deadly storm brewing on the horizon. The storm itself was the result of a rare and volatile atmospheric collision, cold Arctic air from Canada clashed with warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, giving rise to a deadly extratropical cyclone. As this powerful system developed on November 7, it rapidly intensified over the following three days, unleashing hurricane-force winds exceeding 70 miles per hour and waves towering over 35 feet 23 over all the Great Lakes, which is represented in figure 1.4 Heavy snowfall further compounded the danger, reducing visibility to near zero and leaving vessels blind to the hazards ahead. As the storm covered the lakes, it transformed them into a chaotic and deadly maelstrom, bringing widespread destruction and loss of life.

Figure 1: Weather map illustrating storm's wave heights in 1913.

The Port of Buffalo

The Port of Buffalo, as one of the busiest on the Great Lakes, was significantly affected by the White Hurricane. During the period from 1910 to 1915, the Port of Buffalo was a pivotal center for commerce and industry, significantly contributing to the region's economic prosperity. Strategically located at the western terminus of the Erie Canal and at the confluence of the Buffalo River and Lake Erie, the port facilitated the efficient movement of goods between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean. On a typical day in September 1910, thirty-one ships arrived in the harbour, delivering commodities such as lumber, livestock, pig iron, corn, flour, barley, and rye, with total shipments exceeding one million tons.5 This busy port highlights its role as a crucial hub for both raw materials and manufactured goods, reinforcing Buffalo's position as a dominant industrial and transportation center in the early 20th century. The thriving trade network not only supported local industries but also connected the Midwest to Eastern markets through an intricate system of waterways and railroads. By efficiently facilitating the movement of goods, Buffalo became a key player in regional and national economic expansion, solidifying its importance within the Great Lakes shipping industry.

However, this thriving port came to a sudden standstill as a powerful storm rolled in. The winds intensified, reaching speeds of 55 mph, turning the lake into a dangerous, churning force that made navigation nearly impossible. Ships struggled to maintain control of the violent gusts, and many were left stranded or damaged. The storm brought torrential rain and flooding, particularly in areas near the canal and Scajaquada Creek, which were crucial for transporting goods to and from the port. 6 Rising waters overtook streets, submerged sections of the subway system along Niagara Street, and disrupted rail connections, paralyzing movement within the city. Businesses reliant on steady shipments of coal, steel, and grain faced immediate setbacks as transportation ground to a halt. The loss of Marconi communication lines only worsened the situation, leaving weather forecasters and mariners without critical updates and increasing the danger for vessels attempting to reach Buffalo's harbour.7

The Tragic Fate of Light Vessel 82

Amidst the chaos and destruction, one vessel remained steadfast in its duty, Light Vessel 82. Stationed off Point Abino, LV-82 served as a crucial beacon for ships navigating the treacherous waters leading into Buffalo Harbor.8 Built in 1912, the 95-foot steel-hulled lightship was designed to withstand the Great Lakes' harsh conditions, equipped with a powerful beacon and a steam-powered foghorn to guide vessels safely into port. Positioned at a critical point along Buffalo's maritime routes, LV-82 played an essential role in ensuring the safe passage of ships transporting coal, steel, grain, and other vital commodities that fueled the city's industrial expansion. As the storm intensified, LV-82 remained anchored in its designated location, its crew battling the elements to keep the warning lights operational. Despite their efforts, the relentless winds and surging waves ultimately proved too powerful. The vessel was ripped from its mooring, tossed violently by the storm, and eventually disappeared beneath the lake's surface. All six crew members aboard LV-82 perished. Experts surmised that LV-82 went down on November 10, when the storm reached its zenith. No whistles or flares, or any other signs of distress were observed from the direction of the vessel. A year later, the body of Chief Engineer Charles Butler floated to the surface, but the bodies of other crew members were never found.9 In 1914, LV-96 took over the Point Abino station and in May of that year, divers located the wreck of LV-82 two miles off station in 63 feet of water. Figure 2 includes a photo of Light Vessel 82.1011

Figure 2: Light Vessel 82, n.d.

C.W. Elphicke: A Steamer Claimed by the White Hurricane

The tragic loss of Light Vessel 82 was not the only maritime disaster to unfold as the White Hurricane ravaged the Great Lakes. Just weeks earlier, another vessel, the C.W. Elphicke, had already fallen victim to the lake's merciless conditions. A 273-foot wooden freight steamer, the C.W. Elphicke, illustrated in figure 3, was a key player in the bustling trade network that connected industrial centers across the Great Lakes.12 On October 21, 1913, the vessel departed Fort William, Ontario, fully loaded with flax bound for Buffalo, New York. As it made its way across Lake Erie, the weather quickly deteriorated, with howling winds and rising waves making navigation increasingly perilous.13 Amid the worsening conditions, the C.W. Elphicke reportedly struck a submerged obstruction near Long Point, Ontario, a notorious hazard for ships traveling along this route. The impact severely damaged the hull, forcing the crew to take immediate action. With no other options, they managed to beach the vessel near the Long Point Lighthouse, hoping for a chance at salvage once the storm subsided. However, the White Hurricane had other plans. In early November, as the historic storm reached its peak, hurricane-force winds and massive waves pummeled the C.W. Elphicke, tearing apart the already crippled vessel.14 Before any salvage operation could take place, the ship was declared a total loss, swallowed by the relentless storm. Fortunately, no lives were lost in this incident.

Figure 3: The C.W. Elphicke, n.d.

Eyewitness to Disaster: Sailors and Survivors Recall the Storm

Sailors and eyewitnesses who endured the storm described it as a nightmarish battle against nature's fury. Captain James B. Watts featured in figure 4,15 a veteran of over 33 years on the Great Lakes, recalled waves crashing over his vessel with the force of 'hundreds of cannon blasts' sweeping across the decks and threatening to tear ships apart.16 He exclaims that looking into the wave troughs with fear was like looking far down into a seething valley during an upheaval of nature. Crews aboard doomed vessels reported seeing towering walls of water, 'like mountains of moving dynamite,' swallowing ships whole. Despite storm warning flags being raised, many captains underestimated the storm's ferocity, leading to disastrous consequences.17 Survivors spoke of the relentless winds that howled like 'screaming demons' and ice that formed so quickly it sealed lifeboats in place, leaving sailors with no escape. Reports

Figure 4: Captain James B. Watts, 1905.

from the time detailed the harrowing experiences of those stranded at sea, many of whom clung to wreckage for hours in freezing temperatures. In the aftermath, shipwrecks littered the Great Lakes, with bodies washing ashore days later, serving as haunting reminders of the storm's deadly force.

The Aftermath: Buffalo and Its Neighbouring States

The immediate aftermath of the storm was one of chaos and destruction, as described in firsthand newspaper reports from the time. These accounts provide a direct glimpse into the widespread devastation, painting a picture of a region struggling to recover from one of the most powerful storms in Great Lakes history.

The destruction was even greater than initially estimated. Communication lines were down in multiple directions, making it impossible to assess the full extent of the disaster. Buffalo was hit particularly hard, but the storm's impact extended far beyond, reaching cities like Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Cleveland. The blizzard paralyzed transportation networks, burying trains in deep snowdrifts and leaving entire regions cut off from vital communication. The storm's reach was so vast that even Jacksonville, Florida, experienced unusual temperature drops, with records showing a plunge to 43 degrees.18

The economic toll was staggering. An estimated $1 million in damage was inflicted on shipping interests across the Great Lakes. Piers, breakwaters, and boathouses were destroyed, while hundreds of small craft were wrecked.19 More than 50 steamers sought shelter between Whitefish Point and surrounding areas, while others lost their anchors and were left adrift. Sailors and life-saving crews agreed that the storm was among the worst ever seen, breaking records for that time of year. The damage was not confined to maritime losses, crops were frozen, houses and factories were wrecked, and businesses faced severe disruptions. Figure 5shows the damage to roads and infrastructure, where roadways from northern to southern Ontario were blocked with at least half a meter of snow and ice.[^20]

Figure 5: Damage from the White Hurricane, n.d.

Buffalo's lake and riverfront suffered immense destruction, with the storm's winds reaching a maximum velocity of 72 miles per hour. The force of the blizzard sank six boats in Black Rock Harbour Channel, including three large cabin cruisers, a tug, and other valuable powerboats. Rail and steamship services came to a standstill, with trains from the west arriving anywhere from one to ten hours late. The breakdown of communication networks further complicated the crisis. Telephone and telegraph lines were razed, forcing messages to be rerouted through Washington and St. Louis before reaching their destinations. A critical power transmission line between Niagara Falls and Buffalo was also damaged, leaving only a few streetcars operational in the morning, further straining the city's already struggling infrastructure.[^21]

The Great Lakes Storm of 1913 left an indelible mark on maritime history, claiming numerous lives and vessels, including Light Vessel 82 and the C.W. Elphicke. The storm's destruction, particularly in Buffalo, exposed significant vulnerabilities in the region's infrastructure and communication systems, forcing lasting changes in maritime safety. The aftermath of the storm, with widespread devastation across the Great Lakes, demonstrated the region's need for improved preparedness and reinforced the ongoing risks that nature's power could unleash upon maritime trade and local communities.

-

Author Unknown, "The Great Lakes' 'White Hurricane' of 1913," The Detroit News, Nov. 12, 2016. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Isaac M. Scott, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, n.d. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Weather map illustrating wave heights in 1913], map, National Weather Service (2013). ↩

-

Chuck LaChiusa, The History of Buffalo: A Chronology, n.d. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "All Wires Down, Western Storm Sweeps into Buffalo," The Buffalo Times, Nov. 10, 1913. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "All Wires Down." ↩

-

Patrick Murphey, The Loss of Lightship No. 82 -- Spring 1975, Inland Seas, National Museum of the Great Lakes, n.d. ↩

-

Lt. Daniel C. Banke, The Long Blue Line: Buffalo's "White Hurricane" and the final house of Light Vessel 82, United States Coast Guard (2022). ↩

-

Figure 2: [Light Vessel 82, n.d.,], photograph, Clinton News Record, Nov. 10, 2022. ↩

-

Figure 3: [The C.W. Elphicke, n.d.,] Georgann and Michael Wachter, "Erie Wrecks East: A Guide to Shipwrecks of Eastern Lake Erie," Apr. 1, 2000. ↩

-

Author Unknown, Lake Erie Shipwreck Map "C" and Index, Alchem Inc. n.d. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Lake Erie Shipwreck." ↩

-

Figure 4: [Captain James. B Watts, 1905], photograph, GG Archives, 1905. ↩

-

R. Dribble, "Terror on the Great Lakes -- 251 Died in 1913 Storm," Buffalo Evening News (1960). ↩

-

Dribble, "Terror on the Great Lakes." ↩

-

Nick Walker, "The White Hurricane," Canadian Geographic, Sep. 30, 2013. ↩

-

Walker, "The White Hurricane." ↩

-

Figure 5: [Damage from the White Hurricane], photograph, Canadian Geographic, Sep. 30, 2013. ↩

-

Walker, "The White Hurricane." ↩