La Griffon:

La Salle's 17th Century Voyage and French Ambition

Jayden Van Tuyl

Buffalo - 2025

Throughout the latter half of the 17th century, European powers were conquering land, establishing settlements, and expanding their colonies throughout the New World. Leading up to this period in history, all settlement and exploration within the Great Lakes was done by canoe along the shore.1 However, this changed with the expansion of French trade and exploration. Through the construction of the vessel La Griffon, La Salle provides a path which one can follow to answer the question about how the construction, journey, and return voyage of La Griffon, reflects the ambitions of the French in the New World.

French ambition in the New World, along with Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle's interest in trade and Western exploration, ultimately led to the construction of La Griffon for the Upper Great Lakes. The ambition of both La Salle and France began with permission from the king for La Salle to further explore the mouth of the Mississippi River up to the Gulf of Mexico.2 To start this journey of ambition and exploration, La Salle was granted the proprietorship and governorship over Fort Frontenac in 1675.3 La Salle's ambition for constructing a vessel was for the personal economic advantage of trade and expansion. While France's ambition was fueled by several elements.

France's ambition to construct the first vessel to sail on the Upper Great Lakes was formed through the need to control the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes route in the New World. By obtaining control over this route, the French would be able to move further west and move goods to Europe at a faster rate than their other European competitors.4 Not only was trade of high importance to French ambition, but so was the need to solidify France as a major colonial power in North America. The French saw the conquering of the Great Lakes as a foothold for Western expansion. This need for a foothold for expansion led to the ambition of conquering the Great Lakes through the construction of La Griffon.5 The third reason for French ambition in North America was to secure the usage of the Mississippi River for French trade and further exploration. By conquering the St. Lawrence, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi River, the French would have the greatest influence and control over the developing New World. As a result, this would further secure themselves as a world power while economically flourishing through trade and the use of natural resources.6 France's ambition for trade and expansion directly led to the construction of La Griffon. The eventual launching and sailing of La Griffon made history as it was the first ship to be sailed across the Upper Great Lakes of Erie, Huron, and Michigan and the third European vessel constructed for the Great Lakes trade.7

Journey to the Construction site

La Salle returned to the New World and arrived at Fort Frontenac in 1675 to create a plan to fulfill the ambitions of France. To prepare for his arrival at various stops throughout the journey ahead, La Salle sent out men to await and make friendly relations with First Nation groups. He also instructed them to collect supplies for aid in further exploration and to collect furs to be sent back to France.8 The plan to build the vessel La Griffon above the Falls at Niagara was necessary to complete the ambitions of conquering the Great Lakes as a vessel could not sail from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie. This natural obstacle of the waterfall in Niagara was the main purpose for the construction of the vessel.9 The need for construction of a new vessel due to the terrain shows how the environment created challenges and the determination of French ambition for exploration and trade.

To succeed in the conquering of France's Great Lake passage, La Salle was accompanied by Father Louis Hennepin a member of the Recollect Order of Franciscan Monks, La Motte de Lussiere who was one of La Salle's lieutenants, Luc the pilot, Henri de Tonty who was his chief ally, and a group of skilled labourers and men.10 To prepare the construction site for La Griffon, Father Hennepin, La Motte, and sixteen men aboard La Brigantine sailed across Lake Ontario to the bottom of the Falls of Niagara. Once they arrived below the falls La Motte, Hennepin and four other French men travelled to the Seneca to give gifts, negotiate, and receive permission to construct a vessel on the land in Niagara.11 In the end, they failed to obtain the approval of the Senecas. These failed negotiations with the Seneca provide insight into the challenges of France's ambition for expansion.

La Salle, Tonty, and the pilot Luc, along with a few other men, stayed at Fort Frontenac to collect materials and supplies for the new vessel, while Hennepin and the other men departed in La Brigantine.12 On the journey to Niagara, La Salle went ashore to a Seneca village to trade for corn and to gain consent for transporting supplies around Niagara Falls.13 His journey onboard Le Frontenac to Niagara came with its challenges. The first challenge arose when pilot Luc nearly sank the boat from failing to follow orders to sail along the southern shore of Lake Ontario.14 While the second challenge arrived a few days later after La Salle had continued to Niagara on foot. The challenge arose when high winds and neglect resulted in the complete loss and sinking of Le Frontenac.15 The sinking of the vessel Le Frontenac reflects the challenges of sailing on the Great Lakes and the perseverance of French ambition.

Upon arrival at Niagara, La Salle set out to find a suitable location for construction and awaited the arrival of the vessel Frontenac with the remaining supplies for his new vessel. When news of the disaster reached La Salle, he left with some men to salvage provisions and the ironwork and returned to the construction site of his new vessel.16 The journey to the construction site of La Griffon and the challenges that arose shed light on the motivation of the French to fulfill their ambitions no matter the cost or loss of materials.

Figure 1: A late 17th-century map of Niagara and surrounding area.

Construction

To succeed in the ambitions of France, the construction of the Griffon took place on the American side of the falls. In a document authored by Hennepin, he explained that the stocks for the construction of the vessel were placed two leagues above the Fall of Niagara.17 Proof of construction in this area can be seen in Figure 1, which shows a map constructed in the late 17th century that has an inscription in French that states "Cabin where the Sieur de la Salle caused a bark to be built".18

Construction of the Griffon began in December of 1678 with a few ongoing disputes. The main issue was the loss of materials from Le Frontenac. The next dispute that hindered French ambition was the Seneca, who daily expressed their discontent with the shipbuilders.19 The constant threats from the Seneca paired with the dwindling provisions due to the sinking of the vessel Frontenac, led to the loss of motivation and ambition among the men under La Salle's employment. As a result, Father Hennepin used his weekly sermons about the glory of God and the French ambition for the expansion of the Christian colonies to remind the men of the greatness to come.20 According to Hennepin, the sermons and hunting for provisions provided the needed motivation for the shipbuilders. These ongoing disputes of threats and hunger during construction show how the ambitions of the French could easily be lost and point to the challenges of exploration and trade during the late 17th century.

An illustration of the vessel in Father Hennepin's journal in Figure 2, shows the vessel being protected by the workers from the angered Seneca.21 It is important to note that the illustration has many discrepancies compared to the actual landscape above the Falls of Niagara. These inaccuracies are clearly shown by the palm trees that are shown in the background of the image.

Figure 2: Drawing by Father Louis Hennepin of the building of the Griffon, 1679.

Through Hennepin's writings, we see that the French ambition for the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes trade passage was coming true. By the end of April 1679, the ship was launched into the water, unfinished to protect it from the threats of the Seneca. Upon launching, the ship was given the name La Griffon in recognition of the griffin that was present on the coat of arms of Count Frontenac, Governor of New France.22 When La Griffon was launched, the men chanted Te Deum. The vessel was a 40-ton, roughly 55-foot vessel.23

The French ambition of trade across the Great Lakes was nearly fulfilled as La Griffon finally set sail in August 1679; however, it was not without trouble. The pilot Luc had refused to take La Griffon up the river for fear he would be held accountable for any accident. La Salle, who was back at Fort Frontenac, received this news and decided that he would lead the vessel out of the river himself.24 Due to the rapid current of the river, men were sent to shore to pull the vessel towards the lake. Through the construction up to the launching of La Griffon, we see the motivation of La Salle and his men to set sail across the Upper Great Lakes for the ambition of trade and expansion.

The Journey

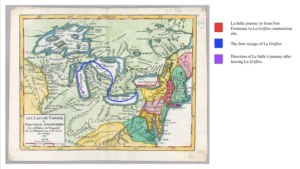

The first voyage of La Griffon began in Lake Erie and ended in Lake Michigan. This journey is shown by the blue line, below in Figure 3.25 This ambition of sailing across the Upper Great Lakes was dangerous as it had never been attempted before. As a result, La Salle and his men ran into some challenges. The first happened while sailing on Lake Erie when a thick fog settled, leaving the crew blind, but La Salle, who had seen a roughly illustrated map produced by canoe navigation years before, safely navigated them through the fog.26 By the middle of August 1679, Le Griffon sailed through both the Detroit River and Lake St Clair and into Lake Huron. While sailing through Lake Huron the crew encountered the opposition of high winds and La Salle, having less trust in his pilot, took the lead through the remainder of the journey.27 The journey on Lake Huron ended on August 27, 1679, when they reached the Bay of Michilimackinac and met up with men that La Salle had sent ahead to trade. Two of the men he had sent ahead deserted his plans, so La Salle sent Tonty out to Sault Sainte Marie to retrieve them, while he boarded La Griffon to continue through the straits to the waters of Lake Michigan. They eventually landed on Washington Island in Green Bay at the end of September 1679, with winter fast approaching. At Washington Island, La Salle and his crew met other men who were sent ahead to collect furs and wait for the arrival of La Griffon.28 The journey across three of the Upper Great Lakes and the storms that occurred reflect the dangers of French ambition on the Great Lakes and show the importance of motivation. This first voyage across the Upper Great Lakes shows the significant role that the Griffon played in fulfilling the ambitions of the French.

Figure 3: A map showing the Exploration of La Salle from 1679-1680.

The Return Voyage

To complete the return voyage of the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes trade passage, La Salle instructed for the Griffon to be loaded with the furs and any left-over provisions. He then instructed that the vessel was to be sent back under the command of pilot Luc.29 La Salle then loaded up the four available canoes with the materials to build another ship at the southern end of the lake, along with provisions for their journey. La Salle sent La Griffon out into Lake Michigan with the pilot Luc, five sailors, and a man in charge of safekeeping the cargo.

A fierce storm formed the following night, bringing great anxiety to La Salle for his ship.30 Little did he know that La Griffon would disappear to never be seen again. The disappearance of the vessel showed the French the risk of trying to attain one's ambitions. As a result, the French came to realize the cost versus risk was much too high and with La Salle headed to the Mississippi, the crew lost a leader to support their ambitions. Although La Salle continued to explore the Mississippi, there would be no further expansion or major trade for the French colony of New France. Further, the next vessel to sail across the Upper Great Lakes would sail after the surrender of New France to the British. The British now needed to travel efficiently across North America, so they constructed Navy Island in the 1760s as the first British shipyard for the Upper Great Lakes. In 1762 the British sailing vessel, the Huron, became the first vessel to sail the Upper Great Lakes eighty-five years after the disappearance of the Griffon.31 This new vessel, along with the surrender of New France resulted in the total loss of French Ambition for trade, exploration, and expansion in the New World.

In the weeks and years following the mysterious disappearance of the vessel, many assumptions have been made about what happened. La Salle, in letters to the governor of New France, states that he believes his vessel was destroyed and sunk by the pilot, with the plunder stolen.32 Other primary sources say that the Indigenous Peoples warned the pilot Luc of the dangers of the water, but not listening he persisted, leading to the sinking of La Griffon before exiting Lake Michigan. While others simply believe it was plundered by Indigenous Peoples.33 Since its mysterious disappearance, the absence of evidence for the loss La Griffon has propelled its infamy within Great Lakes maritime history. Within the last 150 years, there has been much mystery and excitement in searching for the lost vessel of the Upper Great Lakes. A wreck discovered near Birch Island was once believed to be La Griffon, but further investigation proved it was not and likely a vessel from the 19th century.34 More recently in the 21st century, a couple in Charlevoix Michigan believe they have found La Griffon near Poverty Island, but many experts doubt this is true.35

Through the story of the construction, and voyage of the vessel La Griffon, we can see a few of the many challenges of exploration and trade on the Great Lakes during the late 17th century. La Salle's story clearly outlines the time, money, resources, and labour that went into the ambitions of French colonial expansion. The vessel significantly proved that Great Lakes sailing was possible, but when it disappeared so did French ambition. The story of the disappearance remains a mystery and as far as we know there have been no true sightings of La Griffon. Hence, we are left to believe that she lies peacefully in her watery grave within the Great Lakes.

-

O.H. Marshall, The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1679. Read before the Buffalo Historical Society, February 3, 1863; and revised by the author, August 1879, 280. ↩

-

Joe Calnan. "The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon." The Northern Mariner Vol. 23 No. 3 (July 2013), 213-214 ↩

-

Author Unknown, Relation of the Discoveries and Voyages of Cavelier De La Salle From 1679 to 1681, the Official Narrative (Chicago, 1901). ↩

-

Benjamin Ford "Chapter 3 The Early History of Lake Ontario." The Shore Is a Bridge: The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Lake Ontario. College Station: Texas A&M University Press (2018), 37 ↩

-

Robert Malcomson, "To Cause Proper Vessels to be Built: 1675 to 1763," in Warships of the Great Lakes 1754-1834, Chatham Publishing (2001), 8. ↩

-

Benjamin Ford "Chapter 3 The Early History of Lake Ontario," 37. ↩

-

Joe Calnan. "The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon," 214. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Relation of the Discoveries and Voyages," 15,17. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Relation of the Discoveries and Voyages," 21. ↩

-

A. H. Greenly "Father Louis Hennepin: His Travels and His Books," The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 51, No. 1 (1957), 38-39 ↩

-

Marshall, "The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1678," 262-263. ↩

-

Marshall, "The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1678," 269. ↩

-

A. H. Greenly, "Father Louis Hennepin: His Travels and His Books," 38-39. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Relation of the Discoveries and Voyages," 9. ↩

-

Joe Calnan. "The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon,"229. ↩

-

Henri de Tonti, "Relation of Henri de Tonty Concerning the Explorations of La Salle from 1678 to 1683" (Chicago, 1898), 13. ↩

-

Louis Hennepin, "A new discovery of a vast country in America extending above four thousand miles between New France and New Mexico, with a description of the great lakes, cataracts, rivers, plants and animals : also the manners, customs, and languages of the several native Indians ... : with a continuation, giving an account of the attempts of the Sieur De la Salle upon the mines of St. Barbe, &c., the taking of Quebec by the English, with the advantages of a shorter cut to China and Japan : both parts illustrated with maps and figures and dedicated to His Majesty, K. William / by L. Hennepin ... ; to which is added several new discoveries in North-America, not publish'd in the French edition," University of Michigan Library Digital Collection (London, 1698), 62. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Late 17th-century map of Niagara and surrounding area.], map, O.H Marshall, "The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1679," 267. ↩

-

Hennepin, "A new discovery of a vast country," 62-63. ↩

-

Hennepin, "A new discovery of a vast country," 64. ↩

-

Figure 2: [The Ship-yard of the Griffon. Buffalo, 1891], illustration, Archives of Ontario (n.d). ↩

-

Hennepin, "A new discovery of a vast country," 65. ↩

-

Marshall,"The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1679," 253-254. ↩

-

Joe Calnan, "The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon," 230. ↩

-

Figure 3: [Exploration of La Salle from 1679-1680,] map, University of Notre Dame, (1749). ↩

-

Marshall, "The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1679." 280. ↩

-

Marshall,"The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1678," 283. ↩

-

Marshall, "The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1678," 286. ↩

-

Marshall, "The Building and Voyage of the Griffon in 1678," 286. ↩

-

Joe Calnan, "The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon," 214 ↩

-

Malcomson, "To Cause Proper Vessels to Be Built: 1675 to 1763," 21. ↩

-

Joe Calnan, "The Pilot of La Salle's Griffon," 218. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Relation of the Discoveries and Voyages of Cavelier De La Salle..." 157. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Another 'Griffon' Bites the Dust Schooner Days CXXXVI (136)," Toronto Telegram, April 28, 1934. ↩

-

Bill Laitner, "Doubters Abound as Charlevoix Couple Think They Found Great Lakes' Oldest Shipwreck," Detroit Free Press, May 11, 2022. ↩