Reshaping Buffalo:

The Transformation of a Waterfront City Through Trade, Decline, and Renewal

Jacob Rosa

Buffalo - 2025

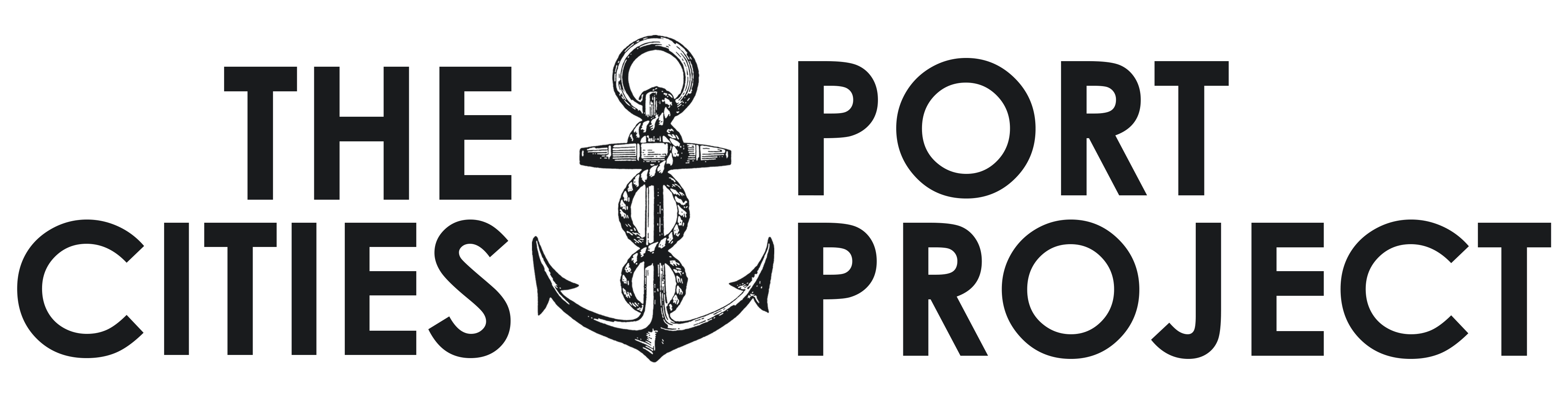

Once a thriving industrial powerhouse and a key hub for grain transshipment, Buffalo's waterfront stood as a testament to economic prosperity until shifting trade routes, infrastructural developments, and urban renewal efforts reshaped the city's landscape and future. Buffalo's waterfront and urban landscape experienced a series of large transformations throughout the twentieth century which was shaped by the city's shift from an industrial powerhouse to a post-industrial urban center. At its peak, Buffalo served as a grain transshipment hub that leveraged the Erie Canal and an extensive network of railways and grain elevators to drive economic growth. Figure 1 and 2 which depict the maps of Buffalo's port facilities from 1931 and 1940 illustrate this industrial might, showing bustling docks and silos lining the waterfront.1 However, by the 1930s, the Great Depression began to erode Buffalo's prosperity and modern shipping routes, most significantly with the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway which allowed vessels to bypass the city entirely.2 This triggered a steep decline in grain exports and associated industries.3

Figure 1: Map of Buffalo's Port Facilities, 1931.

Figure 2: Map of Buffalo's waterfront in 1940, showing the location of grain elevators and larger industries.

In response to these challenges, Buffalo employed multiple federal and state urban renewal programs that aimed to modernize its infrastructure, retain residents, and attract new investment.4 Although these efforts started significant redevelopment projects along the waterfront, they also led to social upheaval and the displacement of long-established communities. This essay argues that Buffalo's modern identity emerged at the nexus of port restructuring, urban renewal, and the adaptive reuse of historic industrial infrastructure. By examining cartographic, historical, and policy evidence, it will be argued how the city navigated a precarious transition into the post-industrial era and how the strategies employed continue to shape Buffalo's future trajectory.

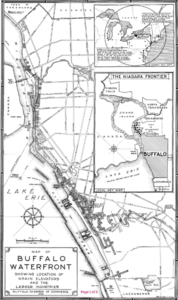

Starting from the beginning, Buffalo rapidly established itself as a linchpin for grain transshipment and industrial expansion in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as it emerged as a strategic port at the eastern edge of Lake Erie. Drawing on abundant hydroelectric power from nearby Niagara Falls and the logistical advantages provided by the Erie Canal, the city attracted mills, factories, and related services that fueled both job growth and rising urban development. This surge in industry coincided with a new form of large-scale industrial construction that met the demands of rapidly evolving technology at an unprecedented pace.5 This is illustrated in Figure 3, where an advertisement displays Buffalo's considerably large expansions in which its buildings infrastructure would be capable of handling large quantities of grain and other commodities.6 By the early 1900s, the waterfront buzzed with grain elevators, docks, and rail lines, as Figure 1 demonstrates, revealing an intricate system designed to move grain from ships onto railcars for eastern markets.7 Similarly, Figure 2 captures the city's commercial power prior to World War II, when manufacturing and transshipment operations were near their peak.8 These cartographic records illustrate how the port shaped the physical landscape with massive silos dominating the skyline and extending along the water's edge.

Figure 3: Advertisement for reinforced concrete.

During what Architectural Professor Lynda H. Schneekloth terms the city's "golden age" of grain handling, receipts increased from about 111 million bushels of wheat in 1900, to a high of 280 million by 1928.9 This reflects Buffalo's strategic location as the gateway between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic seaboard. Engineers and architects responded to these booming demands by innovating concrete grain elevators that provided enhanced storage capacity and fireproof construction.10 For several decades, Buffalo's waterfront worked as both a marvel of industrial progress and a magnet for investment. Yet, despite this prosperity, external pressures were beginning to stack. As newer trade routes and rival ports emerged, the seeds of economic turbulence were planted well before the Great Depression. When the downturn struck in the 1930s, Buffalo's manufacturing and shipping-based economy faced unprecedented stress, which set the stage for the shifts and challenges that would follow in subsequent decades.

Moving forward, as the global economy stalled in the early 1930s, Buffalo heavily felt the effects of the Great Depression due to its prior status as a prosperous industrial centre. Demand for goods and commodities plummeted, which slowed the flow of grain through the port and suppressed the city's manufacturing output.11 As Buffalo was already contending with the emerging competition from other ports, it also had to address the surging unemployment and an exiting of residents who were unable to find work. Evidence of these social repercussions can be seen in primary accounts where marginalized families established makeshift homes against the seawall in a desperate attempt to survive.12 These squatter communities depict the stark disparity between the city's former industrial might and the economic despair wrought by the downturn. While the Depression weakened consumer demand and tax revenues, infrastructural developments in the region further drained Buffalo's port economy. Improvements to the Welland Canal in the 1930s offered vessels a shorter and more cost-effective route around Niagara Falls that sidestepped Buffalo's transshipment facilities.13 Although the St. Lawrence Seaway did not officially open until 1959, these earlier upgrades to the canal network foreshadowed the larger-scale bypass that would drastically undercut Buffalo's role in grain handling and bulk transport.14

By the latter half of the 1930s, Buffalo's dependence on manufacturing and its existing shipping infrastructure offered limited resilience. While industrial facilities remained, many operated below capacity or shuttered entirely. As the city came to terms with the declining grain receipts and economic stagnation, local leaders looked towards federal relief programs and forthcoming infrastructural initiatives to keep them afloat.15 This period set the stage for future debates about how to best revive Buffalo's waterfront, an issue that would become more urgent as further trade route shifts like the opening of the Seaway pushed Buffalo to the periphery of Great Lakes commerce.

Moreover, by the mid-twentieth century, Buffalo's role as a transshipment hub was already weakened due to infrastructural improvements elsewhere. As already briefly mentioned, the most significant blow to the city's economic foundation came with the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959. This ambitious binational project developed in partnership between Canada and the United States that allowed ocean-going vessels to travel directly between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean, completely bypassing Buffalo's once-crucial port facilities. As historian Brian Hayden noted, the Seaway's construction represented a fundamental realignment of North American shipping routes while the Seaway's developers recognized that Buffalo's port suffered a considerable economic setback from the loss of transshipment traffic. As a result, the city's revenues diminished however at the same time, the municipality viewed these changes as an unavoidable reality of commercial life.16 As mentioned by Hayden, the economic consequences of this shift were immediate and severe. Prior to the Seaway's opening, Buffalo was a key grain distribution centre that handled shipments from the Midwest before they were transported eastward by rail or along the Erie Canal.17 However, once ships could sail directly from ports like Duluth, Chicago, and Detroit to Montreal and beyond, Buffalo's port traffic plummeted.18 Grain shipments through Buffalo fell from 59 million bushels in 1956-1957 to just 802,000 by 1968-1969, effectively crippling one of the city's primary economic engines.19 This shift was further compounded by Canada's greater investment in the Seaway which saw significantly more cargo passing through Canadian ports than American ones.

Despite Buffalo's long-standing opposition to the Seaway dating back to the 1920s, local leaders initially tried to maintain optimism.20 Business figures suggested that Buffalo could still thrive as an inland industrial hub by adapting to new trade conditions. Melvin Baker, chairman of National Gypsum argued in 1955 that, "smart men will see the potential here and move in, and 10 years from now Buffalo will enter a period of great growth."21 The reality was that industries tied to Buffalo's traditional transshipment role which included grain handling, steel production, and heavy manufacturing, faced a sharp decline that resulted in job losses and economic stagnation. Buffalo's experience was part of a trend that affected other Great Lakes industrial centres, but the city was hit particularly hard due to its previous reliance on grain and bulk shipments. The St. Lawrence Seaway not only diverted shipping traffic but also signaled the beginning of Buffalo's overall industrial decline that began the chain of later challenges necessitating urban renewal efforts. The next phase of the city's transformation would see federal and local policymakers attempting to compensate for these economic losses through ambitious redevelopment projects, though not always with the intended success.

To continue, as Buffalo was faced with the devastating economic repercussions of the St. Lawrence Seaway's opening and their overall industrial decline, local leaders turned to federal and state programs in hopes of rejuvenating the city. These measures included the Model Cities Program, urban renewal grants, and Enterprise Zones schemes designed to stem the outward migration of residents and stimulate new commercial investment.22 City officials envisioned modernizing the waterfront by demolishing aging infrastructure and replacing it with updated facilities that would attract businesses and residents alike. Yet these initiatives came with significant social consequences. Many older neighbourhoods deemed as "wrecked" were cleared without adequate provisions for the displaced. Goose Island offers a telling example of this as it was once a vibrant working-class district that was systematically demolished in the 1960s, forcing out long-established communities in the name of progress.23 Historian Steve Cichon recounts how planners touted a 45-acre redevelopment in downtown Buffalo that replaced wooden-frame buildings dating back to the 1860s with modern brick-and-concrete structures.24 Despite the promise of renewal, such projects often eroded local identities and severed historical ties. Although the bulldozers and new construction signaled change, the anticipated economic revival proved elusive. Some renewal projects sat partially vacant, while others never attracted the hoped-for influx of businesses. Comparisons to other Rust Belt cities like Cleveland and Pittsburgh reveal similar patterns as federal funding spurred significant demolition and rebuilding, but not always the sustainable recovery policymakers envisioned.25 Additionally, the introduction of highways and parking lots in formerly dense urban districts further fragmented communities, making pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods a relic of the past.

In retrospect, these mid-century urban renewal strategies depict the complex connection between modernization and social upheaval. On one hand, they aimed to address pressing economic issues by transforming the landscape; on the other, they disrupted the cultural fabric and displaced some of Buffalo's most vulnerable populations. Professor Alfred Price, whose research is revolved around housing for low-income households supports this ideology as it is mentioned that while the number of Black households in the area rose between 1950 and 1970, it declined in the following decade.26 This trend is particularly evident in the Ellicott neighborhood that reflects the overall pattern of neighborhood devaluation brought about by urban renewal policies.27 Further attempts at revitalization extended beyond demolition, as Buffalo gradually shifted towards adaptive reuse and heritage-conscious development in the decades that followed.

In the aftermath of mid-century urban renewal, Buffalo began re-examining its industrial heritage, particularly along the waterfront, to spark new forms of economic and cultural life. One example is the grain elevator district which was once a symbol of the city's prosperity but later left underused as transshipment declined. These concrete giants that were initially designed for massive grain storage now held potential for modern initiatives such as biofuel production, thanks to their robust structure and strategic location.28 By repurposing these monuments of industrial might, it outlines Buffalo's intent to reconcile past achievements with contemporary needs through the blending of heritage conservation and economic diversification.

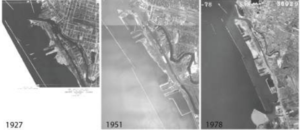

A similar trend can be seen in the Outer Harbor, where extensive industrial fill and infill projects had reconfigured the coastline. Figure 4 depicts the evolution of the Outer Harbour displaying how commercial activity once dominated the shoreline but recent efforts aim to transform much of this area into recreational spaces.29 This shift, documented in a cultural landscape report by PhD student in urban and regional planning Camden Miller, architectural historian Annie Schentag, and Professor of urban and regional planning Kerry Traynor, highlights a gradual move away from polluting industries toward public access and ecological restoration.30 Trails, parks, and boat harbours now coexist with refurbished industrial buildings that celebrate the waterfront as a community asset rather than a restricted zone.

Figure 4: Illustrates the coastal shoreline of the Outer Harbor.

Moreover, Buffalo's ongoing transformation reflects an evolving metropolitan vision that balances both innovation and respect for the city's legacy. Over the past two decades, policymakers and residents have explored approaches that include cultural tourism tied to the region's industrial architecture and multi-use developments that merge living, working, and leisure spaces.31 These strategies have attracted new residents, stimulated local businesses, and reconnected neighborhoods to the water's edge. While challenges still exist such as environmental cleanup and ensuring equitable development the city's perseverance illustrates how post-industrial centres can adapt infrastructure, heritage, and policy to create a reimagined sense of identity.

To conclude, Buffalo's trajectory from an active port city to a post-industrial environment showcases the complexities of changing trade routes, the impact of major infrastructural shifts, and the social costs of urban renewal. Once a dominant force in grain transshipment, Buffalo witnessed a rapid decline following the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway which enabled vessels to bypass its port. Federal and state renewal programs offered partial remedies but displaced historic communities, sparking debates about how best to balance economic development with social well-being. More recently, efforts to repurpose industrial infrastructure and reclaim waterfront districts signal a sustained commitment to reimagining Buffalo's identity. By capitalizing on its waterfront heritage and directing resources toward adaptive reuse, the city has laid its foundation for a sustainable future through balancing modern demands with a great respect for the physical and cultural contours that shaped its past.

-

Figure 1: [Map of Buffalo's port facilities, 1931], map, United States Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors (1931). ↩

-

Figure 2: [Map of Buffalo's waterfront in 1940, showing the location of grain elevators and larger industries], map, Brian Hayden (Washington: Tribune Content Agency LLC, 2009) 1-2. ↩

-

Brian Hayden, St. Lawrence Seaway at 50: A bypass for Buffalo's port: Seaway allowed ships to avoid a stop in Buffalo (Washington: Tribune Content Agency LLC, 2009) 2. ↩

-

Carmen J. Bartolotta, The Decline of Buffalo, New York in the Postwar Era: Causes, Effects, and Proposed Solutions, Buffalo State College (2011) 7. ↩

-

Claire Zimmerman, "Anticipating Images: Buffalo Industry under Construction, 1906-1943," Buffalo at the Crossroads: The Past, Present, and Future of American Urbanism (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020), 152-153. ↩

-

Figure 3: [Advertisement for reinforced concrete], advertisement, "Anticipating Images," 152-153. ↩

-

Board of Engineers, "Port Facilities at Buffalo." ↩

-

Buffalo Chamber of Commerce, 1940 Map Buffalo NY Waterfront (1940). ↩

-

Lynda H. Schneekloth, Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis: Buffalo Grain Elevators (Buffalo, New York: University at Buffalo, State University of New York, 2006), 32-33. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 34-35. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 41-42. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Depression Era Squatters: Outer Harbor 1930s," Western New York Heritage (n.d). ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 33. ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawerence Seaway at 50," 1. ↩

-

Bartolotta, "The Decline of Buffalo," 1. ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawerence Seaway at 50," 2. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 33. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 33. ↩

-

Bartolotta, "The Decline of Buffalo," 93-94. ↩

-

Bartolotta, "The Decline of Buffalo," 94. ↩

-

Hayden, "St Lawerence Seaway at 50," 1. ↩

-

Bartolotta, "The Decline of Buffalo," 7. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Depression Era Squatters." ↩

-

Steve Cichon, Town-Down Tuesday: Tonawanda's notorious vice district, Goose Island, Buffalo Stories and Archives (2019). ↩

-

Bartolotta, "The Decline of Buffalo," 13. ↩

-

Alfred D. Price, "Urban Renewal: The Case of Buffalo, NY," The Review of Black Political Economy 19, no. 3-4 (1991), 138. ↩

-

Price, "Urban Renewal," 138. ↩

-

Schneekloth, "Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis," 128-129. ↩

-

Kerry Traynor, Annie Shentag and Camden Miller, The Buffalo, New York Outer Harbor as a Cultural Landscape, kta preservation (2018), 46. ↩

-

Traynor, Shentag and Miller, "The Buffalo, New York Harbor," 50. ↩

-

Traynor, Shentag and Miller, "The Buffalo, New York Harbor," 51-52. ↩