The Port of Buffalo and the 1921 Hurricane:

Trading Grain, Damages and Recovery

Ivana Markotic

Buffalo - 2025

During the year of 1921, Buffalo was on track for a record-breaking year of grain sales, which was then halted due to the hurricane that travelled along the eastern coast of the Great Lakes.1 Radio messages began in Cleveland and Toledo, along with other western ports who had seen the weather developments of the storm heading towards Buffalo. These radio messages were used to not only warn those on the Buffalo ports of what was coming, but also in hopes that Buffalo could take the necessary precautions to maximize safety. 2 This hurricane created many challenges for the Buffalo community which included damaged ports, vessels, buildings, communities and the impact it had on the end of season grain sales that Buffalo was concluding. This paper will explore the history of grain trading in Buffalo and how it developed over time with the help of the Erie Canal, but more importantly how the hurricane of 1921 affected Buffalo's trading, harbour, local community and the recovery process after this tragic storm.

Buffalos harbour location allowed for easy access to Niagara, Chicago, New York and other influential ports, which gave them an edge in developing their trading reputation. Buffalo began as an exporting supply for western ports, like Cleveland, due to Buffalo's proximity and ease of access to other harbours. Buffalo began to increase the number of exports due to railway development, and industrialization occurring on their shorelines, including the inventions of the grain elevators.3 This propelled their grain market as they were able to process, produce and store more grain, which resulted in higher demands for their product. Niagara and other southern Canadian ports relied on exporting goods to Buffalo and importing goods from Buffalo, this relationship built a reliable stream of income and goods for both parties. This would help Buffalo to gain its best grain trading season to date in 1921, since then Buffalo has seen substantial rises in grain demands.4

The hurricane arrived early morning in Buffalo, on December 18, 1921. Buffalo ports received radio messages about the direction it was headed in and the strength of it as it travelled across the Great Lakes coastline.5 During the month of December trade and travel over the Great Lakes ceased, as the waters dropped in temperature making navigation on the Great Lakes difficult. Fewer vessels were present at the Buffalo harbour because of this, few were docked until the next season, while others had grain aboard waiting for morning to set sail, however the majority of this grain was destroyed in the hurricane.6 The warning received by radio provided night crews, who maintained these vessels overnight, time to prepare their ships in advance, thus minimizing the potential damages that were expected.7

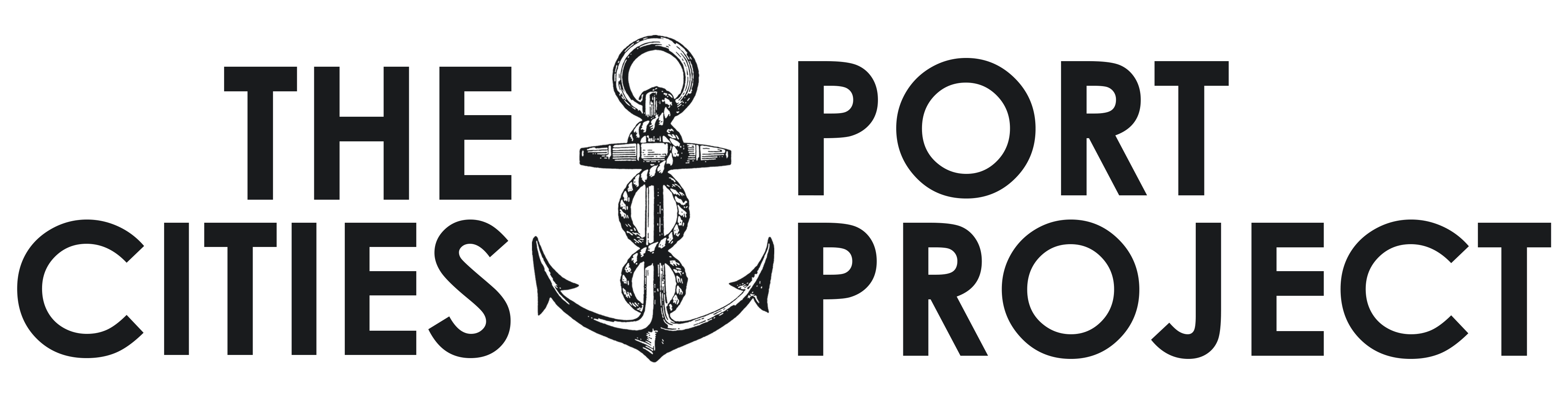

Buffalo harbour's location, which can be seen in Figure 18, displays how Buffalo's position on Lake Erie allowed for easier access to Niagara and the Erie Canal, which expanded Buffalo's trading connection and relationship with Canada and America. The map highlights how close communities and town buildings were to the shore. Upon the hurricanes arrival not only were the vessels in danger but also the communities along the shoreline. The map illustrates the port in 1921, allowing for a clearer visual as to how the hurricane traveled through Buffalo, but also the direction it went afterwards as it reached Niagara Falls.9 Figure 1 provides a glimpse into how significant the location of Buffalo's harbour is to Buffalo's trading, the ease of access for vessels and other watercrafts to enter makes it a great docking location, whilst having easy access to other large trading ports.

Figure 1: Map of Buffalo, 1921.

The early morning hurricane caused various levels of damage to the ships and vessels that were docked at the Buffalo port. At this time 97 vessels were docked, 3 of which were ferries, the remaining were all steamers. The majority of these steamers had fresh grain aboard waiting for the sail to begin in the morning to transport these goods to the desired location.10 Ship keepers or night crews typically resided on anchored vessels to ensure that everything was tied up properly and that their watercraft was safe and that everything would be ready for the next sail. As the hurricane crept closer to Buffalo the winds picked up to about 80 miles per hour, making it very difficult for the ship keepers to control their vessels to minimize damage.11 Only after the hurricane had subsided were officials able to assess the damages, and they discovered that the total approximate damage to vessels added up to 14 million and 7 million was lost in grain, (prices are relative to 1921).12 Due to the severity of the hurricane, 22 boats had bundled up and crashed into each other, which tangled up their chains making the recovery process much harder. Slowly but surely the boats become untangled and free repairs began on vessels that could be salvaged. During the off-season, boats could be repaired or replaced, which allowed for the 1922 trading season to began with minimal delays.13

Significant amounts of damage had occurred at the harbour and surrounding communities during the 1921 hurricane, resulting in half a million dollars worth of damages and one death. Trees, chimneys, windows and shanty towns were uprooted,, causing numerous damages to the community, houses and people. Furthermore, the folks who lived in these shanty towns were taken from their homes while police, firefighters and the United States coast guard, helped those in need.14 Streetcar services were put on hold until the damages could be cleared up while telephone and power lines were down throughout Quebec City and Montreal.15 The restoration process for this town was going to be a long, hard process in which they would need to work together to clean up the streets of fallen trees and rebuild their town piece by piece.16

As the boating season ended, the larger vessels would make their final deliveries before docking at Buffalo until the next season. The grain elevators near the harbour would use these vessels as storage, before transporting via truck or train.17 The nature of the Buffalo harbour meant shallow waters and lack of shelter for the vessels that docked there. Buffalo was previously hit by a smaller hurricane in 1907 which was strong enough to disrupt the breakwaters that were built on the open parts of the harbour. Subsequently, new and sturdier breakwaters were constructed in hopes that they would withstand stronger forces of wind and other natural elements.18

The hurricane began developing in Toledo, where radio reports broadcasted to eastern ports that harsh weather was on the way. The full potential of this storm was best represented in Buffalo, while previously hit cities faced minimal damage.19 The winds reached a peak of 150 kilometers per hour, causing a dramatic increase in the size and power of waves, which then disrupted the anchors and breakwaters.20 In 1921, the Weather Bureau Service ensured that weather updates were sent out more frequently, particularly along the coast of the Great Lakes. Due to its location on the Great Lakes, radio connection and size of the harbour, it made sense to make Chicago the lead distributer of urgent information.21

The development of the Erie Canal began in 1817 and completed in 1825. To celebrate this, a boat parade began in Buffalo and ended in New York, displaying the Erie Canals destined impact for trading.22 The construction of this canal provided easy access for the transportation of goods to neighbouring areas. The canal also furthered the expansion of other industries like farming, to the shores of Niagara providing more opportunities to develop their trading relationships with Niagara and New York.23 Figure 224 showcases the necessary expansions needed to adapt to the increasing demands for larger vessels to have access to the canal. As a result, this increased business availability, as more harbours wanted to make use of this critical waterway. An important piece of history to recognize here is that the Erie Canal was built over Indigenous lands, this development destroyed their land, home and way of life. The size of the Canal made it difficult to avoid developed land, the construction of the Erie Canal occurred during America's "Indian removal" federal policy, which could explain why their land was taken from them, forcing them to relocate.25

Figure 2: Illustration of the Erie Canal from Buffalo, New York.

Grain elevators proved to be increasingly useful for Buffalo as they began to receive, process and store more grain over the years. Once the grain had been processed it would be directly transported to trucks, trains and boats to be delivered, or brought to storage units, like silos.26 Numerous modifications were made to the grain elevators to enhance their structural integrity to withstand natural forces like fire, wind, rain and other potentially damaging weather conditions, as well as protecting the grain from rodents and other creatures who would soil that batch.27 Buffalo expanded their trading expeditions to Canada via the Erie Canal and railways due to the raising demand of Buffalo's grain market. These resources allowed for easier transportation which contributed to the expansion of the cities trading operations.28

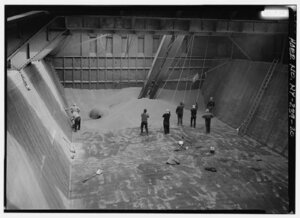

The grain elevator process is quite simple and repetitive, which helps ensure that the grain is properly processed before being sold. Trucks will bring the grain to the elevators, where the grain will be dumped and weighed before the process begins. Figure 329 depicts the next step, where the grain goes into a bucket that is then brought to the top of the elevator, it will then fall through a distributor and into another bin. The grain is weighed again before this step repeats, this can be repeated a few times if necessary, before the grain slides down and outside of the elevator into a truck or train carrier to complete the transportation of the grain.30 Depending on the season and load of grain these elevators can also serve as storage units, this resulted in larger amounts of grain being processed and prepared for transportation, responding to Buffalo's increasing grain demand. Much like silos, docked vessels would be used as storage for grain if transportation was not available or if they were being transported later. This common practice is why many of the docked vessels at Buffalo's harbour contained crates of grain, some of which were preparations for the morning sail. Ultimately this is one of the large reasons why so much grain was loss during the hurricane.31

Figure 3: The Inside of a Grain Elevator

Majority of grain elevators were constructed with wood, as it was an easy resource to acquire, although there were many drawbacks to it, for starters its flammability; external or internal fires caused great damages to these wooden elevators.32 Iron and steel were the next stages of advancement, which were seen across the Buffalo coastline, particularly by the harbour where the hurricane destroyed the two grain towers called the Mutual elevators33, which is shown in figure 4.34 More conversation occurred about which material was best for the grain elevators, seeing how harsh weather, such as a hurricane, could destroy steel or iron. Ceramic tiles and reinforced concrete were viewed as the best options to withstand fire and other dangerous occurrences, like hurricanes. Ultimately, concrete towers were favoured due to ease of cost compared to the ceramic tiles.35

Figure 4: Grain elevators on the coastline of the Buffalo Harbour.

Unfortunately, such advancements in buildings and machinery are only noted after such instances occur, in which people realize that what has been done is not safe and cannot protect itself from external elements. Furthermore, assessing the damages allows for the necessary changes to be made to increase safety and advancements of various machineries, buildings and technology. This is noted during the hurricane of 1921, where radio and weather advancements were critical during this period, as it permitted other ports to begin preparations prior to the hurricane, or other harsh weather conditions, arriving at their harbours.36 As previously noted, the breakwaters at the Buffalo harbour were already modified due to a smaller hurricane that hit in 1907. The 1921 hurricane destroyed the newer breakwaters, meaning that more planning and modifications had to go into construction to ensure it could, hopefully, withstand any future dangerous weather.37

To conclude, the 1921 hurricane that swept through Buffalo inflicted severe damages that forced the Buffalo community to unite to restore their city to what it once was. The economic development that Buffalo was experiencing this year, after the First World War, was to be a record-breaking season for Buffalo's harbour, although this hurricane prevented them from achieving this accomplishment.38 Due to Buffalo harbour's location on Lake Erie, it provided them with easy access to various ports, assisting Buffalo in recovery and developing their trading industries. Advancements were necessary as the safety measures in place for docked vessels could not withstand the powerful winds and waves of the hurricane. Technological advancements and radio messages proved to be helpful in this instance, as it provided eastern ports to prepare for the storm's arrival[^39]. The hurricane was a challenge for the Buffalo harbour, the recovery and repairing process of boats, vessels, docks, grain and the surrounding community. Buffalo displayed a strong sense of resilience and teamwork within the community to restore their city, but also to resume trading operation with minor delays in the following year.

-

Jay C. Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain: The Buffalo Hurricane of 1921 as a Demonstration of the Combined Economic Power of Commercial Carriers on the Great Lakes," The Northern Mariner 25 no. 2 (2015) 136 - 137. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Helpless Liner, 297 on Board, Defeats Storm," New York Tribune 83, no. 27,427 (1921), 3. ↩

-

Thomas, E., Leary and Elizabeth C. Sholes, Buffalo's Waterfront Arcadia Publishing (1997), 7. ↩

-

W. Dougan, Report on the Grain Trade of Canada (Ottawa: F.A. Acland, 1922), 12,70,75. ↩

-

Jay C. Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain: The Buffalo Hurricane of 1921 as a Demonstration of the Combined Economic Power of Commercial Carriers on the Great Lakes," The Northern Mariner 25, no. 2 (2015), 137. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 134. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 137. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Map of Buffalo, 1921], map, Rand McNally & Co. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Helpless Liner," 1, 3. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 137. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 137-138. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 140. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 146. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain." 139. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 134-135. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 3. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 134. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 134-135. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 137. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 137-138. ↩

-

Lakes Carriers' Association, Annual Report of the Lake Carriers' Association (Detroit: P.N. Bland Printing Co, 1921), 108. ↩

-

John W. Percy, The Erie Canal: From Lockport to Buffalo, Partner's Press (1979). ↩

-

Percy, "The Erie Canal." ↩

-

Figure 2: [Illustration of the Erie Canal from Buffalo, New York], illustration, Raphael Tuck & Sons (1907). ↩

-

Author Unknown, National Significance and Historical Context, Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor Preservation and Management Plan (2008), 2.6 -- 2.7. ↩

-

John Everitt,) A History of Grain Elevators in Manitoba: Part 2: The Architecture of Grain Elevators Brandon University, Historic Resources Branch (1992), 2. ↩

-

Francis R. Kowsky, (2007). "Part III: 1890s to 1930s: The Evolution of the Modern Elevator," Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis: Buffalo Grain Elevators, University at Buffalo (2006). ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 136. ↩

-

Figure 3: [The inside of a grain elevator], photograph, Jet Lowe, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (1990). ↩

-

Everitt, "A History of Grain Elevators," 12. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 134. ↩

-

Kowsky,"Part III: 1890s to 1930s." ↩

-

Kowsky "Part III: 1890s to 1930s"; Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 138. ↩

-

Figure 4: [ Grain elevators on the coastline of the Buffalo Harbour], photograph, Detroit Publishing Company (1910-1920). ↩

-

Leary Sholes, "Buffalo's Waterfront," 7. ↩

-

Martin, "Only the Shipwrecks Will Gain," 137. ↩

-

Martin, "Only Shipwrecks Will Gain," 134-135. ↩

-

Martin, "Only Shipwrecks Will Gain," 136. ↩