Engineering Spectacle:

The Maid of the Mist and the Commercialization of Niagara Falls

Gurman Pannu

Buffalo - 2025

The Maid of the Mist has played a pivotal role in the transformation of Niagara Falls from a natural wonder into a global tourist destination, reflecting broader themes of commercialization, labor exploitation, and environmental modification. Originally launched in 1846 as a ferry service between Canada and the United States, the vessel transitioned into a sightseeing attraction as the construction of bridges and railroads rendered ferry transport obsolete. This shift signified the growing influence of tourism and industrialization in reshaping both the economy and infrastructure of the region. However, the expansion of tourism at Niagara Falls came with significant social and environmental consequences. While tourism promised economic growth, it also brought about profound changes to labor conditions and the natural environment. The development of hotels, transportation systems, and tourist attractions depended on the exploitation of working-class labor, particularly among hotel staff, boat operators, and service workers, who endured low wages, long hours, and economic instability. Simultaneously, the physical landscape of Niagara Falls was altered to support hydroelectric production and maintain its aesthetic appeal for visitors, with Indigenous lands repurposed for industrial and commercial development, leading to displacement and cultural erasure. This essay examines how the Maid of the Mist not only symbolized the rise of Niagara Falls as a tourist destination but also exemplified the broader economic, social, and environmental consequences of commercialization. Through an examination of its role in tourism expansion, labor exploitation, and the environmental and Indigenous impacts of industrial development, this study reveals how economic ambition transformed both the natural and human landscape of Niagara Falls.

Before the construction of bridges, small boats were the primary means of crossing the Niagara River.1 . These early ferries facilitated the movement of goods and passengers between Canada and the United States, making the river a critical commercial and transportation hub. However, these vessels were often small, unreliable, and dangerous, due to the hazardous conditions of the Niagara River, highlighting the need for a larger, more powerful steam ferry. A major turning point came on May 27, 1846, when the first Maid of the Mist was launched at Bellevue, about 1.5 miles below Niagara Falls.2 Powered by two 20-horsepower engines, it became the largest steam ferry ever to operate above the Niagara whirlpool. An 1846 advertisement, published in the Daily National Pilot on May 25, 1846, emphasized both the vessel's strength and technological advancements. The ad captured the public excitement surrounding its launch, noting that a large crowd and a band of music attended the event.3 While the primary purpose of the Maid of the Mist was ferrying passengers across the river, the advertisement also hinted at its potential wartime use, stating that while it could "easily run down to Lewiston," it could never return, highlighting the dangerous currents and treacherous waters of the Niagara River.4

As infrastructure expanded, the need for ferry services declined, forcing the Maid of the Mist to adapt. The completion of the Niagara Suspension Bridge in 1848 drastically reduced demand for water transport, forcing the Maid of the Mist to pivot toward sightseeing tourism. However, before it could fully establish itself as a tourist attraction, disaster struck. On January 7, 1851, the Maid of the Mist sank while moored for the winter at Bellevue. Initially believed to be "beyond the reach of casualty," the vessel was overwhelmed when heavy snow accumulated on its decks, causing it to tilt, taking on water, and sinking in 20 feet of water.5 Despite its short but impactful career, the Maid of the Mist had already developed a reputation for daring voyages, thrilling thousands of visitors by bringing them closer to the falls than ever before. While some questioned its safety, most marveled at its bold navigation through the treacherous waters of the Niagara River.

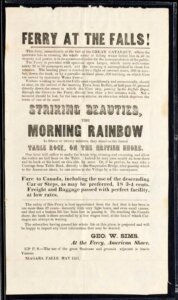

Even after the sinking of the first vessel, the brand of the Maid of the Mist persisted, evolving into a full-fledged tourist experience. Figure 1 shows a handbill from 1851 which reassured passengers of the ferry's safety, emphasizing that it had been in use for over 40 years without a single human life lost.6 The handbill outlined the standard itinerary, which included a stop at Table Rock on the Canadian shore, allowing visitors an hour to explore. Then, passengers had the option to return on the ship or take a carriage to the Suspension Bridge. The journey lasted approximately 15 to 20 minutes, with fares set at 18¾ cents. By framing the Maid of the Mist as both an adventure and a safe, well-established attraction, the advertisement reinforced its status as a must-see experience at Niagara Falls.

Figure 1: Ferry Handbill, 1851.

As the tourism industry grew, economic and social pressures increased. In 1861, the Maid of the Mist was sold to a Canadian company due to financial difficulties and the impact of the American Civil War.7 However, the sale was conditional upon its successful delivery to Lake Ontario, requiring a treacherous 5 km journey through the Great Gorge Rapids, the Whirlpool, and the Lower Rapids. The Niagara River posed extreme risks for any vessel navigating its waters. It consisted of multiple sections of dangerous rapids, with the Great Gorge Rapids leading into the Whirlpool, where swirling currents created unpredictable turbulence. Beyond the Whirlpool, the Lower Rapids carried some of the fastest-moving waters of the river, making navigation almost impossible for standard vessels.8 The sheer force of these rapids could tear apart wooden boats, making the delivery of the Maid of the Mist an unprecedented challenge. The responsibility fell to 53-year-old Captain Joel Robinson, who, on June 6, 1861, took command of the vessel alongside his assistant, McIntyre. As they entered the rapids, violent waters crashed over the deck, tearing the smokestack from the boat and nearly overwhelming them.9 Despite the immense danger and the force of the currents, Robinson remained steady, guiding the vessel through the treacherous waters with extraordinary skill and precision. His successful navigation made him the first person to complete such a journey, a feat that cemented his place in Niagara Falls' history.10

The launch of the Maid of the Mist IV in 1892 on the American side, marked this final shift from transportation to tourism. By this time, bridges and railroads had eliminated the need for ferry services, and the Maid of the Mist had been redesigned to cater exclusively to tourists. The vessel provided an up-close experience of Niagara Falls, offering visitors a dramatic, thrilling encounter with the cascading waters. This transition cemented the Maid of the Mist as a key player in Niagara Falls' tourism boom, ensuring its legacy as one of the most iconic ways to experience the falls. By the end of the 19th century, the vessel had become a symbol of both adventure and spectacle, continuing to draw visitors eager to witness the power of the falls firsthand. Passengers can be seen boarding the vessel in figure 2, while crew members prepare for departure.11 The American flag flies at the bow, emphasizing the boat's national identity and its role in Niagara's tourism industry. In the background, buildings on the cliffs of Niagara Falls highlight the increasing urbanization and commercialization of the area.

Figure 2: Maid of the Mist, U.S.A, 1901.

By the mid-19th century, Niagara Falls had transitioned from a natural wonder into a highly commercialized tourist destination, driven by industrial expansion and infrastructure development. The introduction of railroads and the completion of the Niagara Suspension Bridge in 1855 dramatically improved accessibility, leading to a surge in visitors. The Industrial Revolution further fueled this transformation, as advancements in steam power and hydroelectric energy attracted industries to the region. The availability of cheap electricity spurred economic growth, creating job opportunities that drew workers and their families to Niagara Falls. As the city rapidly urbanized, the rise of hotels, amusement parks, and recreational facilities catered to the growing influx of tourists, solidifying Niagara Falls as a premier destination.12

Tourism in Buffalo, Niagara Falls evolved in distinct phases, shaped by class dynamics and expanding transportation networks. In the 1820s--1840s, the falls primarily attracted wealthy elite travelers, who embarked on Grand Tours like European aristocratic journeys.13 These visitors stayed in luxury hotels, took carriage rides to scenic viewpoints, and traveled via steamships along the Erie Canal. However, as transportation networks expanded, tourism became increasingly accessible to the middle class. With the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the expansion of rail networks, middle-class tourism flourished. By the 1850s--1870s, affordable package tours---including transportation, meals, and accommodations---enabled more people to visit Niagara Falls. The railway industry aggressively marketed the falls as a must-see destination, contributing to an influx of visitors. By the 1880s--1920s, tourism underwent another transformation, shifting towards mass tourism as automobile travel further expanded accessibility. The introduction of automobiles and improved road networks made travel more available to the working class. Factories began offering paid vacations, allowing industrial workers to travel, further expanding the tourist demographic. During this period, Niagara's tourism industry became highly commercialized, with entertainment attractions emerging to meet the demands of an increasing number of visitors; side shows, wax museums, and amusement attractions emerged to entertain large crowds. By 1860, Niagara Falls had the highest number of hotels per area in the United States, underscoring its importance as a leading travel destination.

However, the rapid growth of tourism placed immense financial and operational pressure on businesses. In response, companies adopted cost-cutting measures at the expense of workers. While visitor numbers increased, shorter stays and fluctuating demand caused financial instability for hotels and attractions, leading to declining profits.14

As tourism flourished, the industry relied heavily on low-wage laborers, who endured long hours, poor working conditions, and economic instability.15 Census records from Cataract House Hotel in 1860, reveal that over 100 live-in workers were employed, primarily as waiters (mostly Black men) and domestic staff (mostly white women). By the 1880s, many hotels eliminated live-in staff, forcing workers to move into overcrowded boarding houses, which increased their financial instability. The seasonal nature of tourism further worsened these conditions, making employment unpredictable and financially unstable. By 1880, the number of live-in hotel workers had declined significantly, reflecting a shift toward cash wages instead of providing room and board. This change effectively cut worker earnings, as they were now responsible for paying for their own housing and meals. At the same time, hotels implemented new cost-saving strategies that further undermined workers' financial security. Hotels adopted the European Plan, which separated room and meal costs, allowing businesses to reduce staffing needs.16 These cost-saving strategies disproportionately affected Black and immigrant workers, who faced racial and gender segregation in the industry.

While Niagara Falls symbolized luxury and leisure for visitors, it represented economic hardship and instability for the workers who sustained it. The tourism industry was built on the exploitation of service workers, whose labor provided comfort and entertainment for middle- and upper-class tourists while they themselves remained largely invisible. The disconnect between visitors' experiences and workers' realties highlights the stark class divides embedded in Niagara's tourism industry. The Maid of the Mist, despite being one of Niagara's most famous attractions, depended on low-paid crew members, including boat operators like Captain Robertson, who risked their lives navigating the treacherous waters. Tourists marveled at the spectacle, the workers ensuring their experience received little recognition or financial security. These laborers ensured that tourists could experience the falls up close, yet they remained underpaid and largely overlooked. As Niagara Falls' tourism industry expanded, so did the divide between visitors and workers. While wealthier tourists enjoyed luxurious hotels, package tours, and exclusive entertainment, those working behind the scenes---waiters, maids, and boat operators---endured exhausting work conditions, long hours, and meager wages. By the 1920s, Niagara Falls had evolved into a popular working-class vacation spot, but for many service workers, the growing tourism industry only deepened their economic struggles.

Niagara Falls, once a symbol of untouched natural beauty, has been extensively altered to serve tourism, hydroelectric production and industrial expansion. The region's physical landscape was reshaped to maximize economic output, while Indigenous lands were repurposed for railroads, factories, and commercial attractions. These transformations were not passive changes but deliberate efforts to commodify the natural landscape for financial gain. Driven by economic ambition rather than environmental preservation, these changes fundamentally altered both the waterscape of the falls and the cultural identity of the region.

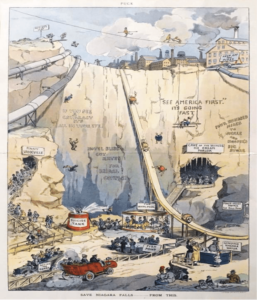

Figure 3: "Save Niagara Falls," 1906.

Figure 3 shows a satirical cartoon published in 1901, that warns against the future commercialization of Niagara Falls, showing it transformed into a chaotic amusement park filled with factories, gimmicky attractions, and reckless tourism.17 The exaggerated imagery---smoke-spewing industries, a roller coaster into the gorge, and a "Suicide Tank"---highlights concerns that the falls would be stripped of their natural beauty and turned into a man-made spectacle. The caption, "Save Niagara Falls---From This," reflects public fears that economic greed would destroy the landmark. The cartoon also hints at the growing competition between the United States and Canada to develop the falls for tourism and industry, foreshadowing the race to exploit the falls for hydroelectric power and commercial gain. The cartoon shaped public perception by using satire to emphasize the dangers of unchecked commercialization, warning that Niagara Falls could lose its natural grandeur to industrial and tourist exploitation. By portraying an exaggerated dystopian future filled with smoke, gimmicks, and reckless attractions, it foreshadows issues with environmental preservation and responsible development.

As tourism grew, so did the desire to control Niagara Falls for both spectacle and economic utility. The 1950 Niagara Diversion Treaty authorized the construction of control dams, weirs, and sluices to regulate the flow of water, ensuring that the falls maintained a dramatic and visually appealing appearance for visitors.18 By 1957, the International Niagara Control Works further manipulated the falls' structure, adjusting scenic flow rates to enhance their tourist appeal while redirecting vast amounts of water for hydroelectric production. These interventions significantly altered the natural hydrology of the region, reducing the original flow of water over the falls. As a result, up to 75% of the water that once naturally flowed over Niagara Falls is now diverted through tunnels and power plants, reducing the volume of the falls to a controlled performance. Engineers went so far as to redesign the crestlines and excavate flanks to make the falls appear more symmetrical and visually striking, further reinforcing the notion that Niagara had become an engineered spectacle rather than a natural wonder.19 Although government officials framed these interventions as conservation efforts, their primary purpose was to optimize hydroelectric output while maintaining the illusion of natural beauty for tourists.20

By the 1970s, Niagara Falls had become as much a symbol of industrial pollution as it was of natural beauty. Decades of unchecked industrialization, waste disposal, and hydroelectric expansion led to severe environmental degradation. This environmental damage became undeniable with the emergence of large-scale ecological disasters. The most notorious of these was the Love Canal disaster in 1978, where a nearby neighborhood was revealed to have been built on a toxic waste dump, leading to widespread health crises and forced displacement.21 The severity of the crisis prompted the passage of the Superfund Act in 1980, requiring companies to clean up hazardous waste sites and igniting broader conversations about the environmental costs of industrial expansion. Despite these environmental disasters, the economic interests tied to Niagara Falls' tourism and hydroelectric industries remained dominant, overshadowing concerns about ecological destruction. Niagara Falls had been altered not for preservation, but for profit, making it a case study in how industrial progress can come at the expense of both nature and human well-being.

The transformation of Niagara Falls was not limited to its physical landscape as it also led to the displacement and erasure of Indigenous communities who had lived in harmony with the land for centuries. The Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe Peoples originally inhabited the region, using the Niagara River as a vital resource for hunting, fishing, and agriculture.22 However, as settler expansion and industrialization advanced, these Indigenous lands were systematically taken, repurposed and commodified. As tourism and industry expanded, their lands were sold off and divided for railroads, factories and commercial attractions. The construction of the Erie Canal and expanding railroad networks accelerated settler colonialism, forcing Indigenous communities to relocate and disrupting their traditional way of life. The existing Indigenous trails and sacred sites became major transportation routes and industrialized landscapes, marking a shift from Indigenous stewardship to economic exploitation. While the names of Indigenous communities---Tonawanda, Cheektowaga, Chippawa---remain in the region, the people themselves were largely displaced.

Before colonization, Indigenous communities maintained a sustainable relationship with the land, employing advanced environmental management techniques. They lived in longhouses, practiced sustainable agriculture, and engaged in controlled burns to manage forests and maintain hunting grounds.23 These methods ensured that the land remained fertile and abundant for future generations. However, settler colonialism replaced these ecological practices with extractive and unsustainable agricultural methods. Between 1700 and 1850, European settlers replaced Indigenous farming systems with monoculture crops like wheat and rye, transforming diverse agricultural landscapes into industrialized farmland. The imposition of European property laws further disrupted Indigenous land use, dismantling communal ownership practices to privatized land. Fences, roads, and boundary markers imposed private property laws, disrupting traditional Indigenous land use.

Ironically, while settlers dismissed Indigenous land management as primitive, they simultaneously adopted many Indigenous survival techniques. White settlers learned to trap, hunt, extract maple sugar, and use traditional Indigenous transportation methods, including canoes, snowshoes, and toboggans. Despite benefiting from Indigenous knowledge, settler society continued to marginalize and displace Indigenous communities, denying them sovereignty over their own lands. The last major Indigenous resistance to Niagara's transformation came from Seneca chief Red Jacket (Sagoyewatha), who strongly opposed the industrialization and manipulation of the falls.24 Although his resistance was ultimately unsuccessful, his legacy remains a symbol of Indigenous defiance against environmental and cultural exploitation. Today, a statue of Red Jacket stands as a reminder of this resistance, but the broader reality remains---Indigenous lands were seized, repurposed, and their environmental wisdom disregarded. While Niagara Falls continues to be marketed as an untouched wonder, its transformation reflects a deeper history of environmental exploitation and Indigenous marginalization.

The transformation of Niagara Falls serves as a powerful example of how land can be exploited for economic and personal gain. What was once a natural and cultural landmark becoming a commercialized, industrialized site, altered to maximize profit rather than preserve its original integrity. The expansion of tourism and hydroelectric projects reshaped both the physical and social landscape, prioritizing economic growth over environmental preservation and Indigenous sovereignty. As tourism flourished, economic disparities widened, and the landscape was engineered to meet industrial and aesthetic demands. The control of water flow, the rise of mass tourism, and the displacement of Indigenous communities reveal how Niagara Falls was not simply developed but systematically altered to serve commercial interests. While it remains a global attraction, its transformation reflects deeper histories of labor exploitation, environmental depredation, and cultural loss. Thus, Niagara Falls serves as both a marvel and a cautionary tale. Its legacy is not just one of awe-inspiring beauty but also one of environmental and social cost. Recognizing this history challenges us to critically examine the balance between economic expansion and preservation, raising questions about how we engage with natural wonders today.

-

Author Unknown, The History of the Maid of the Mist, Niagara Falls Info (n.d). ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Launch," Daily National Pilot, May 25, 1846. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Launch." ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Launch." ↩

-

Author Unknown, "Maid of the Mist," Daily Courier, Jan. 7, 1851. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Ferry Handbill, 1851], handbill, Geo. W. Sims, Niagara Falls Handbill Collection, Brock University Archives (1851). ↩

-

Author Unknown, "The History of the Maid of the Mist." ↩

-

Keith Tinkler, Geology of the Falls, Niagara Parks, Dec. 8, 2003. ↩

-

Author Unknown, "The History of the Maid of the Mist." ↩

-

Author Unknown, "The History of the Maid of the Mist." ↩

-

Figure 2: [Maid of the Mist, U.S.A, 1901], photograph, Brock University Archives and Special Collections (1901). ↩

-

Christof Mauch and Lucy Jones, "Niagara, New York: The Second Greatest Disappointment," Paradise Blues: Travels through American Environmental History (2024). ↩

-

LouAnn Wurst, "Human Accumulations: Class and Tourism at Niagara Falls," International Journal of Historical Archaeology 15, no. 2 (2011), 255. ↩

-

LouAnn Wurst, "Human Accumulations," 258. ↩

-

LouAnn Wurst, "Human Accumulations," 256. ↩

-

LouAnn Wurst, "Human Accumulations," 258. ↩

-

Figure 3: ["Save Niagara Falls,"1906], illustration, John S. Pughe, Ottmann Lith. Co., 1906. ↩

-

Daniel Macfarlane, "A Completely Man-Made and Artificial Cataract": The Transnational Manipulation of Niagara Falls," Environmental History 18, no.4 (2013), 768. ↩

-

Daniel Macfarlane, "A Completely Man-Made and Artificial Cataract," 765. ↩

-

Daniel Macfarlane, "A Complete Man-Made," 779. ↩

-

Mauch and Jones, "Niagara, New York," 155. ↩

-

Mauch and Jones, "Niagara, New York," 146. ↩

-

Mauch and Jones, "Niagara, New York," 150. ↩

-

Mauch and Jones, "Niagara, New York," 148. ↩