Port of Hamilton in the 19th Century:

The Flow of Commodities A Timeline of Contributions to the Ambitious City

Calum Whitla

Hamilton - 2022

The Port of Hamilton saw significant improvements during the 19th century and faced economic challenges that were reflected in the flow of commodities in and out of the port. The founders of Hamilton and early governmental actions created a city that provided utilities to support and nurture the manufacturing industry, thus creating a powerful industrial centre and a functional port that surpassed all competing areas. The development of the Port of Hamilton was linked to improvements in the transportation of goods, including railways and local and distant canals which linked manufacturing centres and natural resources. A timeline of the flow of commodities in and out of the Port of Hamilton throughout the 19th century, available shipping records, government records, and other reliable sources that will be examined throughout this essay depicts Hamilton as being a manufacturing hub supported by strong shipping and rail lines.

Initially referred to as Burlington Bay, Hamilton Harbour was settled by George Hamilton and was an area unsuited for trade because it lacked a stream to support a village and was separated from Lake Ontario by a swamp.1 Hamilton Harbour saw significant changes during the 19th century and evolved from rudimentary wharves constructed by early merchants and waterfront landowners to large functional wharves supported by grain elevators and rail tracks owned by the Great West Rail Road. These improvements had the ability to support a solid manufacturing industry in Hamilton and beyond. Despite being located near Lake Ontario, Hamilton remained cut off from the main body of water by Burlington Beach– a sandbank extending across the bay and making the bay impassible. Industrious settlers unloaded cargo from lake schooners into storehouses on the beach and then loaded the cargo onto smaller vessels to transport through the bay.2 Despite the transportation challenges, leaders in Hamilton enticed investors to the city with assurances of a solid infrastructure, access to natural resources, and a growing population to supply labour.3

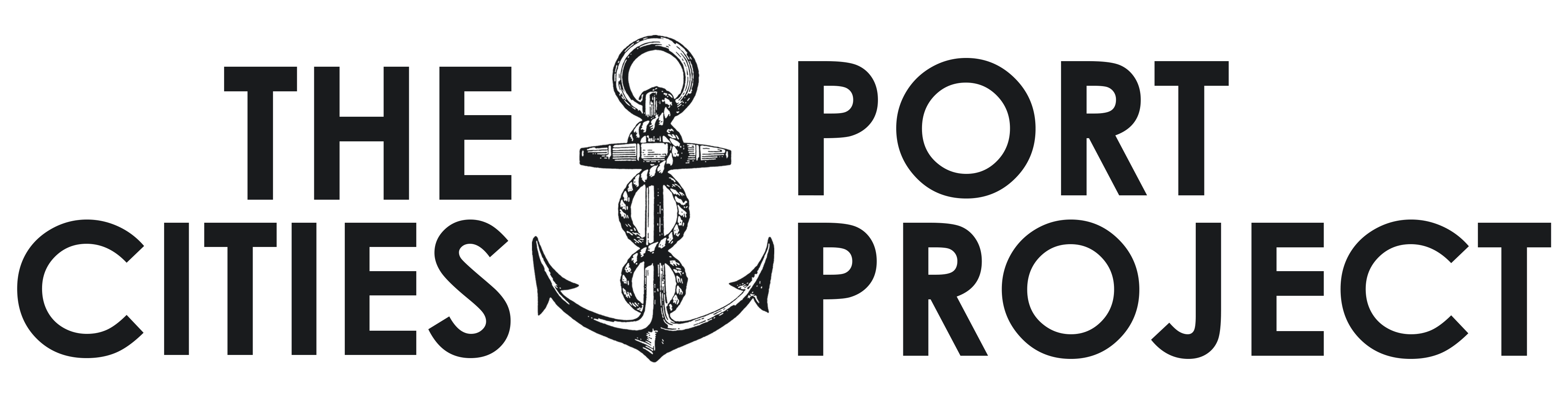

Figure 1: Map of Upper Canada- Welland Canal Area Featured

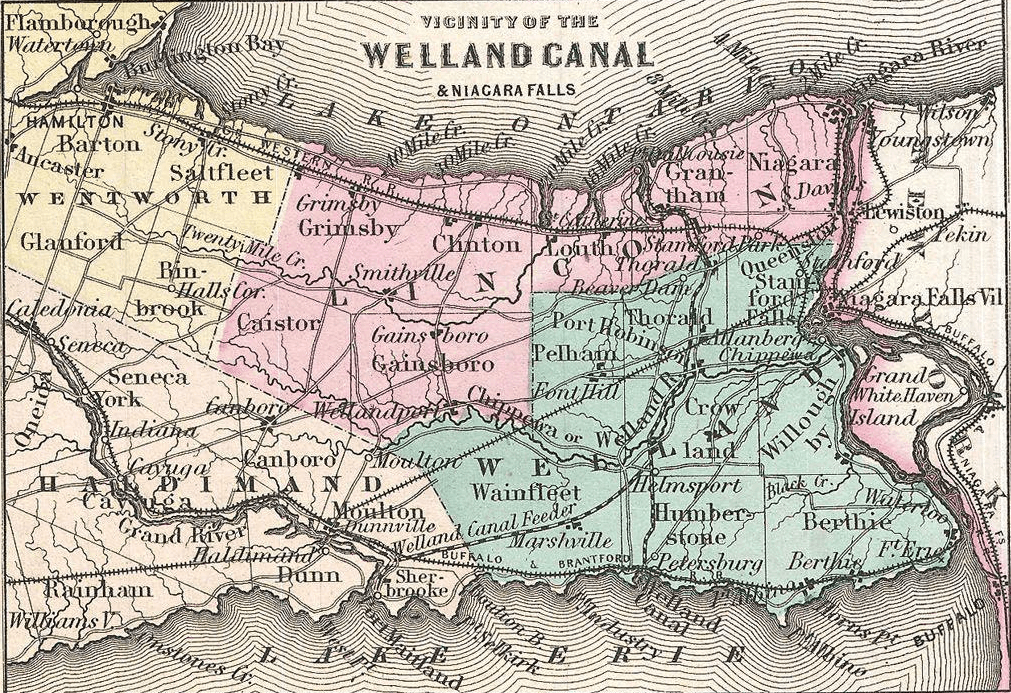

The War of 1812 brought to light the need to establish a supply chain, and the advent of steamships on Lake Ontario highlighted the need for port infrastructure to support these vessels. By 1817, various canals were being built, and the construction of the Erie Canal created completion between industries using the St. Lawrence River, as those on the Erie now had access to ports on Lake Ontario.4 The development of canals would prove instrumental in the movement of commodities through Hamilton, and in 1818, investors sought the Welland Canal (see Figure 1).5 In March of 1823, legislation was passed permitting the construction of the Burlington Canal which was completed in 1826. An exert from the Kingston Chronicle, dated July 14, 1826, offered congratulations to Sir Peregrine Maitland, Lieuntanent Governor of Upper Canada, on the partial completion of the Burlington Canal (see Figure 2).6 Hamilton continued to serve as an ideal location to transport grain to nearby farmers and mill owners, and in 1823, over 14,00 barrels of flour were shipped from Burlington Beach.7

Figure 2: Exert from the Kingston Chronicle, 1826

Development of the waterfront in the late 1820s allowed an increased flow of commodities. Potash and flour were transported, and work continued on the Desjardins, Burlington, Rideau, and Welland Canals. In 1828, Hamilton was emerging as an industry leader in shipping and supplied Oswego with grain and lumber. That same year, the Oswego Canal created a direct line from the Erie Canal to New York and challenged the monopoly held by those shipping on the St. Lawrence. The Oswego Canal allowed traders to enter New York from Lake Ontario and the Upper Great Lakes.8 Although the Burlington Canal remained incomplete, in 1829, smaller schooners could still pass with cargo of wheat and flour.9

In April of 1830, the Gore Balance reported that vessels successfully traversed the Burlington Canal and passenger transport made Hamilton accessible. In March of 1832, the Niagara Gleaner recorded that General Brock had left the Burlington Canal with whiskey, pork, and passengers.10 The early 1830s saw an increased use of the Port of Hamilton, including the influx of British immigrants and the growth of mercantile houses, granaries, and other businesses to support the population.11 By 1843, the Burlington Canal was completed, with four functional wharves, and the population of Hamilton was 2,100 and growing.12 The mid-1830s witnessed Hamilton’s first foundry, and development continued at the port.13 In July of 1836, 17,000 bushels of wheat were shipped out of Hamilton.14 The Desjardin Canal opened in 1837, making it easier for lumber, grain, and other agricultural produce to reach the port for transportation on the Great Lakes.15 Hamilton’s second foundry opened in 1838 opened up more manufacturing opportunities. Unfortunately, these years also saw some political unrest which undermined international trade.16

The 1840s witnessed Hamilton emerging as an industrial centre with small foundries producing material for sewing machine operations and farming equipment, with a population of 3446 in 1841.17 As political unrest waned, shipping on the Great Lakes resumed to normal with the advent of steam power increasing the movement of commodities. The Port of Hamilton’s waterfront continued to develop with additions of wharves leading to the increased movement of passenger and cargo vessels through the port.18 Construction of wharves continued, indicating that shipments through the port increased, with the continuing construction of the Welland Canal supporting the location. In September of 1844, the Hamilton Journal reported pig iron had arrived from Montreal and that a direct transport from Montreal to Dundas via the Desjardin Canal had been loaded with flour for a return trip. Furthermore, in 1844, the Burlington Canal saw the passage of barrels of flour, pork, wheat, lumber, and staves. By 1945, there were reports that Hamilton was rivalling Toronto in growth but needed to address the distance between the water and the business area.19 On June 9, 1846, Hamilton was incorporated as a city and witnessed continued growth. In 1847, Hamilton’s population had grown to 6832, doubling in six years.20 Commodities continued to flow, with the Clyde departing with flour, pork, and butter. The Thames also left with flour, followed shortly by two other vessels carrying similar cargo. Investments continued to grow with local businessmen purchasing steamers to transport flour directly to Lachine.21

Business in Hamilton grew, with the addition of sail-making and rigging businesses to support the shipping industry. February of 1848 heralded an early start with several shipping companies looking for business opportunities. This season also saw proprietors recognizing that they could profit strictly from freight and did not need to carry passengers, as articulated in an advertisement for the steamboat Dawn which travelled between Hamilton and Montreal. The shipping industry was also building relationships with railways and other vessels such as coordinating schedules to accommodate passengers connecting routes. An advertisement for the Telegraph established improved coordination of services with an arrival that coincided with a railway car destined to Niagara Falls and Buffalo and steamers to Rochester, Oswego, Syracuse, New York, Montreal, and Quebec.22 An article in the Dundas Warder, included in the St. Catharines Journal on May 18, 1844, referenced the Britannia as it left Dundas with flour, pork, and livestock. The completion of canals in Lachine saw vessels from Hamilton laden with flour venture straight to Quebec. However, the waterways remained treacherous with vessels from Hamilton experiencing loss, including Chief Justice Robinson which lost its wheat cargo after going ashore at Presqu’ile.23

The 1849 shipping season was strong, with vessels New Era, Magnet, City of Toronto, Eclipse, and Rochester being very active. In the summer, the New Era began sailing from Hamilton every Wednesday and Saturday to Toronto and Kingston and travelled faster than previous vessels.26 In June, the Britannia moored at the port with unspecified freight for nine different purchasers. Previously the Hibernia left the Port of Hamilton with flour, and on the same day, the Trafalgar transported boards and shingles.24 Also, in June, the propeller Free Trade arrived with freight, and the Gilmore arrived with iron and salt. The steamboats Ottawa and Hibernia arrived at the port with freight. The schooner Clyde also arrived with freight, and the Britannia left the Port with barrels of flour, ashes, butter, cheese, and whiskey from various agencies in Hamilton and Dundas. Additionally, the Free Trader left the Port of Hamilton with barrels of flour, whiskey, and butter from various proprietors. Although freight trade was solid, the Port of Hamilton also saw much immigration, creating a problem since those arriving from Montreal were without support and relied on government assistance, with speculation that Toronto and Montreal were purposefully burdening Hamilton.25

The years of 1850 to 1856 were profitable, with possibilities expanded in 1852 as the Great Western Rail Road began construction which brought employment opportunities and demand for material as they sought bids from manufacturers to construct several rail cars and bids to dredge the proposed area of the Desjardin Canal through Burlington Heights.26 The port remained extremely busy with vessels arriving and leaving throughout the season. On December 22, 1852, a steamer, the Traveller, arrived at the Port of Hamilton from Cape Vincent, New York, with two locomotives for the Great Western Rail Road. A few days later, the America also from Cape Vincent arrived with a locomotive and tender, and other essential material, including 65 pairs of trucks for the rail cars. On December 8, the Lord Elgin had left Hamilton for Oswego with a full cargo of flour.27 The year 1853, included the construction of the railway which continued to demand resources and thus saw the arrival of materials. In August 1853, a local was recognized in the Hamilton Spectator as producing rail cars for the railway and securing the sale of two cars and employing 80 men. On December 3, 1853, London, left the Port of Hamilton headed to Chatham with rails, spikes, and furniture for the Great West Rail Road. In addition to growing metal manufacturing, the Port of Hamilton saw the construction of two buildings at the foot of Bay Street dedicated to shipping grains. The system utilized gravity to move grain from street level to the wharf.28

The boom of metalwork in 1854 heralded the construction of a foundry at James Street North at Simcoe Street, called Atlas Works, consisting of a foundry, machine shops, a finishing department, a boiler shop, and a blacksmith shop.29 On October 11, 1854, the schooner Premier arrived from Montreal with two locomotives and tenders, coal, axels, pig iron, resin, and iron pipe. In December, the Minerva Cook arrived from Garden Island with rails, as merchants from afar discovered this to be a profitable commodity.30 An examination of the shipping records of the Welland Canal Register for lock three from April to August 1854 reveals the cargo entering and exiting from the Port of Hamilton (see Figures 3-4 and Tables 1-2 below).31

Figure 3: Total downbound cargo

Table 1

Welland Canal Lock 3 April 1854 – August 1854 into (Downbound) of Port of Hamilton

| Name of Vessel | Nationality | Where From | Where Bound | Number of Trips | Cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royalist | British | Erie | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Catherine | British | Erie | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Missouri | American | Erie | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Napoleon | American | Erie | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Swan | American | Erie | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Georgina | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Edith | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 2 | Coal |

| General Wolfe | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 2 | Coal |

| Antelope | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Catharine | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Maid of the West | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Sophia | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Kasciusko | American | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

Figure 4: Total upbound cargo

Table 2

Upbound Vessels – Leaving Hamilton

| Name of Vessel | Nationality | Where From | Where Bound | Number of Trips | Cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catherine | British | Hamilton | Erie | 1 | No Cargo |

| Missouri | American | Hamilton | Erie | 1 | No Cargo |

| Edith | British | Hamilton | Cleveland | 1 | No Cargo |

| General Wolfe | British | Hamilton | Bear Creek | 1 | No Cargo |

| General Wolfe | British | Hamilton | Cleveland | 1 | No Cargo |

| Antelope | British | Hamilton | Erie | 2 | No Cargo |

| Maid of the West | British | Hamilton | Bear Creek | 1 | No Cargo |

| Maid of the West | British | Hamilton | Port Robinson | 1 | Iron |

| Briton | British | Hamilton | Port Stanley | 1 | Pig Iron |

| Peregrine | British | Hamilton | Port Rowan | 1 | Merchandise |

| Mohawk | British | Hamilton | Port Rowan | 1 | Brick |

| Emblem | British | Hamilton | Chatham | 1 | Iron/Merchandise |

The import of coal was instrumental in the metal production and supported reports of increased manufacturing in this field. The heavy shipments of coal were evidence of the metal manufacturing in Hamilton and the need to fuel steamers. These records, however, only reflect goods transported through the Welland Canal at Lock 3 to Hamilton and do not reveal the records of the vessels that passed through other canals or reference points. Few commodites left the Port of Hamilton aside from general merchandise, iron, and bricks which demonstrates that there was little being sent from Hamilton to other ports through the Welland Canal (see Figures 5-6).32

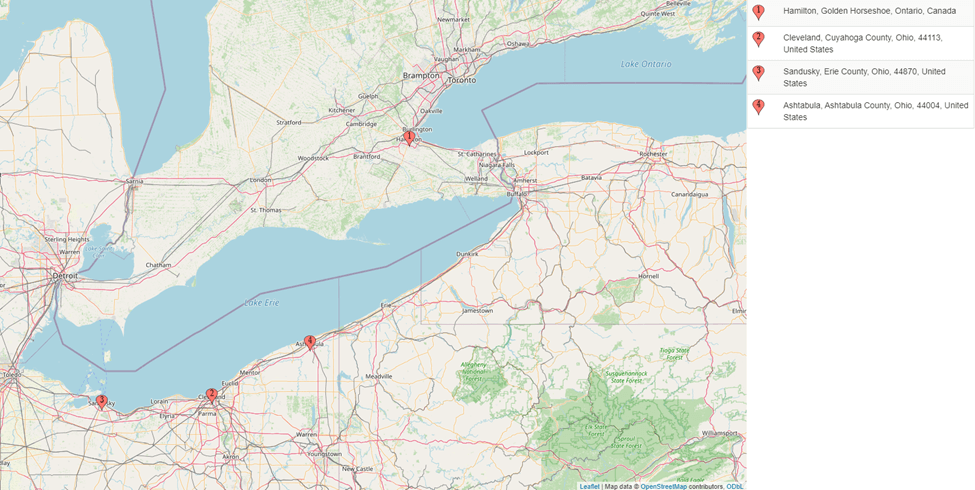

Figure 5: Map showing frequent ports of connection based off data from Table 1 and Lock 3

Figure 6: Map showing frequent ports based off data from Table 2 and Lock 3

With the continued construction of the railway and a dedicated Great Western Rail Road Warf, the Port remained active, as demonstrated by three schooners from Montreal passing through the port on June 19, 1855: the Caroline with two locomotives and pig iron, the Premier with two locomotives, pig iron, and kegs of powder, and the British Queen with two locomotives, two boilers, three tenders, wheels and axles, machinery, other supplies for the construction of rail cars, and pig iron. On July 7th and 8th, a number of vessels entered and exited the supporting industry, with coal arriving from Cleveland and other supplies directly headed to the Great Western Rail Road. Vessels leaving the port contained general merchandise, lumber, sheepskin, wheat, and stone.33

In 1856, the Great Western Rail Road continued to demand resources, and in August, Daniel Charles Gunn opened Locomotive, Steam Engine, and Forge works at Wentworth Street north of the Great Western Rail Road tracks near the Sherman Inlet. Gunn was able to sell a locomotive to the railway and committed to building more on speculation. Although the railway created demand, this was the beginning of a downturn in the shipping industry, but other resources continued to flow into the port.34 The shipping industry was about to hit a turbulent period, and on March 12, 1857, there was a train wreck at the Desjardins Canal Bridge that resulted in the loss of life and extensive damage. The waterways, however, were open by mid-April, seeing as the Boston and the Banshee passed through loaded with flour– one of them heading for Oswego. Other schooners that had wintered in the Port were loaded cargos of lumber, pipe staves, and flour.35

In 1858, the population of Hamilton was 27,500 people, but by 1861 a financial crisis had hit, and the population fell to 19,096, and dropped to 17000 in 1864. In 1869, the Port of Hamilton was active, and newspaper records reflected the highlights of industry and the flow of commodities in and out of the port. The Great Western Railway sought tenders to transport 7,000 tons of coal from Cleveland to Hamilton, including canals tolls.36 News articles reflected growth in iron manufacturing with improvement to both sailing vessels and equipment used to remove commodities from vessels. An article from the Hamilton Spectator, dated April 22, 1869, mentions the Acadia having a swinging steam crane which was as efficient as six men with relatively little expense from needed fuel. This vessel was charged with conveying a cargo of coal from the Bruce Mines to acquire a shipment of coal.37 Further supporting the idea that coal was becoming a predominant commodity in the port are the shipments arriving from Cleveland and Oswego.38 In October of 1869, grain continued as a staple, with barley and red wheat being shipped from Hamilton to Toronto, Oswego, Kingston, Chicago, and Ogdensburg. Peas were also shipped to Oswego and Montreal. The continued building of the railway saw the Bessie Baker and the Aigle De Mer arriving in mid-November with rails for the Wellington, Grey & Bruce Railway. On the same date, coal continued to arrive at the port, with barley departing for Oswego.39

Records from Welland Canal Lock 3 from June 1875 to May 1876 provide evidence of the flow of commodities in and out of the Port of Hamilton. The records show coal as a predominant cargo into Hamilton, with some vessels making regular trips and then leaving without cargo, and other vessels making the journey faster than in previous years. In the fall, vessels took barley to Chicago and Toledo which would have coincided with the harvest of the crop. Whether schooners or propeller driven, almost all of the vessels were British-owned with only a few American-owned vessels, perhaps due to higher taxation for American owned vessels (see Figures 7-8 and Tables 3-4).40

Figure 7: Total outbound cargo

Table 3

Welland Canal - Lock 3 June 1875 – May 1876 into Hamilton (Downbound)41

| Name of Vessel | Nationality | Where From | Where Bound | Number of Trips | Cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annie Falconer | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 2 | Coal |

| W.Y. Emery | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Ella Murton | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 10 | Coal |

| Gulnair | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Gulnair | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | No Cargo |

| Trade Wind | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Cecelia Jeffery | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 2 | Bar Iron |

| Undine | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 2 | Coal |

| Undine | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Iron |

| Undine | British | Cleveland | Hamilton | 1 | Stone |

| Agnes Hope | British | Ashtabula | Hamilton | 4 | Coal |

| C.H. Rutherford | British | Sandusky | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

| Mediterranean | American | Sandusky | Hamilton | 1 | Coal |

Figure 8: Total upbound cargo

Table 4

Welland - Canal Lock 3 June 1875 – May 1876 Out of Hamilton (Upbound)42

| Name of Vessel | Nationality | Where From | Where Bound | Number of Trips | Cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ella Murton | British | Hamilton | Cleveland | 10 | No Cargo |

| Gulnair | British | Hamilton | Cleveland | 1 | No Cargo |

| Trade Wind | British | Hamilton | Cleveland | 1 | Marble |

| Undine | British | Hamilton | Cleveland | 5 | No Cargo |

| Agnes Hope | British | Hamilton | Ashtabula | 4 | No Cargo |

| C.H. Rutherford | British | Hamilton | Sandusky | 1 | No Cargo |

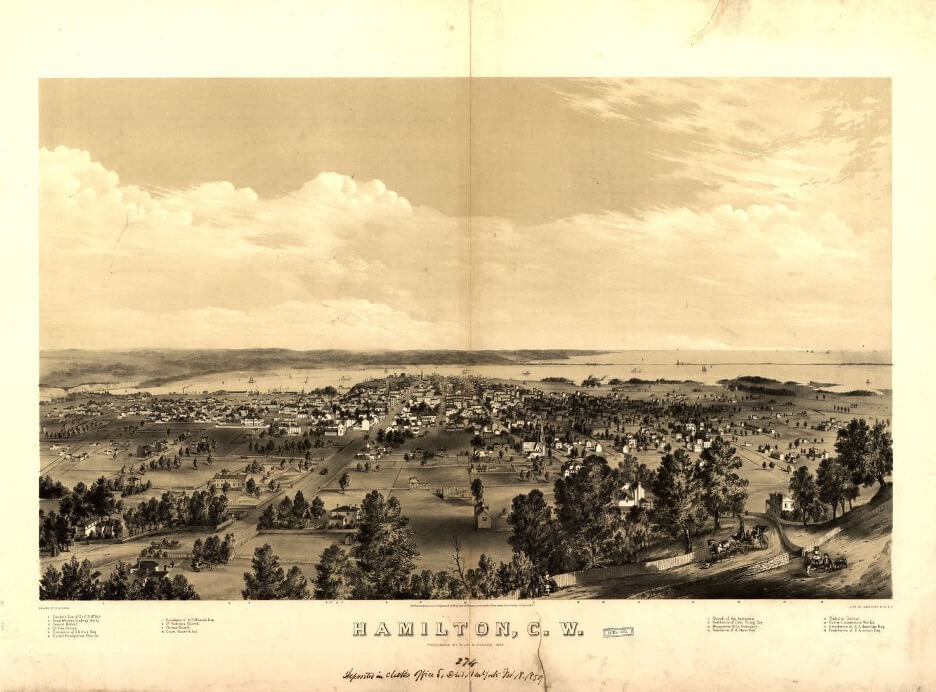

In 1876, Hamilton was a manufacturing hub with access to both shipping and rail routes and was able to provide goods throughout Upper Canada, America, and on a larger international scale. An 1876 map of Hamilton (see Figure 9) reveals the growth of manufacturing with is further supported by the volume of coal, iron, and stone entering the Port of Hamilton. The map details the expansion of industry, with textile mills, foundries, and iron works. Additionally, churches, hospitals, and schools were constructed to support the population.43 A comparison with an image from 1859 (see Figure 10) reveals the extensive growth of the city, encompassing population and industry.44

Figure 9: Map of Hamilton, 1876

Figure 10: Map of Hamilton, 1859

In conclusion, an examination of the goods transferred through the Port of Hamilton provides insight into the manufacturing industries operating at the time. Further, financial crises are identifiable as goods decreased in number, population numbers dipped, and the sale of vessels as investors attempted to recoup any losses. In the early to mid 1800s, Hamilton saw expansion through immigration from the United Kingdom and associated growth in industry necessary to support the residents. The Port saw the export of agricultural goods from the surrounding farmland and granaries and imports of merchandise and household goods for the residents. Times of prosperity, marked by the building of canals and railways, are revealed in shipping records as wharves were built or extended, ships were purchased, and vessels made journeys absent of cargo. Hamilton thus emerged through industrialization as the ‘Ambitious City’ and a rival to its neighbours such as Toronto.45

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 2- Public Works and Private Enterprise,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=S2. ↩

-

“Old Port Hamilton,” Workers’ City, accessed January 10, 2022, https://www.workerscity.ca/old-port-hamilton. ↩

-

Herbert Lister, Hamilton Canada: Its History, Commerce, Industries Resources (Hamilton, ON, 1913), 45. https://www.electriccanadian.com/history/ontario/hamiltoncanada.pdf. ↩

-

Brookes, “Public Works and Private Enterprise.” ↩

-

Brookes, “Public Works and Private Enterprise”; Figure 1: J.H. Colton, “Canada West or Upper Canada (1855),” accessed through Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1855_Colton_Map_of_Upper_Canada_or_Ontario_-_Geographicus_-_Ontario2-colton-1855.jpg. ↩

-

Figure 2: “Domestic,” Kingston Chronicle (Kingston, ON), July 14, 1826, 2. Accessed March 24, 2022, https://vitacollections.ca/digital-kingston/97160/page/2. ↩

-

Rod Millard, “Building the Burlington Bay Canal: The Staples Thesis and Harbour Development in Upper Canada, 1823-1854,” Ontario History 110, no. 1 (2018): 59–87, https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/onhistory/2018-v110-n1-onhistory03559/1044326ar.pdf. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 3- Port Hamilton, 1827,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca//documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1827. ↩

-

Brookes, “Port Hamilton.” https.//www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1827 ↩

-

Brookes, “Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

Brookes, “Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

Lister, Hamilton Canada, 74. ↩

-

Brookes, “Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

Lister, Hamilton Canada, 23. ↩

-

Bill Freeman, Hamilton: A People’s History (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Limited 2000), 39. ↩

-

Brookes, “Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

“Made in Hamilton 19th Century Industrial Trail,” Library and Archives Canada, accessed January 10, 2022

https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/205/301/ic/cdc/industrial/19thcent.htm. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 5- Ericsson Wheels,1840,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1840. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 6- 1844-1847, 1844,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1844. ↩

-

Lister, Hamilton Canada, 75. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 7- Good Times in Port, 1847,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1847. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 7- Good Times in Port, 1847,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1848. ↩

-

Brookes, “Good Times in Port, 1847.” ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 7- Good Times in Port, 1849,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1849. ↩

-

Brookes, “Good Times in Port, 1849.” ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1852,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1852. ↩

-

Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1852.” ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1853,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1853; “Made in Hamilton 19th Century Industrial Trail”; “Old Port Hamilton.” ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1854,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1854. ↩

-

Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1854.” ↩

-

Figures 3-4 and Tables 1-2: Based off data from Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1854-1858, RG 43 Vol. 2403), 1854. ↩

-

Figures 5 and 6: Based off data from Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1854-1858, RG 43 Vol. 2403), 1854 but port locations are highlighted through the use of Google Maps. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1855,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1855. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 8- Boom Town Days, 1856,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1856. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 9- Depression Years, 1857,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1857. ↩

-

Ivan S. Brookes, “Chapter 11- 1867-1870, 1869,” in Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901 (The Estate of Ivan S. Brookes). https://www.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=Y1869. ↩

-

Brookes, “Chapter 11- 1869.” ↩

-

Brookes, “Chapter 11- 1869.” ↩

-

Brookes, “Chapter 11- 1869.” ↩

-

Figures 7-8 and Tables 3-4: Based off data from Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1875-1877, RG 43 Vol. 2406), 1875-1876 ↩

-

Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1875-1877, RG 43 Vol. 2406), 1875-1876 ↩

-

Welland Canal Register (Library and Archives of Canada, Vessel Registers Lock 3 1875-1877, RG 43 Vol. 2406), 1875-1876 ↩

-

Figure 9: “Bird’s eye view of the City of Hamilton: Province Ontario, Canada,” McMaster University’s Digital Archives, J.J. Stoner, 1876, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A70026. ↩

-

Figure 10: G.S. Rice (artist) and Endicott & Co. lithographer, “Hamilton, C.W.,” published by Rice & Duncan, 1859, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98508477/. ↩

-

“Sept. 29, 1847: Hamilton nickname ‘Ambitious City’ coined,” The Hamilton Spectator (September 23, 2016), https://www.thespec.com/news/hamilton-region/2016/09/23/sept-29-1847-hamilton-nickname-ambitious-city-coined.html. ↩