The Hammer

Hamilton Harbour's Steel Industry of World War II

Alexander Froude

Hamilton - 2022

Ten days after Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939, Canada declared war on the aggressive Nazi regime. This day marked the beginnings of the largest conflict in human history, but also marked the beginnings of one of Hamilton’s industrial booms. British authorities looked to Canada’s rich natural resources and industries to help bolster the Royal British Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy. One such industrial product was Canada’s steel. The city of Hamilton, located on the protected Burlington Bay on the most western shore of Lake Ontario, was the perfect choice for wartime steel contracts. Today, Hamilton is stereotypically referred to as Steeltown or as Hamilton musician Sonny Del Rio coined the city, “The Hammer,” which a fitting name for the industrial city whose steel boom of the 1940s changed Hamilton Harbour forever.1 Although the city was already an established industrial power by 1939, the production of wartime steel added many new facilities to its harbourfront and greatly expanded its industrial capabilities. Hamilton produced steel plating from its newly installed blast furnaces and rolling mills for ship production, it outfitted minesweepers and built barges on its harbourfront, and it produced a significant number of naval ordnances for wartime use. Although Hamilton’s companies were not prepared for such demand in production, the industrial demands of the Second World War forced them to improve their industrial capabilities which changed Hamilton Harbour forever.

Industrial Growth

Hamilton’s industry-filled shoreline was possible because of its irregular shape which provided the city with a much larger shoreline. Compared to Toronto’s straight shoreline, Hamilton Harbour had more space to build manufacturing facilities near the lake. Overtime, Hamilton’s shoreline extended northward, resulting in newly created inlets which were filled in with industrial waste by companies who subsequently built new facilities over the landfill.2 These new piers enabled industries to have access to deeper waters which would become vital in the new age of larger ships. By 1939, Hamilton’s industrial harbour was ready for large-scale production of steel for the war effort and the war brought many new facilities to Hamilton’s industrial sector near its harbour.

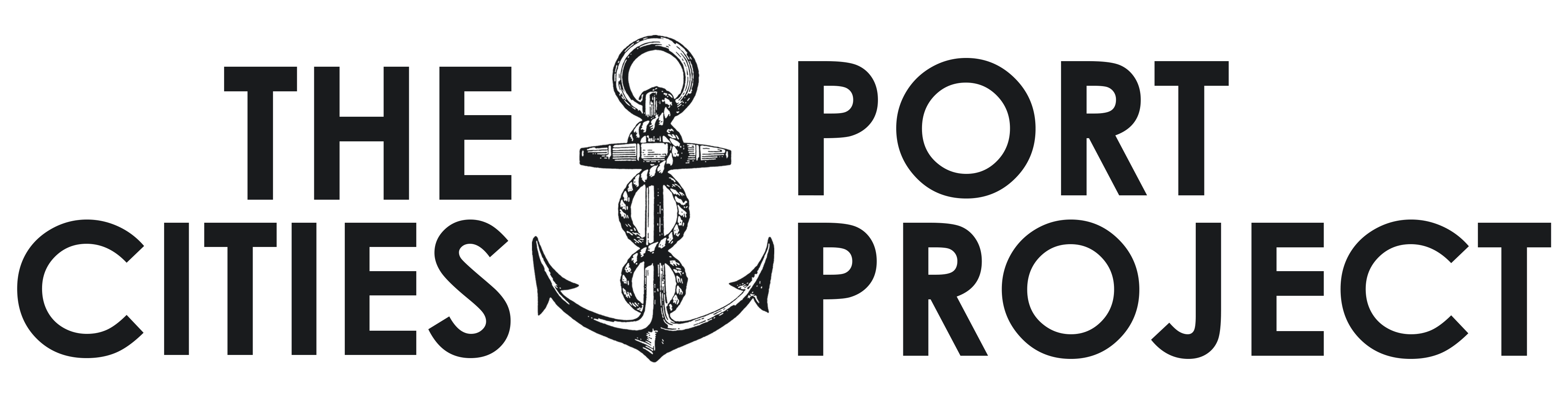

Figure 1: Insurance Plan of the City of Hamilton Sheet 230, showing the Steel Company of Canada, 1914.

At the outset of the Second World War, Canada did not have the capability to produce enough steel for the war’s heavy demand and relied on iron ore imports from Europe and the United States.3 With the war in Europe, Canada stopped relying on European steel and instead sought more steel imports from the United States. However, the United States had to abide by the rules of neutrality in the early years of the war which restricted exports for war use to only countries involved in the war.4 While Canada maintained a steady flow of steel from the United States for use on a North American basis, the country also relied on domestic steel manufacturers for the war effort.

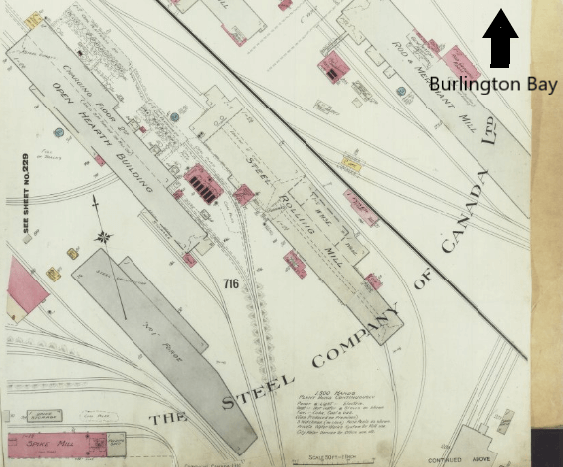

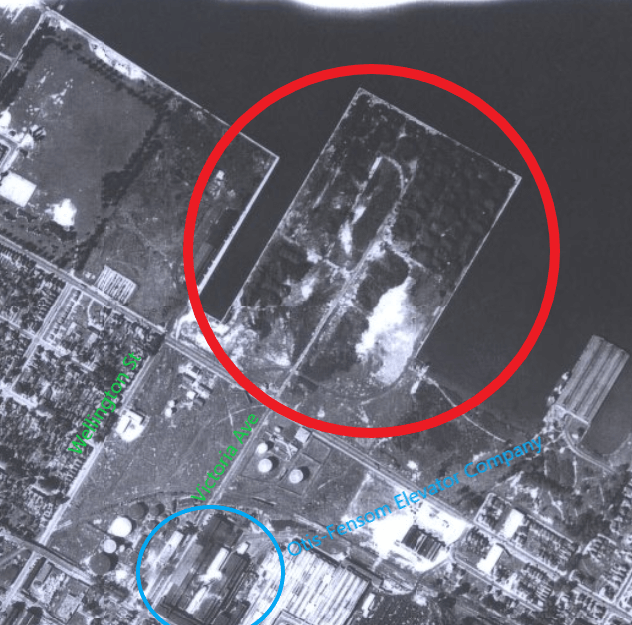

Figure 2: Greater Hamilton Area, from Caledonia to Vineland, 1934-11-03, showing Wellington Street Harbour in 1934 and featuring the Sawyer-Massey Company

Hamilton was home to experienced steel manufacturers and its harbour was ready to supply steel for the war effort. The Steel Company of Canada, which was based in Hamilton, emerged as the leading steel manufacturer in Canada after the First World War and accounted for 40% of domestic raw steel production.5 As the leading domestic steel manufacturer, the Steel Company of Canada used its own funds to purchase a $4.7 million steel mill that was capable of rolling 100 inch wide steel plates for the shipbuilding program in 1941.6 After this purchase, Hamilton’s steel manufacturing increased dramatically and its steel production was used in domestically built warships and merchant ships for the war effort.7

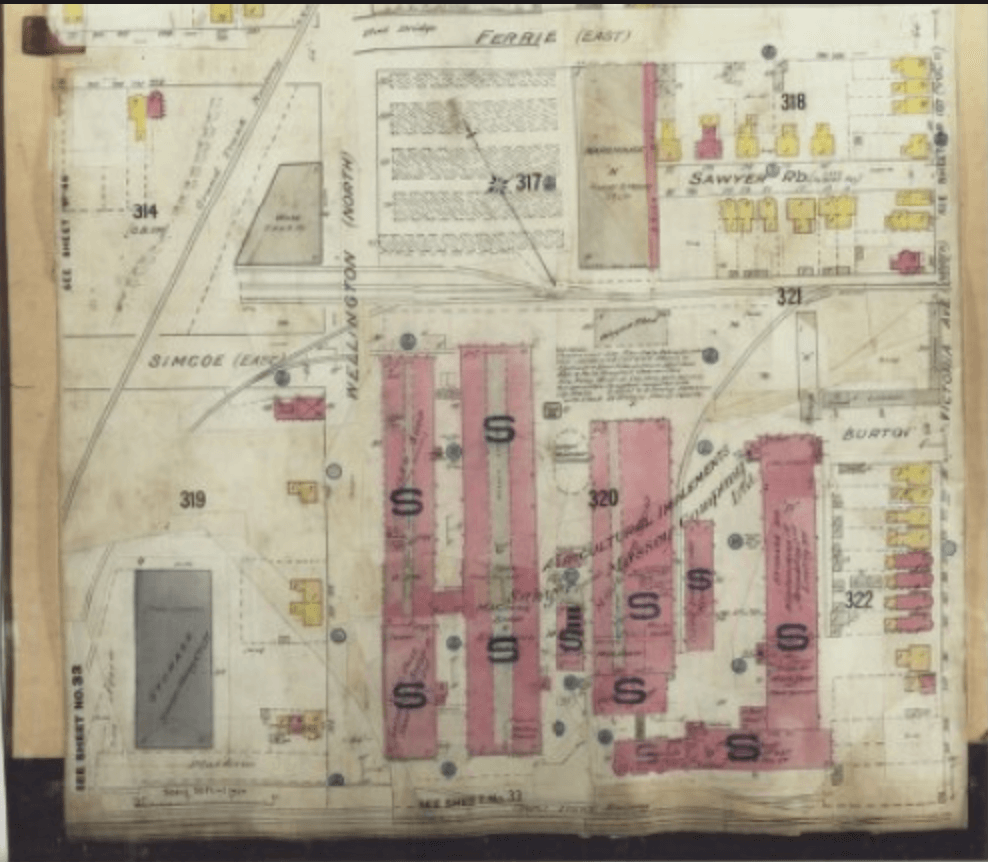

With the increase in steel production in 1941, new facilities had to be constructed to cope with the increasing demand. Hamilton Harbour was equipped for steel production prior to the war with companies such as the Steel Company of Canada already producing steel in the city (see Figure 1).8 The increasing steel demand during the Second World War changed Hamilton Harbour which led to the completion of new developments east of Wellington Street that directly aided in industrial production for the war effort.9 A new terminal dock was also added at the end of Wellington Street (see Figures 2 & 3) and significant modifications had been made to the harbourfront.10 These new modifications clearly demonstrated Hamilton Harbour’s willingness to improve its infrastructure to assist in the manufacturing of steel for the war effort.

Figure 3: City of Hamilton, 1943, showing Wellington Street Harbour in 1943 and featuring the Otis-Fensom Elevator Company

Further infrastructure was added in 1941 to help service the terminal dock such as railways and roadways.11 These new services brought the necessary materials in and out of the industrial sector and provided a connection between various industrial facilities. The docks between John Street and Catharine Street also received an extension, and services such as dredging and widening were completed in the Ottawa Street channel and the Steel Company of Canada’s channel.12 Dominion Foundries and Steel Company, Hamilton’s second largest steel producer in the 1940s, was not absent from the construction of additional facilities. The company contracted Frid Construction Company to build three additional extensions to its plant beginning in October of 1939.13

American Coal Imports and the Welland Canal

Coal was an essential product for steel manufacturing in Hamilton Harbour during the Second World War. After the coal was baked in coke ovens, it was used to fuel blast furnaces to turn iron ore into pig iron.14 The molten iron was then turned to steel using open hearth furnaces.15 Without the import of coal into the city, Hamilton’s wartime steel production would have never occurred. Hamilton was not located near any significant coal deposits, but through its intricate railway systems and waterways, it was more accessible to the coal fields within the United States than most steel-producing Canadian cities were.16 As steel production increased during the Second World War, the demand for American coal increased in tandem. Coal entered the city from coal-rich areas such as Pittsburgh and the Appalachian coal fields through the intricate railway systems.17 However, after the construction of the fourth Welland Canal in 1932, coal was brought directly to Hamilton Harbour by ship.18 While there were many American ports located on Lake Ontario, the “western end of Ontario (Toronto and Hamilton) and points along the Welland Canal [were] served from Lake Erie ports,” demonstrating the importance of the Welland Canal to the wider coal industry.19

The amount of coal being imported into Canadian ports through the Welland Canal increased dramatically because of the Second World War. In 1950, there was 4,835,363 tons of coal that travelled through the Welland Canal and entered Canadian ports compared to 874,720 tons in 1925.20 Located on Lake Erie, Toledo was the leading American port that exported coal to Canadian ports with a total of 5,226,252 tons imported to Canadian ports in 1950 compared to the second largest exporter, Ashtabula, at 2,195,130 tons.21 From Hamilton Harbour, coal was distributed to other ports along Lake Ontario and was transported out of Hamilton by railway. The city of Hamilton was located on two continental axes that provided service from Montreal to Western Canada by-way-of the Great Western Railway and provided service from New York to Chicago through the Hudson-Mohawk Valley.22 Thus, the rest of the Canadian and American Great Lakes region was serviced through Hamilton. With the increase in coal imports into Hamilton Harbour, infrastructural changes occurred to the harbourfront. Additional ships were built by Hamilton’s steel companies to unload raw materials, such as coal, that were increasingly being brought in by ship.23 With more coal arriving at Hamilton Harbour, its steel manufacturers were able to continue supplying steel for the war effort.

Politics of Steel and Shipbuilding Contracts

Hamilton’s steel production had been noted by many leading figures in the steel industry. The city hosted a convention of steel manufacturers in May of 1942. While on a tour of the plant of Dominion Foundries and Steel Company during this convention, Hamilton’s mayor, William Morrison, told members of the Association of Iron and Steel Engineers that “[they were] producing 55 per cent of the whole steel output of the Dominion [of Canada]” and also “producing and rolling all the plate used for corvettes and tanks.”24 This steel plate was ultimately made in Hamilton Harbour and was transported to Toronto Harbour to be used for the construction of wartime ships. The various ports along Lake Ontario subsequently worked in tandem to produce wartime vessels, which demonstrated the collectivity of the harbours of the Great Lakes.

Hamilton’s steel production was not the only industrial service that changed Hamilton Harbour’s infrastructure. The harbour converted many facilities for the outfitting of minesweepers and the production of barges. Hamilton’s controller, A. H. Frame, advocated for shipbuilding contracts for Hamilton Harbour and stated that Hamilton has “on the bay front several ideal locations for shipyards, and one, an abandoned boat slip, could be converted to this use at comparatively small cost.”25 However, ultimately no shipbuilding contracts were given to the city. Instead, Hamilton Harbour’s access to local steel opened the city for additional wartime tasks which would utilize the new slips in its harbourfront for the outfitting of minesweepers and the construction of barges. Toronto Harbour was contracted to build Algerine-class minesweepers for the British Navy in 1943, and with production deadlines that year, Hamilton took over the task of outfitting the minesweepers to relieve pressure from Toronto Harbour.26 The outfitting and manufacturing of Hamilton-made armaments took place on a seventeen-acre site at the end of Wellington Street where warehouses were utilised for storage and a machine shop was built.27 Hamilton Harbour’s outfitting yard was managed by Carter-Halls-Aldinger Company who oversaw the completion of Toronto-made hulls.28 The Hamilton Bridge Company was also contracted with the construction of Phoenix-type barges. The barges required a significant amount of steel and proper facilities for its construction process, which was the reason Hamilton was chosen for this task.29 These new harbourfront facilities were added to Hamilton Harbour’s industrial infrastructure and converted into normal production facilities for domestic use after the war.

Armaments and Munitions Manufacturing

Wartime steel demands were also driven in Hamilton by the need for armaments and munitions. This task was accepted by Hamilton Harbour whose industrial companies built and converted facilities for this challenge. The manufacturing of these products required steel, and so did the facilities built during the war to produce these products.30 Hamilton’s domestic steel production enabled a variety of corporations to produce armaments and ordnances for naval use during the Second World War. While Hamilton did not construct military ships for the war effort, the city continued to fit ships built at ports, such as Toronto, for service since all ships were required to be outfitted with armaments before departing for the Atlantic. Hamilton became the prime candidate for such a task and a project, overseen by the Department of Munitions and Supply for armament manufacturing and outfitting in Hamilton Harbour, began in 1943. Officials “were impressed with the many advantages the local port offered and other influencing factors were the availability of railway sidings for the shipment of materials and street car service for the large force of workers” that were completed east of Wellington Street in 1940.31 Thus, a seventeen-acre lot was reserved next to the Wellington Street slip to outfit the hulls of corvettes and Algerine-class minesweepers from various Lake Ontario shipbuilding ports.32 A variety of companies were tasked with the production of armaments and ordnances for the war effort. These companies left their regular production contracts and embarked on new tasks provided to them by the government.33

Figure 4: Insurance Plan of the City of Hamilton Sheet 047, showing the Sawyer-Massey Company, 1898

Sawyer-Massey was a manufacturing company based in Hamilton that built equipment for roadwork and agricultural use.34 This company had a long history in the city of Hamilton and was one of Canada’s leading manufacturers of agricultural implements at the turn of the 20th century.35 Its facilities, located north of the Grand Trunk Railway and east of Wellington Street (see Figure 4), were upgraded to enable them to construct a variety of naval armaments for the government.36 Sawyer-Massey was placed under a shared contract with Calgary-based Canadian Pacific Railway Ogden shop to build one thousand 12-pounder Mark IX mounts.37 In addition, the company was also contracted to build 546 four-inch single Mark XIII mounts designed for both Canadian and British frigates and corvettes.38

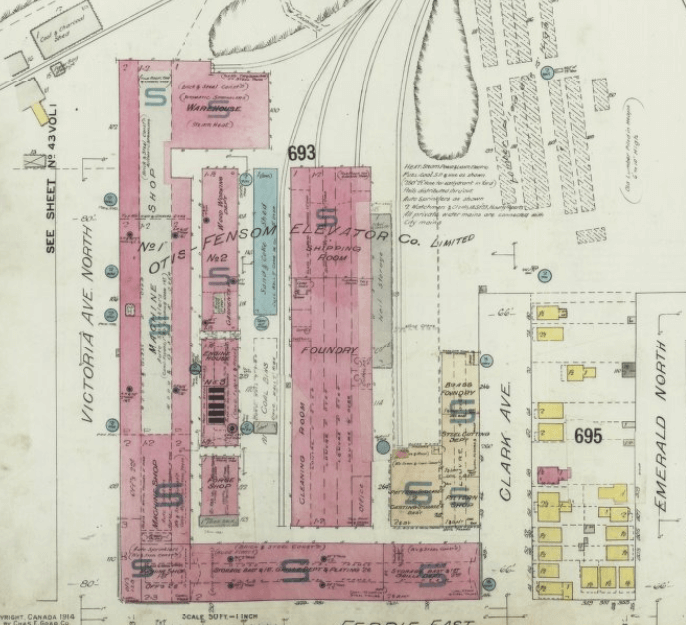

Another domestic company that received contracts to build armaments for the war effort was Hamilton-based Otis-Fensom Elevator Company. Like Sawyer-Massey, Otis-Fensom Elevator Company had to upgrade their facilities on Victoria Avenue to meet wartime production demands (see Figure 5).39 The company was involved in major developments to its facilities and harbourfront which was published in The Hamilton Spectator:

It was not to be expected that a company making elevators during peace-time could change overnight into a vast plant producing, in quantity, the Bofors 40 m.m. anti-aircraft gun and equipment. Involving not only tremendous plant expansion, the installation of hundreds of highly developed modern machines and the manufacture of an absolutely foreign mechanism consisting of some two thousand parts […] But in the creation of a new largescale project, [where] everything must be developed from the ground up [and] Buildings must be designed and built.40

Figure 5: Insurance Plan of the City of Hamilton Sheet 201, showing the Otis-Fensom Elevator Company, 1914

The construction of additional buildings for the manufacturing of Bofors anti-aircraft guns added to the infrastructure of Hamilton Harbour and its industrial sector. These armaments were mounted on the hulls of the unfinished corvettes and Algerine-class minesweepers in the Wellington Street slip. These new facilities were owned by the Dominion of Canada and after the war, the Studebaker Corporation purchased the new facility and became Hamilton’s first automaker.41 Thus, Hamilton Harbour’s new wartime facilities continued to benefit the city’s economy after the war.

End of the War and Hamilton’s Steel Future

While the end of the Second World War marked the greatest tragedy in human history, it marked the greatest opportunity for Hamilton Harbour. With its steel production, Hamilton Harbour saw the construction and conversion of many of its harbourfront facilities. The rise in steel production allowed the city’s industries to provide steel platting for naval use, the production and outfitting of minesweepers and barges, and the production of those armaments and ordnances. These new facilities, built during the Second World War, allowed Hamilton to compete with the growing demand of steel production in the post-war period which brought Hamilton into the sphere of major steel producing and manufacturing cities like Toronto. Hamilton Harbour produced industrial products at a value of $130,578,232 in 1939, equivalent to $2,665,261,415 in 2022.42 In 1943, its industrial products reached a value of $425,000,000, equivalent to $6,698,850,000 in 2022.43 By comparing the value of products produced in 1939 with its value in 1943, an increase of $294,421,768 is evident, which is equivalent to an increase of $4,640,675,907 in 2022. The industrial might of Hamilton Harbour during the war had changed its harbourfront infrastructure forever. “The Hammer” demonstrated its industrial prowess during the war and has been known for its production of steel ever since.

-

David Estok, “The origin of The Hammer a good mystery,” Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton, ON), June 9, 2007. ↩

-

Port of Hamilton, 1951 (Hamilton: The Hamilton Harbour Commissioners, 1951), 20. ↩

-

Chris Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” The Northern Mariner 16, no.1 (2006): 32, https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/114734/data?n=1. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 33. ↩

-

Peter Clancy, Micropolitics and Canadian Business: Paper, Steel, and the Airlines (Toronto: Broadview Press, 2004), 158. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 33. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 33. ↩

-

Figure 1: [Insurance plan of the city of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada]: [sheet] 230, photograph, McMaster University’s Digital Archive, March 1914, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A38927/-/collection. ↩

-

Port of Hamilton, 1951, 28. ↩

-

Figure 2: [Greater Hamilton Area, from Caledonia to Vineland, 1934-11-03]: [Flightline A4871-Photo 15], photograph, McMaster University’s Digital Archive, November 3, 1934, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A71866; Figure 3: [City of Hamilton, 1943]: [Flightline 747-Photo 13], photograph, McMaster University’s Digital Archive, 1943, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A72099. ↩

-

Port of Hamilton, 1951, 28. ↩

-

Port of Hamilton, 1951, 28. ↩

-

“Industry Here Feels Stimulus of War Orders,” Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton, ON), October 20, 1939. ↩

-

Clancy, Micropolitics and Canadian Business: Paper, Steel, and the Airlines, 151. ↩

-

Clancy, Micropolitics and Canadian Business: Paper, Steel, and the Airlines, 151. ↩

-

Peter Warrian, The Importance of Steel Manufacturing to Canada: A Research Study (Toronto: Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, 2010), 97. ↩

-

Bill Freeman, Glory Days: A Play and History of the ’46 Stelco Strike (Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2007), 6. ↩

-

Freeman, Glory Days, 6. ↩

-

Albert G. Ballert “The Great Lakes Coal Trade: Present and Future,” Economic Geography 29, no. 1, (1953): 54, https://www.jstor.org/stable/142130. ↩

-

Ballert, “The Great Lakes Coal Trade: Present and Future,” 53. ↩

-

Ballert, “The Great Lakes Coal Trade: Present and Future,” 50. ↩

-

Warrian, The Importance of Steel Manufacturing to Canada, 97. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 38. ↩

-

“U.S. Engineers Inspect Plant: Hamilton Mayor Tells of City's Steel Output,” The Globe and Mail (Toronto, ON), May 12, 1942. ↩

-

“Will Urge Shipbuilding Program for Hamilton,” Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton, ON), Apr. 12, 1941. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 39. ↩

-

“Ship Project Will Require More Storage,” The Globe and Mail (Toronto, ON), June 26, 1943, https://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/canadawar/munitions_e.html. ↩

-

James Pritchard, “Fifty-Six Minesweepers and the Toronto Shipbuilding Company during the Second World War,” The Northern Mariner 16 no 4, (2006): 44, https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/114736/data?n=1. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 42. ↩

-

Warrian, The Importance of Steel Manufacturing to Canada, 101. ↩

-

“Corvette and Algerine Types to be Brought Here for Equipping of Hulls,” Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton, ON), June 25, 1943, https://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/canadawar/hamilton_e.html. ↩

-

“Corvette and Algerine Types to be Brought Here for Equipping of Hulls.” ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 25. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 46. ↩

-

Canada Life Assurance Company. Hamilton, the Birmingham of Canada (Hamilton: Times Printing Company), 1892. ↩

-

Figure 4: [Insurance plan of the city of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada]: [sheet 047], photograph, McMaster University’s Digital Archive, January 1898, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A34222/-/collection. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 47. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 47. ↩

-

Figure 5: [Insurance plan of the city of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada]: [sheet] 201, photograph, McMaster University’s Digital Archive, March 1914. http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A34693/-/collection. ↩

-

“Otis-Fensom Plant Makes Great Strides, Passes Objectives,” Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton, ON), December 19, 1942, https://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/intro_e.html. ↩

-

Madsen, “Industrial Hamilton's Contribution to the Naval War,” 51. ↩

-

Vernon’s City of Hamilton Sixty-Sixth Annual Miscellaneous, Business, Alphabetical and Street Directory for the Year 1939 (Hamilton: Vernon Directories Limited, 1939), 8, https://archive.org/details/1939VernonsHamiltonCityDirectory/page/n7/mode/2up?q=dominion. ↩

-

Vernon’s City of Hamilton Seventieth Annual Miscellaneous, Business, Alphabetical and Street Directory for the Year 1943 (Hamilton: Vernon Directories Limited, 1943), 11, https://archive.org/details/1943VernonsHamiltonCityDirectory/mode/2up. ↩